More than three decades after a serial killer began preying upon gay and bisexual men at bars in New York City, the victims and their families, as well as the activists who fought to bring the elusive murderer to justice, are the subjects of a four-part docuseries that premieres Sunday on HBO and Max.

Directed by Anthony Caronna and based on Elon Green’s award-winning 2021 book, “Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York,” the true-crime series revisits the yearslong search for Richard W. Rogers Jr., a former surgical nurse at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital who was convicted of killing and dismembering two men in 1992 and 1993 — and suspected of killing others. He was sentenced to life in prison in 2006.

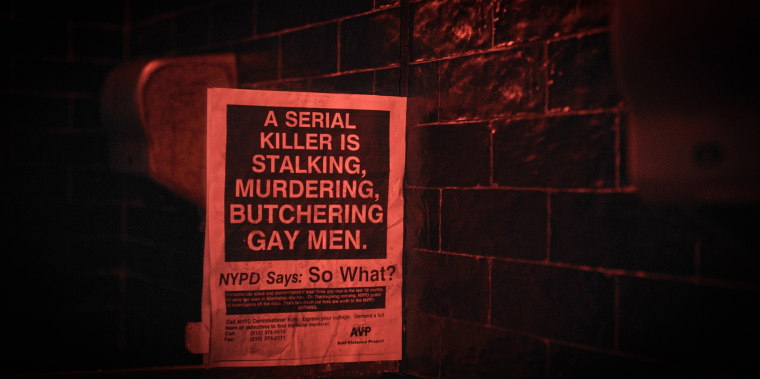

Using archival footage and first-time interviews with investigators, prosecutors, family members and activists, “Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York” aims to humanize the victims while spotlighting the efforts of community leaders and organizations, such as the city’s Anti-Violence Project, which fought for fair treatment of LGBTQ crime victims.

“Being able to tell the story in a documentary format would allow us to get to the heart of the nature of anti-queer violence and also the response to anti-queer violence,” executive producer Howard Gertler said in a joint interview with Caronna. “It seemed like an opportunity to tell a historical story that has resonance both in terms of where this violence comes from and how to respond to it, at a time when we need to hear it most.”

In 2020, Caronna, whose directing credits include the feature film “Susanne Bartsch: On Top” and the FX docuseries “Pride,” was given an opportunity to read Green’s manuscript about the search for the “Last Call Killer,” but he initially passed on the project, citing a lack of interest in the true-crime genre and a fear of revictimizing the victims and the families. But it wasn’t until a year later, when Caronna met with Gertler, that he began to see the potential for a larger conversation about the history of violence against the LGBTQ community.

After they got the green light at HBO in early 2022, Caronna and Gertler worked closely with Nikita Shepherd, a Columbia University graduate student whose areas of focus include LGBTQ history. Shepherd guided the producers through the major people and events in the second half of the 20th century that shaped public attitudes toward LGBTQ people, including the AIDS epidemic.

“Nikita would take us through people like Anita Bryant, through the early 1970s, ’80s, and say, ‘This is where this backlash sort of came from and started,’” Caronna said.

Gertler, best known for producing the Oscar-nominated documentaries “How to Survive a Plague” and “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed,” said the work of the show was to go beyond the “who, what, where and when” laid out in Green's book and to examine the “how” and the “why” behind the killings and the protracted police investigation.

“You can’t understand the ‘how’ or the ‘why’ without understanding and illuminating the historical context,” he said.

In November 2005, Rogers was found guilty in a New Jersey court in the stabbing deaths of Thomas Mulcahy, a 57-year-old computer salesman who was visiting New York City on business in July 1992, and Anthony Marrero, a 44-year-old Puerto Rican sex worker who was last seen in May 1993. Although he was never convicted because of a lack of evidence, Rogers is also suspected of having killed at least two others: Peter S. Anderson, a 54-year-old Philadelphia investment broker whose dismembered remains were found in Pennsylvania in May 1991, and Michael Sakara, a 55-year-old typesetter whose remains were found in New York in July 1993.

The docuseries even delves into Rogers’ run-ins with the law before the 1990s. In 1973, while he was attending the University of Maine as a graduate student, he stood trial in the murder of his roommate, Frederick Spencer, with a hammer. He claimed self-defense and was acquitted. In August 1988, a 47-year-old Manhattan man told police that Rogers had drugged and attacked him. Rogers was acquitted in a nonjury trial a few months later.

By leading their own investigation into the victims with sensitivity, the creative team wanted to “peel back the onion of homophobia” by creating the familiar feeling of most true-crime documentaries — and then adding a queer twist, Caronna said.

"By the time we get to 1973, I hope we set it up enough so that the audience goes, ‘Oh, my God, this is just another example of extreme homophobia that allowed these murders to keep happening,’” he said.

Gertler said one of the big themes of “Last Call” is “the way that institutionalized homophobia and transphobia works, and that was one of the most horrifying things [they discovered] when we were doing our own digging and reporting into the circumstances around the 1973 murder and trial and the 1988 assault and trial.”

“This is someone who should never have been out on the streets: 15 months after his second acquittal, he killed his first victim," Gertler said. "So, unfortunately, to understand how that poison operates, you have to explain it, show it and include it in the show to understand the forces that were sort of arrayed against justice in this case.”

Following the controversial success of Ryan Murphy’s “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story,” which received backlash from the families of Dahmer’s victims after it debuted on Netflix in September, “Last Call” arrives in a true-crime boom in both scripted and unscripted programming.

Confronted with the ethical dilemma of not wanting to retraumatize the people who lived through that era while not pulling any punches in their reporting, the producers said they felt it was important to be upfront about their intentions and to let their subjects control the flow of the interviews, especially because many of them have seldom sat down to discuss their advocacy work or their memories of their loved ones.

Gertler singled out a dinner scene with the Marrero family at the end of the second episode, in which older, more conservative family members are trying to figure out how to talk about Anthony with two younger and openly queer relatives, as an example of the constructive conversations that can come out of revisiting this dark period of LGBTQ history.

“Something I’m really proud of is that every single person who sat down with us came away having had a really cathartic experience, really glad that they had participated,” he said.

“I think historically, the position that queer people are in today, we’ve been here before as a group, and we’ve figured out strategies of resistance and change-making,” he added. “So I think it’s important for us to be able to feel like we can call on those same strategies today to understand that community and creating community is one of our greatest strengths, and using that community to resist and make change is one of those great strengths, as well.”

Caronna said HBO’s reach is able to bring in an audience that may not be aware of the history of anti-LGBTQ violence in the U.S.

“I think the power of true crime is that it is something that is clearly very loved by a lot of people and a genre that people enjoy watching,” he said, “so I’m hoping that we were able to use the genre as this Trojan horse of sorts to get people in to watch this riveting story but also along the way pick up something that they had no idea about.”