One in 4 teachers report being told by school officials or district leaders to limit their classroom conversations about race, racism or bias, a new survey shows, even as research published this week illustrates the potential benefits of learning about the historical and political roots of racial inequality.

The nationally representative survey, which pulled from responses from nearly 2,400 K-12 teachers and about 1,500 principals, was released Wednesday and conducted by the Rand Corp., a nonpartisan think tank.

Nearly one-third of educators reported being told to limit their classroom discussions in more than a dozen states with state-level restrictions on classroom conversations about racism, sexism and other contentious topics.

One in 4 social studies and English teachers and 1 in 4 principals say they’ve been harassed about policies on race, racism or bias.

The data provides one of the first comprehensive looks at how efforts to restrict classroom conversations about race in many states and districts have affected educators and school administrators.

“It’s heartbreaking for our youth, who won’t be getting the high-caliber education that they could be getting from a multimedia, multicultural, global era,” said Tony Diaz, the writer, activist and professor who started the Librotraficante movement a decade ago, “smuggling” forbidden Chicano history and other books from Texas into Arizona to defy a ban on Mexican American studies in the state.

Diaz, who's a professor of English at Houston Community College, said the numbers reflected in the teacher survey show the “damage” that "censorship campaigns” have done to the morale of educators everywhere.

The survey found that over half (54%) of all teachers and principals oppose legal limits on classroom conversations about racism, sexism and other controversial topics. The opposition to limits on these topics was higher for teachers and principals of color, at 59% and 62%, respectively.

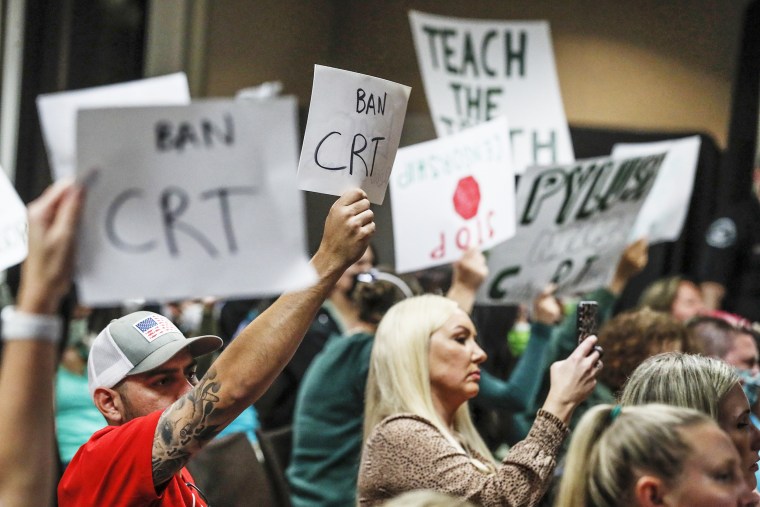

The Rand survey said teachers raised concerns they weren't being allowed to include more diverse perspectives in their curriculum and struggled to square their lesson plans with districtwide and statewide policies on critical race theory.

“I have had parents come in and say, ‘If this is what you’re going to teach, my student doesn’t need to know about this,’" an unnamed teacher said in the report.

There may also be greater agreement among educators in urban areas than elsewhere about the existence of systemic racism, the survey shows. Three quarters of teachers and principals in urban areas believe it exists, compared to roughly half of their rural counterparts.

Understanding inequality's roots

The findings come on the heels of new research published in the academic journal “Politics, Groups, and Identities” on Monday providing evidence of the effectiveness of teaching about the historical roots of racial inequality. The 22-page report analyzed data from across two studies, including a survey experiment in which adults were randomly assigned to learn about the effects of housing and economic policies that have contributed to modern racial inequality.

Learning about racial inequality among Black and white Americans increased the proportion of white participants who believed it exists.

Overall, the researchers found that “emphasizing the historical and structural roots of contemporary racial inequalities” can increase beliefs in its structural causes, especially among white Republicans and independents, as well as reduce “racial resentment” among political groups.

Steven White, an assistant professor of political science at Syracuse University and one of the report’s authors, said the findings suggest encountering historical arguments has the potential to “push attitudes in a more egalitarian direction, at least at the margins.”

Measures opposed to critical race theory or anti-racist education and training have been passed at either the federal, state or local level in every state except Delaware, according to the UCLA School of Law’s CRT Forward Tracking Project. The tracker shows 100% of “anti-CRT measures” at the local school board level in Colorado and Rhode Island have been successfully enacted.

“Teachers are disheartened by these things because they know how important it is for students of color and queer students and Muslim students to see themselves represented,” said Bettina Love, co-founder of the Abolitionist Teaching Network and an education professor at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

From May to late June, anti-CRT measures in the database increased to 480, up 28%.

“How do you recruit teachers in this climate?” Love said.