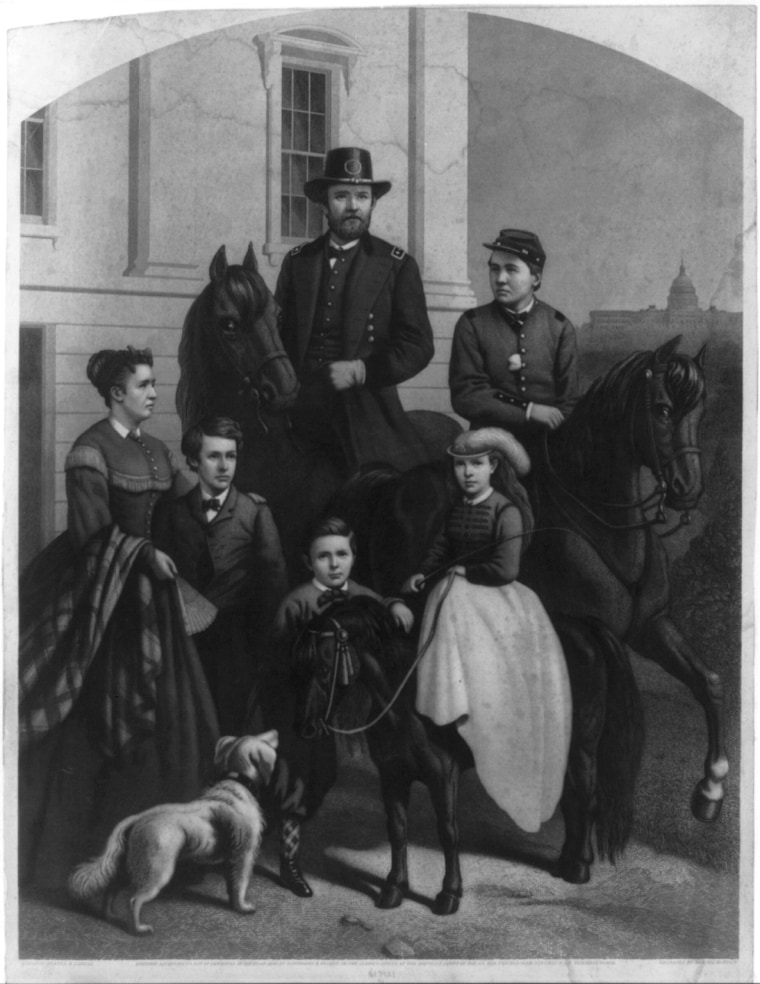

President’s Day is often described as a day of remembrance, a holiday when everyday Americans could reimagine themselves inside the Oval Office and look back at the country’s most pivotal political moments through the eyes of the president of the United States. So we sat down with bestselling and award-winning presidential biographer Ronald C. White to discuss one of America’s most influential presidents — Ulysses S. Grant — whose passion to defend African-American and Native American rights was partially inspired by his close relationship with Mexico.

Grant was one of America’s greatest generals—a master battlefield commander later elected in 1868 as the second Republican president. History buffs might compare Grant with another general-turned-commander-in-chief—President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Both Republican leaders graduated at the middle to bottom of their West Point classes (Grant was 22nd out of 39 and Eisenhower was 61st out of 164), but each rose through military ranks to become Civil War and World War II heroes respectively.

White says that Grant’s story is important because it challenges Americans to think about the paradoxes that shape our politics and policies.

“One of the hidden stories is the way Grant is willing to use the central government to stand squarely on the side of African-Americans,” White told NBC Latino. “Here is the irony, the Republican Party becomes the party of the central government. Now they’re the party of states rights. And the Democratic Party then was the party of states rights. Now they’re the party of strong central government.”

Both then and now, America was a very divided country. And Grant had the heavy responsibility of rebuilding and reunifying. White describes in his 2016 biography “American Ulysses” how Grant defended equal rights for all Americans — first, by using the power of the federal government to support African-American voter rights against white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan; and then becoming the first president to take a moral stance in favor of Native Americans.

Many readers today, however, might be surprised to discover that the seeds for Grant’s civil and human rights commitments were planted early on in his military career during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), which ended with Mexico losing approximately one-third of its territory — including most of California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico — to the United States.

“He called the Mexican-American War our ‘most evil war,’” White said, describing how Grant opposed political ambitions that aimed to expand the U.S. border across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. “He said he should have resigned. For Grant, the very idea that a large country could attack a smaller country was the most immoral venture the United States had ever embarked upon. And that’s why after the Civil War, all the way to the end of his life, Grant would visit Mexico, had friends in Mexico, and admired Mexico’s struggle to become a liberal democracy.”

White says that Grant learned early on that the real value of a leader depends on his or her ability to empathize with other people, understand their point of view. And “American Ulysses” presents evidence documenting this perspective. In a letter to his wife Julia — while stationed in Fort Vancouver after the Mexican-American War — Grant denounces how Native Americans were being mistreated by white settlers: “My opinion [is] that the whole race would be harmless and peaceable if they were not put upon by the whites.”

For Latinos today, Grant’s empathy is just as compelling because not only did it influence the president’s policies when it came to passing the Civil Rights Acts of 1870 and 1875 — which guaranteed equal rights to African-Americans — it guided the development of a Native American peace policy that called for greater integration; but it also strengthened his commitment to keeping Latin America free from colonial empires and to abolishing slavery in the hemisphere.

Grant supporters say that the president’s failed annexation of Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) in 1870 — defeated by the U.S. Senate — aimed to compel Brazil, Puerto Rico and Cuba to end slavery. But critics argue that the annexation policy also fed into American expansionism, which was later championed by political forces that supported the annexation of other territories like Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam from Spain, as well as Hawaii, and continues to shape American foreign policy, sometimes transforming the world into a battleground for isolationist and interventionist ideals.

Others also criticize Grant’s Native American peace policy, which failed to protect the Great Sioux Reservation in South Dakota from thousands of white settlers entering the territory to mine for gold. This escalated into the Black Hills War (1876). And some people today compare the political tensions that led to the bloody conflict with the ongoing Standing Rock protests in North Dakota — where Native Americans are fighting to block a government-backed pipeline that could put their clean water and ancient burial grounds at risk.

But in spite of these contradictions, Grant’s story has the power to remind readers that to fully understand the history of America you need to see the country through a double-sided mirror that reflects opposing sides — Native American and settler, colonial and colonizer, slave and slave owner, native-born and immigrant. And this capacity to see oneself through another person’s eyes, White says, defined Grant’s character.