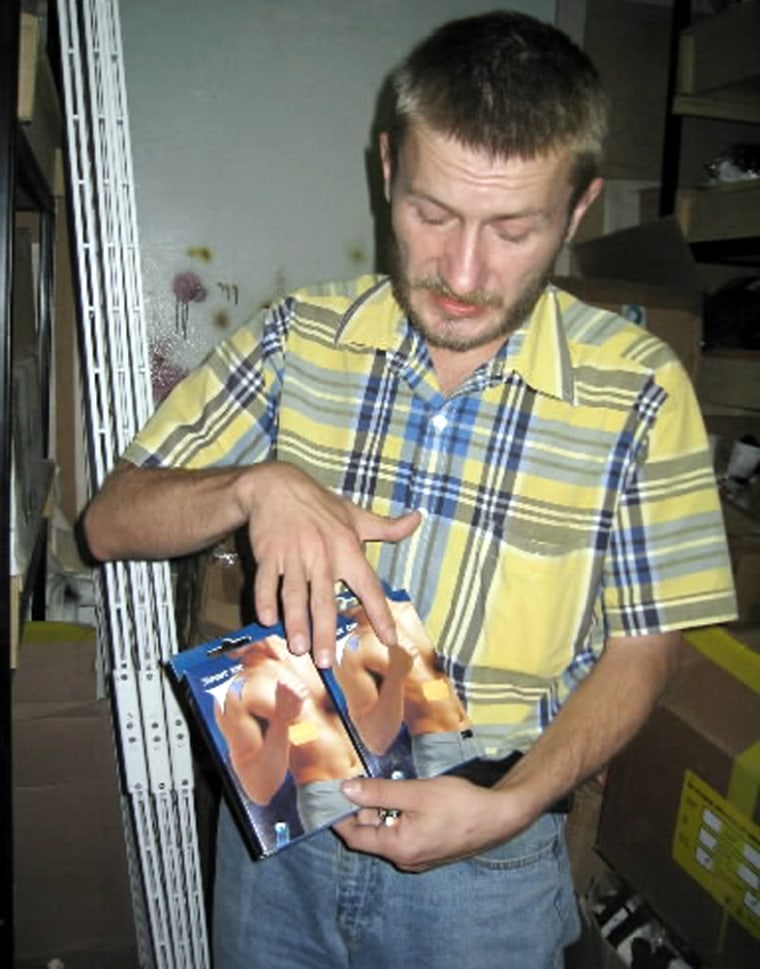

Alexander Markus shook his head as he looked at the two identical boxes of men's underwear.

This is his business now, and he has learned all too well the difference between briefs that will sell and those, such as the two Russian-made models he scrutinized in his storeroom, that won't. "Too expensive," he said. "Badly packaged." And he shrugged. It's "banal," he said, repeating a word he uses at least a dozen times a day, "but I have to eat."

Once, Markus studied advanced physics and was recruited to work at a top-secret Soviet nuclear research facility. Today, he is a reluctant capitalist in a country still uneasy about market forces unleashed by the fall of communism. "I'd give it up tomorrow — with pleasure," he said. "Business for business's sake never attracted me."

In the carnivorous world of Russian business, the banality of Markus's life represents a victory of sorts, a product of the tentative stability reigning in Russia under President Vladimir Putin. "Before, it was senseless to have property because you could lose it all," Markus said. "Now, there are some rules that sometimes even the authorities obey."

But his faith in the system — any system — disappeared along the raucous, violent, twisting path that preceded his quiet life as a trafficker in bras and bathing suits. Markus's trade-offs mirror his country's: In return for stability, Russians have given their president a free hand and have remained indifferent to the Kremlin intrigues that make this a time of uncertainty about the future of Russian commerce.

Markus's career, recounted over several days of interviews with him, his family, friends and associates, traces the arc of Russian capitalism. In the 1980s, he embraced free enterprise and flirted with being a dissident. In the 1990s, he learned the hard way about what he sardonically calls "Russian business" — armed mafiosi who seized his first store, crooked insiders who bankrupted the bank he worked with, Western companies that promised better but whose products were not what they seemed.

Only now, thanks to Polish panties and Turkish socks and the Putin era's relative prosperity, has Markus found a measure of economic security. At 38, he has built a chain of six stores in this industrial city on the Volga River. He employs 50 people, supports three children and plays computer games in the office because the work is not challenging for a man who planned to be a physicist.

"At last," he said, "I'm bored."

Fears of crony capitalism

Markus has long since given up on the democrats he once believed in and who now make him "feel like puking because they are just like everyone else." He says he believes the system is dominated by "parasite" bureaucrats and greedy oligarchs such as Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the jailed oil tycoon whose company, Yukos, is being carved up by the state as part of Putin's drive to concentrate power in the Kremlin.

