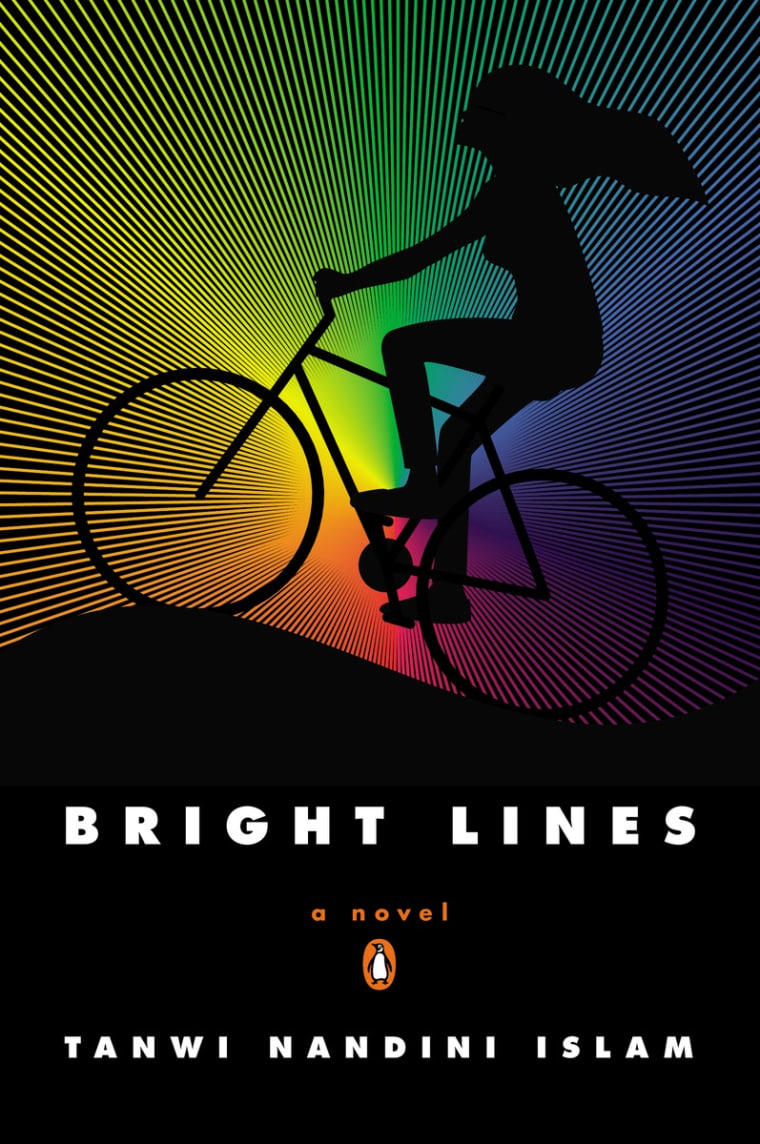

A middle-aged pot-smoking apothecary owner; his 18-year-old aspiring hijab fashion designer daughter Charu; his adopted 20-year old daughter/niece Ella who is haunted by the untimely death of her biological parents; and Maya, the daughter of a local Islamic cleric, Charu’s friend and Ella’s love interest. These are the main protagonists in Bright Lines, Bangladeshi-American writer Tanwi Nandini Islam’s debut novel, which is released today.

Bright Lines goes beyond the tired cliché of South Asian characters juxtaposed against their white counterparts. The novel’s South Asian characters, set in 2004 Brooklyn which some time traveling to 1971 Bangladesh, are surrounded by other communities of color and interact with them on a daily basis on the busy streets of New York. The characters in the book also represent Brooklyn’s diversity, in terms of race, class and gender identity with a major focus on queer South Asian protagonists.

Islam, herself, grew up all over the American South and Midwest until her parents finally settled in upstate New York when she was ten years old. However, she always felt much more at home when she visited her family in Queens. But it was really when she moved to Brooklyn in 2004 that she became intimate with New York City’s Bangladeshi community. Islam also took numerous trips to Bangladesh during the almost decade-long process of writing Bright Lines, to explore the history and people of the 44-year-old nation.

