WASHINGTON — It’s August, a hot summer is winding down, and out in the Western U.S. water has become a big concern. The flow and levels in the Colorado River have become so low that last week the federal government announced a Tier 2a water shortage, which requires Arizona, Nevada and Mexico to reduce their use of water from the river by 7% to 21% in 2023.

But the bigger story is the long-term impact out West, where agricultural needs and growing populations are bumping into a decadeslong drought — and where it feels like large-scale changes are coming.

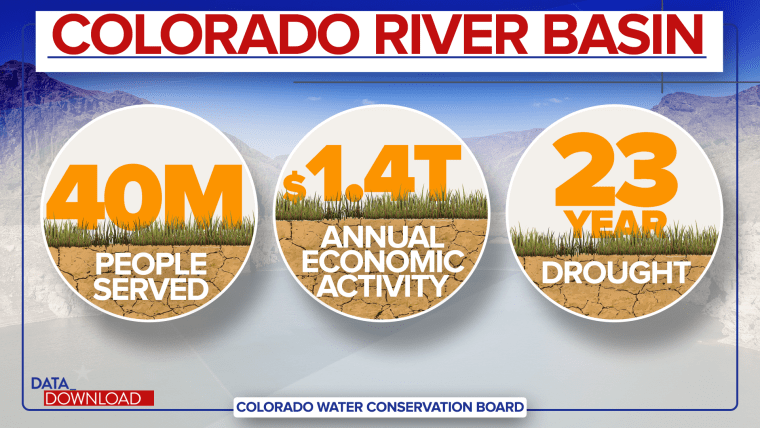

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the Colorado River Basin in the Southwest.

Water from the river and its tributaries serve roughly 40 million people in Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. It supports $1.4 trillion in annual economic activity — agriculture and other commerce.

And the area is going through a 23-year drought as dry as any period in the last 1,200 years.

The impacts can be seen across the region, where dry riverbeds mark the landscape and formerly productive farmland sits unplanted because of inadequate irrigation. The size of the problem is apparent at Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the massive reservoirs designed to capture the flow of the Colorado. The human-made lakes are key to the survival of the region, and if their water levels get too low, they won’t be able to generate electricity for homes and businesses.

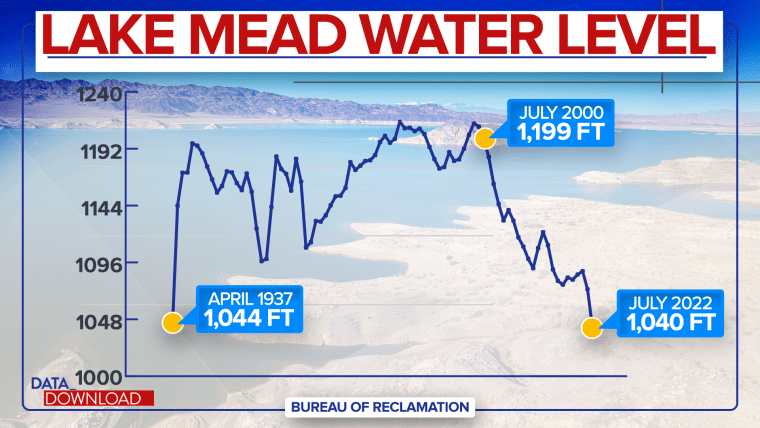

How low are the lakes? Consider Lake Mead, on the border of Arizona and Nevada.

The lake’s level is down by about 160 feet from where it was in 2000. And its July elevation of 1,040 feet was the lowest it had been since April 1937. That’s when the reservoir was still being filled up. If the lake gets to an elevation of 950 feet, the dam will no longer be able to produce hydroelectric power.

The story is just as dire at Lake Powell, on the Arizona-Utah border. It sits at an elevation of about 3,533 feet. The lake needs to be at a minimum of 3,490 feet to be able to generate power.

There are a lot of drivers in these numbers. On top of the drought, the warmer weather of recent years leads to more evaporation. It’s also hard to ignore the impact of growing population. The seven states fed by Colorado River Basin are all growing, and many are adding people faster than the national average.

The area is also home to some big and fast-growing metro areas, including Albuquerque, New Mexico; Denver; Las Vegas; Los Angeles; Phoenix; Salt Lake City; San Diego; and Tucson, Arizona, which all draw water from the Colorado River Basin.

As a group, the counties that hold those cities grew a little faster than the national average, 7.6% versus 7.4%. But the big impact is in the overall population numbers. By 2020, those counties had 1.6 million more people than they did in 2010.

That’s a lot more faucets, showers and spigots tapping a limited supply of water that has been hit by a drought, and its effects are likely to extend beyond watering lawns or filling pools.

For instance, most of the water from the basin — an estimated 70% — goes to agriculture. When it’s winter in the North, a lot of the produce at your local supermarket comes from farms in the Southwest. And as water becomes scarcer, it’s going to become more difficult to farm in the area. That means less farmland, fewer farms and possibly higher prices for produce.

Furthermore, there’s no reason to expect those cities are going to suddenly stop growing. They are likely to add more population in the next decade, and that would only add to the challenges in the area.

If the population growth in those counties over the past decade continues for the next 10 years, the problem only deepens.

By 2030, those counties would have 1.9 million more people drawing off the water that comes from the Colorado River Basin.

That’s an estimate, of course. No one can say for sure how the populations will grow and change, but, considering the state of the basin, any additional growth will create new pressures on an already overtaxed system.

Last week’s action by the federal government shows the pressures are already building. And, climate change skeptics aside, the trend lines on water and population in the area suggest we are only at the beginning of a set of long, hard discussions in the Southwest — and in Washington, where decisions about resources will be made.