In the realm of the coin, market savvy is the coin of the realm.

The U.S. Mint is one of the few federal agencies that pays its own way, to a significant degree by listening to what its customers want. Collectors have made the state quarters among the most popular coins ever struck, spurring an interest in freshening up Americans’ pocket change. With two more new series of redesigned nickels on the way — commemorating the American Indians’ contribution to history — the cash registers are ringing.

They’ve got burrs that jingle, jangle, jingle

Burrs are the rough edges, still to be smoothed out, left when coins are struck. These days at the U.S. Mint, they’re the sharp, shiny talismans of profit.

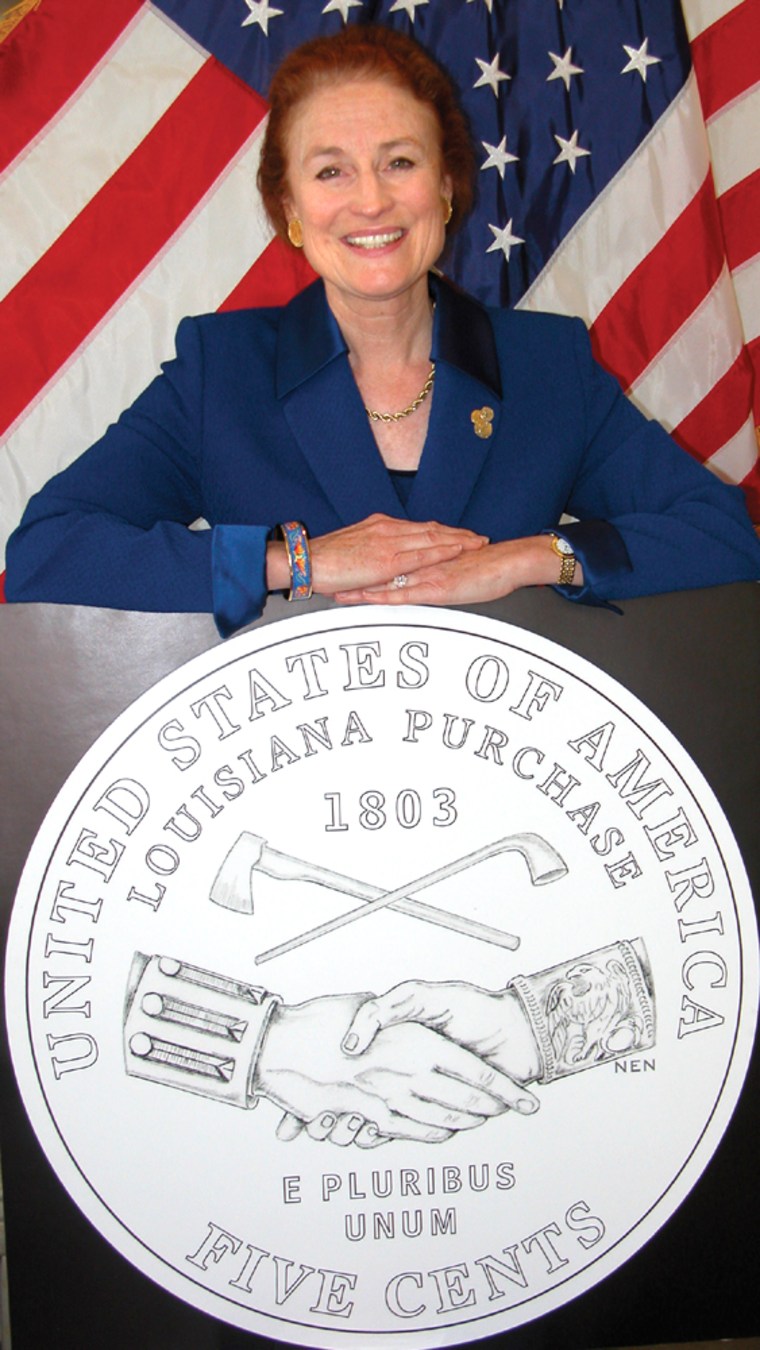

The turnaround at what once was one of the government’s more troubled agencies picked up steam in 2001 with the appointment of director Henrietta Holsman Fore. A prominent executive in the construction industry as head of Stockton Products, Fore was determined to impose private-sector business practices on the Mint.

Fore says she is a big believer in “businesslike government,” adding the agency is “really focusing on shortening our time to market, providing better value and reducing our costs so we can deliver value to the American people.”

More than ever before, the Mint aggressively markets its coin programs and seeks distribution channels by catering to collectors and ordinary Americans.

For example, said Michael White, a spokesman for the agency, the Mint is moving up the sale date next year of the annual proof set — a set of each of the coins in general circulation struck on special dies in near-perfect, polished condition. They will go on sale around March 9, three months earlier than before, so they will be on the market earlier in the year for people to give as gifts. A proof set of the five new state quarters will be out Jan. 6, five months earlier than before.

Plugging the nickel

Especially notable has been the rapid rise in redesigns for pocket change, whose look had largely been static for decades.

The two new nickels that came out this year bore the first new design in 66 years. The obverse — that’s the heads side — changed only a little, while the reverse (or tails), did a little urban redevelopment. Monticello was torn down, replaced by designs commemorating the Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

The next two sets, coming out next year, will look radically different. Thomas Jefferson will be freshened up on the obverse and pushed over to the side; for the first time, he will be gazing sternly off to the right, not the left.

