The desert tends to turn folks nuts. What else could explain why, during our trip to Death Valley, my friend Shawnda and I address our rented Buick Rendezvous as Ron de Vous? Or why we have hers-and-his T-shirts made, reading hot and bothered respectively? Or why at the visitor center, I reach into a basket of plush toy birds and squeeze as many as I can, creating a riot of chirps?

Most people come to Death Valley for the extremes. It’s the lowest place in the Western Hemisphere (Badwater Basin is 282 feet below sea level), among the hottest spots on earth (summer highs often hit 120 degrees Fahrenheit), and unspeakably dry (annual rainfall averages 1.96 inches). They want to explore the desolate lake beds, the salt flats, and the rippling dunes, and learn about California’s early pioneers. They yearn to dangle from the derriere of a 20-foot-tall naked lady made entirely of cinder blocks. Then again, maybe that’s just us.

Day 1: Las Vegas to Furnace Creek

Death Valley isn’t all that deadly—in its recorded history, only slightly more than a hundred people have died there of anything other than old age. But it can be dangerous. Carry lots of water, and drink at least a gallon of it a day. Anyone who scoffs should read the visitor center’s pamphlet. There’s a harrowing story about a couple, Gerhard and Ingrid (so named, perhaps, because Germans love to visit Death Valley). On a hike, Gerhard dies of heat stroke. We think they’re fictional, but just the same, when was the last time you read of a death in a brochure?

For all that, the biggest cause of death these days isn’t heat stroke, rattlesnakes, mine hazards, or flash floods—all of which are risks. It’s single-car accidents. You imagine the roads to be flat and straight, but they dip and curve like crazy.

Our first stop is Dantes View (apostrophes seem to evaporate in Death Valley), atop a 5,475-foot peak in the Amargosa Range. Seven cars are in the lot; it’s the second-busiest place we visit on the trip. Most people consider Dantes the valley’s best panorama, and it’s pretty spectacular.

From there we drive to Twenty Mule Team Canyon, where the twisty, one-way dirt road is a good test to see if you feel comfortable on unpaved surfaces—they only get rougher elsewhere. We take far too many pictures of the lunarish hills. The next two days will prove them not to be the highlight we imagine.

Zabriskie Point is another of the park’s most famous views. The striated hills look oddly two-dimensional and wonderfully fake. This is where we learn the downside of drinking a gallon of water a day. The park’s bathrooms are usually holes, in sheds; we call them Crock-Pots, as the contents seem to be slow-cooking.

Even after just a few hours of barrenness, the oasis of Furnace Creek comes as a relief. There’s a lot to learn at the national park visitor center besides the birdcalls of local species. And if it’s wildflower season—March and April—you can pick up a flyer listing where flowers are being spotted.

Furnace Creek has three places to stay: the fancy Furnace Creek Inn, the mid-level Furnace Creek Ranch, and campgrounds. We’re at the Ranch, which could more accurately be called the Motel (Furnace Creek Ranch, Hwy. 190, 800/236-7916 or 760/786-2345, furnacecreekresort.com, cabins from $88). Our room is fine. Thank heavens I had signed up for the hotel’s e-mail newsletter. We were booked into one of the “cabins,” which are not actually cabins and are a third of the size of the standard motel-size “deluxe” rooms, but the newsletter listed deluxe rooms for the same $100 rate, so I upgraded us. The Ranch has a steak house, a diner, and a bar called the Corkscrew. A dip in the spring-fed pool, followed by a beer at the Corkscrew, and we feel rejuvenated.

Day 2: Badwater and Beyond

We start by taking Artists Drive, a one-way dirt road leading past Artists Palette, a hillside of many colors, including purple (from the manganese) and green (decomposing mica). If you squint it looks like spumoni. Afterward, we detour three miles down West Side Road, where the salt pan forms ridges in polygonal shapes. Heading back to Highway 178, we then stop at Devils Golf Course—it’s called that because the ground is jagged salt crystals as far as you can see. The crystals were left after an ancient salt lake dried up, and on a warm day you can reportedly hear the salt cracking as it expands.

Badwater is a couple of miles farther south. On one hand, it’s neat to be 282 feet below sea level. On the other hand, if there weren’t a sign on the cliff indicating where sea level is, who would know?

Twenty-seven miles later, we stop at the ruins of Ashford Mill, but they’re so ruined that there’s not much to admire. An Italian family pulls up—like a lot of visitors to the valley, they’re dressed in black. “Excuse me,” says the father, “but do you know which civilization built this?” He was clearly hoping for something more exotic than miners in the 1910s.

Beyond the park border, we have lunch on the patio at the Crowbar Cafe & Saloon in Shoshone (Hwy. 127, 760/852-4180, Ortega burger $6). The grizzled man at the next table drinks beer from a boot-shaped glass and is surprised to find a bug in it; really, that’s what you get for drinking out of a boot. Then a pigeon flies into the restaurant and walks across the grill, getting a hotfoot. The town is strange: Two doors down from this fairly rural establishment, Shawnda orders something called a mangolada with soy whipped cream at a coffeehouse named Café C’est Si Bon (760/852-4307, mangolada $4).