Markus is among millions of Putin voters ready to accept a more authoritarian system as the price of a more predictable life. Yet he is not an unconditional believer in the promises of Putin's Russia.

As he drove through Nizhny Novgorod's cratered streets, Markus nodded at a new mall anchored by a vast Turkish superstore. "We haven't yet faced these giants. That's why we can live," he said. Soon enough, he explained, he would have to expand his business to match the competition. But Markus fears becoming what he disdains — a capitalist like Khodorkovsky, making money by "stepping on the bones of my neighbors," and vulnerable to state manipulation, or worse.

So Markus remains a skeptic, his skepticism earned at the barrel of a gun. "Rich experience in this country tells me real stability will be achieved only after death," he said. And he wasn't really joking.

No rules, big risks

"I don't want to spit at the mirror in the morning," Markus said, arguing good-naturedly with his best friend Valera Nakaryakov, back for a visit after emigrating nearly a decade ago.

Nakaryakov was eager to blame Russia's "wild capitalism," for the many reverses Markus has suffered. He had considered taking the same route. "I had to make a conscious decision: either work in business here or leave," he said. "I left." Today, Nakaryakov is a British citizen, a prominent young space physicist at the University of Warwick who lists 58 scholarly publications on his résumé. He consults for NASA and the European Space Agency and his latest findings are the subject of glowing press releases.

Over a beer near the classrooms where they were once inseparable, Nakaryakov told his friend that he would always see him as an unwilling capitalist.

"You were forced to work in business," he said. "You did it against your will."

Actually, it was politics — Markus's one and only flirtation with it — that set him on the path to becoming an underwear salesman.

The year was 1989, and the young physicist known as Sasha to his friends was one month short of finishing college. He and Nakaryakov — both married with young daughters — had prestigious jobs lined up at Arzamas-16, the nearby secret nuclear facility. But Nizhny Novgorod, at the time still a closed defense industry city called Gorky, seethed with activists hoping to emulate the nuclear scientist-turned-dissident Andrei Sakharov, who spent much of the 1980s in exile here. "We were all democrats then," Markus recalled.

"Everything was falling apart," Markus said. "I wanted to feel like a dissident and help break it down completely." That May Day, he joined protesters at the annual labor parade shouting pro-democracy slogans. The police detained them. "The whole crowd was happy, we were all singing revolutionary songs. Even in jail we were happy," he said.

Sympathetic professors couldn't hush up the scandal of the arrest. Not only was Markus not allowed to graduate, but Nakaryakov and other friends also lost their promised jobs at Arzamas-16. "Among the group a black sheep was found, so they decided not to let anyone go," Markus said.

'Easy come, easy go'

He was uncertain what to do next until a friend "gave me a tip that there's this word called 'business' " and hooked him up with a group buying computers at low prices in Moscow and selling them at high prices in Nizhny. Markus became technical director because he "at least had seen a computer before." The money was great. "Any business then was super-successful," he recalled. "There were no rules of the game in the new market — or in the new country — and the attitude was 'easy come, easy go.' "

Never a joiner, Markus decided to strike out on his own as a trader. "I was just learning," he said. "Later I realized it doesn't matter what you trade, as long you don't trade people, drugs and weapons."

But it was disorienting. He was flush with unaccustomed money and surrounded by questionable new friends from the world of gray commerce. His marriage fell apart in 1991 as the Soviet Union dissolved. "He got into business and that's how he started drowning," said his first wife, Anna Marinichenko. "People started getting money they had not seen before; it was a party time. Many Russian men got broken at that time."

By then, Nizhny Novgorod's name had been restored and city fathers imagined a trading future for the town based on its history as the commercial crossroads of the Volga and the Oka rivers.

Markus opened a modest general store on Gorky Street. But bandits soon preyed on owners like him, demanding protection money to serve as the store's krysha, or "roof." Markus slept at home with a new wife and a hunting rifle. One night in 1993, gunmen burst into his apartment and demanded he give them his store. "They put a gun to my wife, so of course I gave them the store," he said.

When he went begging for his store back, a gangster made him a different offer, asking Markus to work with his bank. He accepted and learned from the inside about the so-called banks that proliferated in the 1990s, serving as private money caches and laundering operations for a few well-connected insiders.

Ostensibly, he was there to check on borrowers' collateral. "But it turned out nobody needed it. All these banks gave credit exclusively on the principle of friendship or direct orders from the owners," Markus recalled. In 1995, the bank imploded in what he called an "artificial bankruptcy."

He found work at a large agricultural firm selling fruit, and immediately hated it. His second wife left him. After the bank disaster, "both the bandits and the police were chasing me," he recalled. The police found him first, and he spent a month in jail until convincing them he was just a witness, not a participant, in the bank's crimes.

Crisis and opportunity

It was then that Markus turned for the first time to the world of socks, stockings and underwear, setting up several small stores. He found a supplier in Moscow that imported cheap Turkish goods. But business wasn't great. In 1997, Markus's partners cut him loose and he found himself liable for $10,000 in debt.