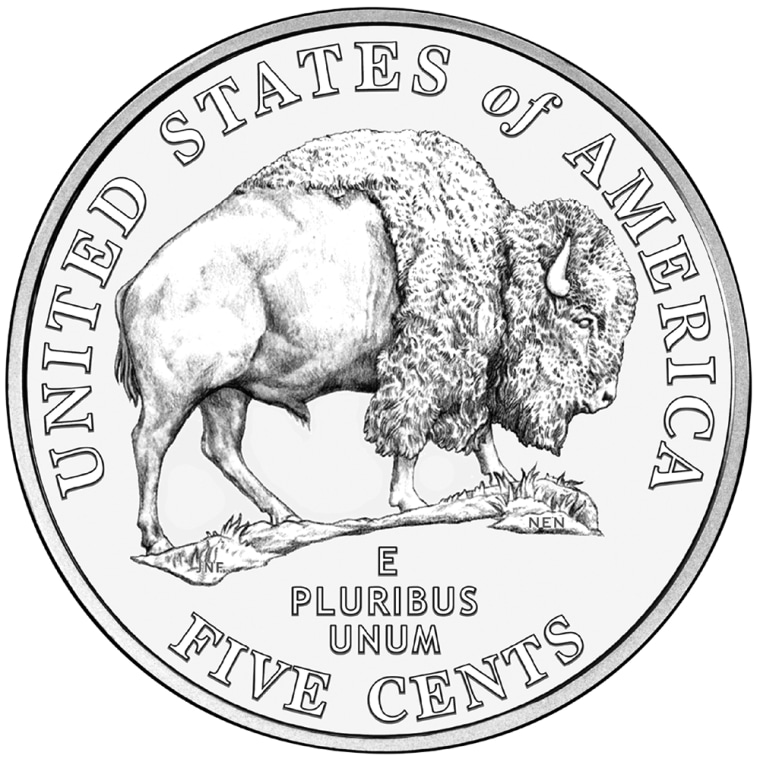

The tails side of the first new series, coming out this spring, will recall the stately bison that graced the highly popular “buffalo” nickel from 1913 to 1938. The second, which will follow in the fall, will depict the Pacific Ocean and the words “Ocean in view! O! The Joy!," which the Mint says reflect “an excited entry in the journal of Captain William Clark on November 7, 1805.”

The nickels have made a mint for the Mint: With the launch of the Westward Journey series, revenue from nickels rose from $37.2 million last fiscal year to $69.6 million in 2004, White said.

The nickels and other redesigned coins are especially attractive to collectors, and when it comes to collectors, the Mint hit a home run with its 10-year 50 State Quarters series.

Newly released figures from the Mint indicate that the quarters have made coin collectors out of as many as 140 million adults since the program started in 1999 — about one person for every household. As of last fiscal year — the latest for which complete figures are available — the Mint had made about $4 billion from them.

The quarters have been “the most successful coin program in United States history,” Fore said.

Balancing the books

The Mint sometimes likes to call those revenues a profit, but they aren’t, really. Still, they do make running the government cheaper.

The Mint does not distribute coins into the monetary system. That’s the job of the Federal Reserve, which has to buy them at full price.

Even though a quarter costs the Mint only about 6 cents to make, Fore said, the Fed buys it for 25 cents. The difference — called seigniorage (pronounced SEEN-your-ij) — goes straight into the general fund, where it substitutes for borrowing from the public and lowers the government’s interest costs.

It’s not really a profit because, in theory, it should all even out in the long run. Eventually, the excess is supposed to be spent down as the Mint redeems old coins and destroys them. But most old coins are never redeemed, thanks to collectors and forgetful spenders.

“Very few coins are turned in,” Fore said. “There is an attrition whether they are in washing machines or in dresser drawers or lost on the beach.”

Moreover, coins are “an interest-free loan to the government, a loan that never gets called,” John P. Mitchell, the Mint’s then-deputy director, testified before a House subcommittee in 2000. “Because coins generally last 30 years, the government gets to use the minted billions for a long time.”

The $500 million question

That’s one of the reasons the Mint has worked so hard, albeit with minimal success, to get the public to embrace a dollar coin.

The “golden dollar,” honoring Sacagawea, costs the Mint about 12 cents to make, representing seigniorage of 88 cents. Add that to the savings the Treasury would realize from eliminating the much-costlier dollar bill — which lasts only about a year and a half — and dollar coins would save the government as much as $500 million a year, according to a 2002 report from the General Accounting Office (since renamed the Government Accountability Office).

The problem is getting Americans to abandon the greenback, which won’t happen as long as the familiar $1 Treasury note remains in circulation. The Mint itself reported in 2001 that only about a third of the public would favor using a dollar coin in place of a bill.

“It’s difficult with tri-circulation,” Fore said, meaning the existence of three $1 currencies at the same time, counting the Susan B. Anthony dollar coin.

The answer, coin advocates insist, is to eliminate the dollar bill, a dramatic step Congress refused to take when it authorized the Anthony dollar in the 1970s and the Sacagawea dollar in 1997.

Resistance is stiff, and it’s not just from traditionalists who say the greenback is the most widely recognized symbol of America. Lobbyists for the paper and ink industries, for example, argued for keeping the dollar bill, as did the printers union at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

While “we would love to have more Americans receive [the golden dollars] in change,” Fore said, the Mint is agnostic on whether the dollar bill should stay or go.

“We know notes are easy to fold, light to carry, much easier on men’s billfolds,” she said. “So there are several varieties out there for the American public. [But] we will continue to try.”