Bright Lines also inspired Islam’s own apothecary line, Hi Wildflower Botanica. She is currently working on her second novel, The Rivers. Her non-fiction writing has appeared in Elle.com, Fashionista.com, Gawker and more.

In an email interview with NBC News, Islam shares more about Bright Lines.

What are some of the messages behind Bright Lines? What do you want your readers to get from your novel?

Bright Lines is an exploration of family, coming-of-age, sexuality, faith and place for a pretty invisible group in the South Asian canon but a highly visible group in New York City: Bangladeshis. This is a character-driven book, and about diasporic identities across race, gender, class and sexuality. There are rich, loving friendships among people of color. Muslim has a myriad of meanings, all of them complex. There is a lot of wish-fulfillment in this book, and there are tragic moments. But realism doesn't have to solely mean pain and death for women, queer and trans people— there is joy, too.

What inspired you to write about a family-run apothecary in Brooklyn?

I love the innumerable hustles of Bangladeshi immigrants in New York City. So many entrepreneurs of all stripes, and among my favorite interactions would be with the shop owners on Atlantic Avenue. I was addicted to Egyptian Musk and Sandalwood oils, the kind you see sold on the street, and they were the ones who'd bring people from all walks of life together. I wanted to create spaces that celebrated that type of entrepreneurship, and banded together diverse groups of people.

Whatever work I had, every night and weekend was spent working on the book.

How long did it take to write Bright Lines?

Nine years total. I started the prototype of the novel in 2006, when I was living in New Delhi. On a little holiday to Kashmir, I remember being in a weird fever dream state and writing the first chapter that would eventually get me into Brooklyn College's MFA program. I wanted to buy time to really work on the book. After two years of working on disparate chapters, I completed a draft while living in the French Riviera, during 12-hour shifts selling shawls to rich Europeans. Whatever work I had, every night and weekend was spent working on the book. By 2010, barely a year out of my MFA program, I found my agent Rebecca Friedman, and we got the novel in shape to send to publishers. I remember we sent the book out on her birthday, the leap day - and a month later, the novel was sold.

Writing and entrepreneurship – not common career paths for Desis [people of South Asian descent]. Is your family supportive of your career choices? Did they ever steer you towards anything else?

No, my parents couldn't steer me if they tried, and they half-heartedly did try when I was in college, but I was adamant. Ever since I majored in Women's Studies [at Vassar College], I think they got the hint. I've always been rebellious and resentful of any sort of indoctrination. That means that my style, my spirituality and my work have been out of bounds for most of my adult life. My parents' unwavering support has meant that my work may flourish or flounder, but without their judgment. Mostly they want me to thrive and be honest at whatever I choose. Entrepreneurship is definitely something I attribute to Desi communities, however. You get in where you can fit in to survive and often that means making your own way. There's no life of guaranteed material wealth when you choose writing or small business, but I've had some vivid experiences which lends itself to what I want to do. My folks and I always joke, if you want an interesting kid, you have to be prepared to deal with the times they let you down, too.

There are so few known Bangladeshi-American authors. They're often lost in the mix between Indian and Pakistani literature. Who are some writers/artists you have been influenced by?

Whenever there's a new Bangladeshi woman author, I make sure to read their work. By virtue of the Internet, I've been super lucky to become close friends with poet Tarfia Faizullah, whose poem Dhaka Nocturne is one of the epigraphs in my novel. My friend Fariba Salma Alam is a Bangladeshi-American artist whose multimedia works explore the same terrain as I do in visual language. These women are fiery, wayward and irreverent - that is the spirit of our work.

What advice do you have for budding writers, especially those from communities of color?

What sets our hearts alight when we read fiction is not only seeing ourselves in a story, but reading something we've never read before. And I think artists and writers of color have these beautiful, oft-hidden stories that need to be recorded. Our stories are necessary: this can be our guiding principle as we show up to the page each day. It can help push us along. While we need time with each other, in communion, we also need our solitude and time to be in our own messy thoughts. We're too connected these days, much more so than when I first started writing. We all need time to disengage from our desires and projected social media lives, in order to create the work that only we can make.