Threatening envoys arrived, demanding money. Markus had no way to pay and, as he said wryly, "they couldn't do anything except kill me, and if they killed me they wouldn't get anything."

At one point, the Moscow firm sent an imposing athlete named Oleg Gavryuchenkov "to make an impression on me." Gavryuchenkov, who said he owed his formidable physique to years of water polo, declined to discuss his first encounter with Markus. Asked what business he had been in during those days, he said with a modest smile, "People who had problems trading — we solved these problems."

At first, Markus tried to raise cash by working for a French firm that sold food supplements. But even this company, he found, cut corners. Despite the long list of ingredients advertised in the supplements, "most weren't really in the product," he said.

After three months, he gave up and went to Moscow to pay his debt by working directly for the company. It was the spring of 1998.

"I became a slave," he said.

The Russian economy crashed that August. The supplement business, along with tens of thousands of others, was ruined when a ruble devaluation made the cost of imported goods inaccessibly expensive. In the crisis, though, Markus saw opportunity. He had decided that Gavryuchenkov, the beefy enforcer, was a decent sort, and the two took a proposal to the firm's management. They would sell off the company's stock of products at the massive wholesale market on the grounds of Moscow's Luzhniki Stadium.

And so that fall, Markus learned what it was to rise at 4 a.m. for a hard day's labor as they unloaded the remnants of the company. Even after all he had been through, the brutal laws of the market were a revelation. "Luzhniki is a place you can make $2,000 or $3,000 a day — and lose $5,000 or $10,000," he marveled. "It's not a very human way of life."

By late 1998, Markus had acquired just enough money and Turkish socks to return home and start a new business. The first link of what would become his modest chain was a rented corner in a food store. There was room only for one stand of socks. But Markus gave the enterprise a grand name: "European Tricotage."

After everything that had come before, selling underwear was hardly the worst thing that had happened to Markus. "It was a pleasure," he said, "to bring a bit of beauty to people."

Cautious optimism

Markus was inspecting "Number One," his first store on Freedom Square. It was the height of the swimsuit season, and two sales assistants were occupied with customers as he glanced at the neat racks of knockoff T-shirts printed conspicuously with brand names such as Nike, Polo, Donna Karan and Dolce & Gabbana.

"Everybody knows what these are and we don't try to hide it," he said. "Real brands are completely inaccessible to the people who shop in our stores."

Each year for the last five, Markus's business has grown. "Number One" has always been his best-performing shop; turnover now is up to more than $20,000 a month. Gangsters no longer come demanding money. "The last offer from a krysha came four years ago. We refused with great pleasure," Markus said. European Tricotage is now a well-known name, and he's expanded into wholesale. He recently made his first foreign business trip to Turkey.

Pressured by clients eager to "normalize" business, Markus even decided to open a company bank account a year ago — a huge leap after years of operating on an all-cash basis.

But Markus today is still just a member of what the head of the Russian small business association calls the "commercial proletariat." He is visibly stressed, a bearded wraith whose clothes flop off his thin frame. He rarely eats during the day, subsisting on coffee and cigarettes. He owns no car or mobile telephone. His modest apartment, where he lives with his third wife, her 10-year-old daughter and his 12-year-old, costs just $300 a month.

The dream of a capitalist model city on the Volga has long since dissipated; Nizhny Novgorod today is no longer even in the top 10 regions for foreign investment. Average purchases at Markus's stores are just $7. Markus's sales assistants, working on commission, take home as little as $100 a month during slow periods.

The smothering hand of the bureaucrats, or chinovniki in Russian, is a constant problem. "Mr. Chinovnik is like a parasite on people like me," he said. Usually, he deputizes his brother Maksim, a construction engineer by profession, to handle headaches such as the $85 fine they tried to contest for having the incorrect time on their cash register. "We got the fine and said, 'We won't pay, you sue us,' " Maksim recalled. "But the tax inspectors said, 'No, you sue us.' To sue your tax inspector, well, it is bad for the future. We understood that."

"For 1,500 years," he said, "the government has been blaming us just for living in Russia."

And yet at times Markus is cautiously optimistic, contemplating plans to open a warehouse in Moscow and expand his wholesale trade. "We're just starting the process in which people think about tomorrow," he said. "For 10 years, it was very hard to plan anything. We had such a struggle. But now, I would like to make some forecasts."

He sees his small underwear empire as a refuge from the rest of Russia, where he works surrounded by a small circle of trusted friends, such as brother Maksim, childhood playmate Dima and cousin Sergei. He has no intention of getting involved in politics, business groups or civic action of any sort.

"Like many of my generation, I separated myself from the state long ago and I'm living in the worlds I like more," he said. "Any person involved in small business builds his own state himself."