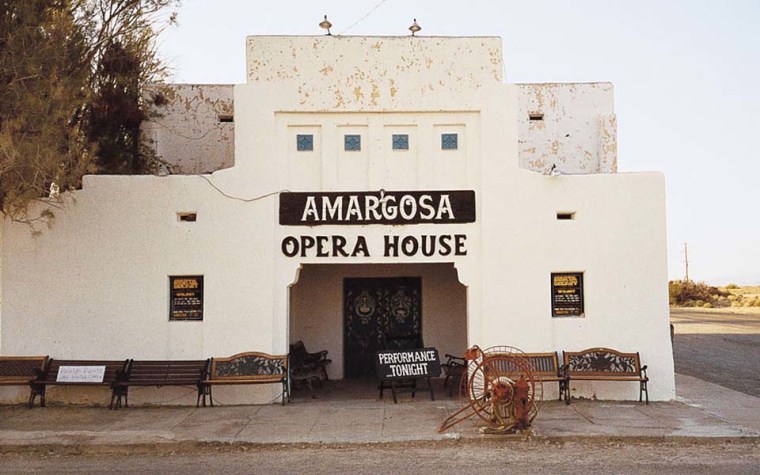

Death Valley Junction is a ghost town, or would be if Marta Becket would leave. A dancer, she visited the town in 1967 and stayed, buying the mining company’s social hall, renovating it, renaming it the Amargosa Opera House (Hwy. 127, Death Valley Junction, 760/852-4441, amargosaoperahouse.com, tickets $15, rooms from $49), and putting on a show for three nights a week (now one) for 36 years. Shawnda and I catch the performance on a later night. It’s a spectacle of endurance. Becket also owns the quirky hotel; rooms are $49.

I like a hike with a payoff, and Golden Canyon, just outside Furnace Creek, delivers. A quarter mile past the last explanatory sign you end up against the steep walls of Red Cathedral, glowing sacred in the late-afternoon sun.

We drive to the Furnace Creek Inn, have a drink at the bar, and stay there for dinner—tasty salads and a shared fig-and-prosciutto pizza. It’s a nice change of scenery that doesn’t cost a fortune.

Day 3: Western Loop

Mosaic Canyon, just west of the bump in the road that is Stovepipe Wells, has slick marble walls and narrow passages.

At times, the lines in the rock slant as much as 45 degrees, making the scenery appear tilted. Shawnda and I grew up near Disneyland, so perhaps that’s why we’re both reminded of its Splash Mountain ride.

The drive to Panamint Springs goes over a mountain pass, then twists down to a flat valley floor, where the road is as straight as George Will. We eat lunch at Panamint Springs (Hwy. 190,775/482-7680, burger $6)—like Stovepipe Wells, Panamint Springs isn’t a town so much as gas, food, and lodging. The mod, white plastic chairs would go for a mint at a big-city antiques store.

Heading back the way we came, we detour over to the Charcoal Kilns. Built in 1876 for making charcoal for smelters, they look like brick beehives, and you can walk inside them. It’s a little creepy, but not as creepy as Eureka Mine. We get three feet in before turning around. There are railroad tracks coming out of the mine, which only make us think of another Disney attraction, Thunder Mountain. Following the road (at one point along the edge of a cliff) to its end, we come to Aguereberry Point. It absolutely trumps Dantes View, with vistas on both sides of a promontory. Motorcyclists are coming up the dirt road—the National Park is very popular with people having a midlife crisis—so we head back to Stovepipe Wells.

Before checking into the motel, we stop at the dunes. As the sun drops, beautiful shadows form along the ridges. We commune with nature by doing banana rolls down the side of a big dune.

Even though Stovepipe Wells Village (Hwy. 190, 760/786-2387, stovepipewells.com, from $59)

is managed by Xanterra, the same company that runs the Furnace Creek Ranch, it’s grim. Our room stinks in a tangy, hard-to-pinpoint way, and we can’t switch because the place is sold out. The bathroom water isn’t drinkable; the noisy students next door are getting stoned outside. The restaurant is trying to be fancy (never a good idea in the desert), so, like the previous night, we eat at the bar—martinis, nachos, and chicken strips. It feels like a victory.

Day 4: Scottys Castle and the Racetrack

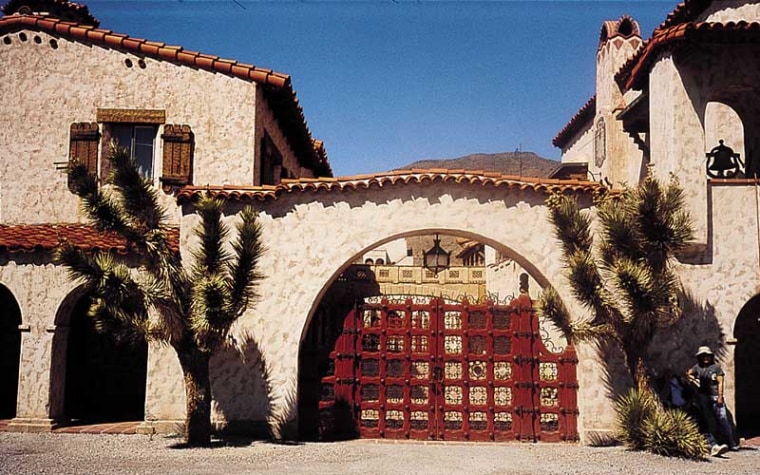

Walter Scott was a huckster who persuaded Chicago insurance magnate Albert Johnson to invest in mining ventures. After Johnson built a mansion in the desert, he let Scott claim to be its owner. Tours of Scottys Castle (760/786-2392, $9, kids $4) are led as if it were 1939. Our guide announces straight off that he’ll be playing the role of Michael Moody, who doesn’t like giving tours—a clever way of justifying his crankiness. The house is an epic folly, the tour entertaining.

Just to the southwest is 600-foot-deep Ubehebe Crater, created 3,000 years ago by a volcanic explosion. A sign in front of it shows a man falling dramatically down the side, which is not funny at all, no sir.

Far and away the highlight of Death Valley is the Racetrack, but I hesitate to mention it because (a) you have to drive for an hour on a rutted, unpaved road to get there, and (b) I don’t want to ruin it. Stones have fallen down the hillside onto a dry lake bed, and, inexplicably, they move, creating trails in the hard-packed dirt (no one has witnessed it). It’s mystical and fascinating and beyond comprehension. Even if there were no rocks, the lake bed—textured like cobblestones—would still be the best part of our trip.

We drag ourselves back to the car, driving all the way to the ghost town of Rhyolite, Nev. Shawnda gamely poses for silly photos in what was the red-light district.

At the adjacent Goldwell Open Air Museum (off Hwy. 374, near Rhyolite, Nev., 702/870-9946 (office in Las Vegas), goldwellmuseum.org, free), the surreal collection of sculptures, in a variety of styles, includes an eerie Last Supper as well as a rusty silhouette of a miner and his…penguin? We feel terrible for violating the cinder-block naked lady—Lady Desert: The Venus of Nevada, by Dr. Hugo Heyrman—but we have an excuse: The desert made us do it.

Finding your way

Because the points of interest are far apart, any Death Valley trip becomes a road trip. But there’s no real argument for moving from one motel to another. That would be the most efficient way to see most of Death Valley, but you could stay in any one place and do just fine (Motel 6 509 U.S. Rte. 95 North, Beatty, Nev., 775/553-9090, motel6.com, $44). Rental cars pose more of an issue (Death Valley National Park 760/786-3200, nps.gov/deva, weeklong pass for a car $10). Companies make you agree not to take the cars onto dirt roads, but some of the most interesting attractions require you to. None of the dirt roads mentioned in the story are outrageously rugged, but you absolutely need a four-wheel-drive vehicle with high clearance. (RV owners: Many roads prohibit vehicles over 25 feet.)

Day 1 Las Vegas to Furnace Creek, 175 miles Fly into Vegas, arriving before noon. Take Hwy. 95 north to Amargosa Valley. Go south on 373/127. At Death Valley Junction, turn right onto 190. Pay park entrance fee ($10 for one week). Past the booth, turn left on the road to Dantes View. Backtrack to 190. Twenty Mule Team Canyon and Zabriskie Point will be on the left. Continue on to Furnace Creek.

Day 2 Badwater and Beyond, 148 miles Take 178 out of Furnace Creek. Along this road are all sorts of attractions—simply follow the signs to Artists Drive, West Side Road (the salt flats are three miles down), Devils Golf Course, Badwater Basin, and Ashford Mill. Shoshone is 25 miles from Ashford Mill. From there, take 127 for 28 miles to Death Valley Junction, then 190 back to Furnace Creek. Turn left on 190 to Golden Canyon, then backtrack to Furnace Creek.

Day 3 Western Loop, 149 miles From Furnace Creek, take 190 north; the turnoff to Mosaic Canyon is just past Stovepipe Wells. Continue on 190 to Panamint Springs. After lunch, head back on 190 toward Stovepipe Wells, but turn right after a few miles onto Panamint Valley Road. After 15 miles, turn left, following signs to Charcoal Kilns. Backtrack to Wildrose campgrounds; just past it, turn right. Follow signs to Eureka Mine and Aguereberry Point. Turn around, follow Emigrant Canyon Road to 190, turn right. The sand dunes are past Stovepipe Wells. Backtrack to Stovepipe Wells Village.

Day 4 Scottys Castle and the Racetrack, 171 miles From Stovepipe Wells, take 190 east to 267; turn left. Follow signs to Scottys Castle and then back to Ubehebe Crater. The road to the Racetrack is past Ubehebe. Backtrack all the way to wherever you’re staying. One good option is Beatty, Nev. (Take 190 south to 374; turn left.) On the way is the ghost town of Rhyolite. In the morning, drive back to Vegas.

Resources

Road Guide to Death Valley National Park by Barbara and Robert Decker (Double Decker Press, $5.95.)