QUINCY, Wash. — Decades ago, it was a rarity to spot a Black face among the hundreds of white concertgoers at a Dave Matthews Band, Phish or Grateful Dead show. Now it’s common to see a sprinkling of Black people at these jam band events. Little Black kids sport band T-shirts and Black couples pull up to venues in cars covered in band decals and bumper stickers. They’re right at home.

“I like dancing to the music and screaming my lungs out!” said Isis Christmas, 12, who celebrated her ninth Dave Matthews Band concert with her family over the weekend. Her sister, Amethyst, 15, shouted a familiar greeting for DMB fans at this famous venue: “May the Gorge be with you!”

It was the last show of DMB’s annual three-night stint at the The Gorge Amphitheatre in Washington. Isis, Amethyst and their siblings excitedly carried their lawn chairs and snacks to a grassy area to enjoy the concert. Jermaine Christmas said it wasn’t hard to get his little ones into the band he’s loved for about three years. He said his girlfriend, Chila Oglesby, who is half white and half Black/Creole, introduced him to the group and going to the shows has become a family event.

“It’s just a great family setting, it’s great to be out here making memories for the kids,” said Christmas, 49. “There’s no, ‘Oh this isn’t Black music, this is white music.’ It’s just everybody’s music. That’s what I love about coming out here. Everybody’s out here from whatever color, age, race. From my first time to now, I see more Black people starting to come.”

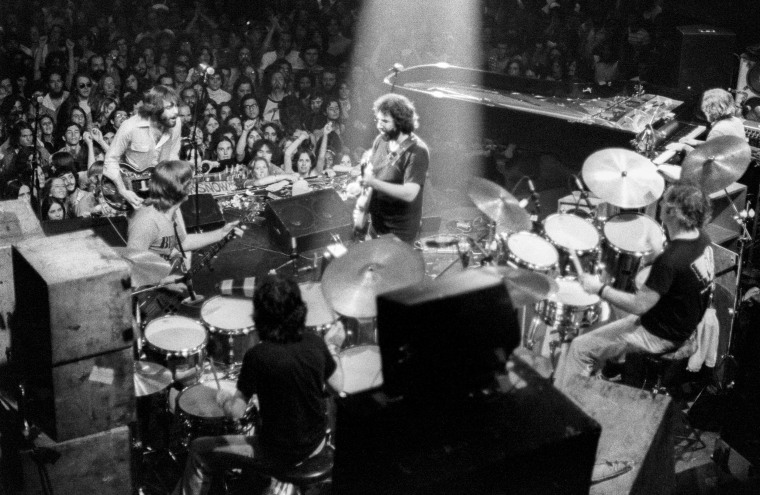

These jam bands are known for their dedicated, cult-like followings, with loyal fans traveling from show to show during tour seasons, eager to attend as many concerts as possible. They admittedly have a reputation for playing quintessential “white people music” for crowds of rowdy hippies. But, according to many Black jam band lovers, a deeper look at the music reveals a celebration of genres created and championed by Black people, like funk, jazz and blues.

Whether it’s with family or friends, Black fans have carved out important spaces for themselves within these crowds and fostered community amid the overwhelmingly white jam band fandoms.

Malcolm Howard, a longtime Phish fan, said he often meets with a group of Black friends from New Jersey for shows, and they make a point of traveling for concerts, since he lives in Florida now. “I have a big multicultural crew,” Howard adds, noting that he also attends with other people of color. He even introduced his mother to the band in 2021, taking her along to join in the music he’s loved for so long.

“Now she understands what her son’s been doing all these years. And she loved it. It was amazing,” he said. “As a Black person being in a majority white space, to understand that you have a place, that it’s your song too, that’s very important to me.”

The popularity of jam bands in an era seemingly dominated by stadium-filling artists like Taylor Swift and Beyoncé leaves some scratching their heads. But ticket and album sales are a testament to the loyalty of their fan bases. DMB, Phish and Grateful Dead are among the top touring artists of the past 40 years, according to Pollstar, which collects data on the global concert industry. Out of a list of 150 artists, DMB came in at the second largest ticket-seller, Grateful Dead at 10th and Phish at 12th.

“We only have like 35,000 fans, and they just go to every show,” Matthews told iHeart Radio in 2018. He was half-joking, but there’s truth to his words. It’s easy to find people at DMB concerts celebrating their 50th, 100th or even 500th show.

The same can be said for Phish fans. Howard said he attended his first Phish show in high school and has been to hundreds since, attending every one of their concerts for the past five years. The Grateful Dead’s final five concerts, celebrating 50 years and marking the last tour for the group’s core members, raked in $52 million in ticket sales in 2015, with more than 360,000 people attending at least one of the shows, according to Forbes.

There was no chance Lenny Duncan would miss the Grateful Dead’s farewell shows in California. He took his daughter and then-wife with him. “It was cool to see them enjoy the scene that I was part of for so long,” he said. “It felt like passing on the torch. My daughter became a big Dead and Company fan after that.” (Dead and Company, the Grateful Dead’s spinoff band, wrapped its final tour over the summer.)

Duncan has been a “Deadhead” since his teen years, when he left home and was living on the streets. He met a group of people following Jerry Garcia — the original Grateful Dead lead who died in 1995 — and slipped into the jam band lifestyle. His love for the group was wrapped up in the community he desperately needed at the time.

“I was able to live as a part of a collective, I was able to live on someone’s bus for a while. I was able to sell T-shirts rather than end up in the foster care system. It’s been 30 years now of me going to jam band shows,” he said.

Duncan is the author of “Psalms of My People: A Story of Black Liberation as Told Through Hip-Hop” and co-host of Blackberry Jams, a podcast that explores the intersection of jam bands and Black liberation efforts. He recalled traveling to shows with a group of five other Black people, and they’d make up a majority of the Black fans at Grateful Dead shows. Today, he’s a big Phish fan and frequents concerts for lesser-known jam bands like Goose and Eggy.

Jam bands, named for their emphasis on improvisation, blending genres and lengthy jam sessions, extend far beyond DMB, Grateful Dead and Phish. But the three have become synonymous with the art form, and their fan bases credited with developing the carefree, festival-like culture. Both Duncan and Howard say Black people have just as much a place in this culture as any white fan does, but they acknowledge that their inclusion hasn’t come without some micro-aggressions.

“If you’re a Black fan of a jam band, the question you always get is ‘So, is this your first show?’” Duncan said. “If it’s not that, it’s ‘Have you seen them a lot?’ Just this amazement that a Black person knows the same music as them.”

Howard agreed, adding that, for a long time, some Black people likely didn’t feel comfortable attending jam band shows.

“I would say a lot of it’s the legacy of segregation in general in public spaces,” Howard said, noting that he enjoys seeing more Black people at Phish shows. “I think those walls over time are going to come down.”

In 2018, Howard and fellow Phish fan Adam Lioz founded Phans for Racial Equity, a nonprofit organization aimed at combating discrimination and racism in the live music scene. The group travels to jam band shows, setting up tables and talking to concertgoers about fostering an inclusive, antiracist environment at the events.

A majority of the dozen jam band fans who spoke to NBC News said a white person — usually a friend or romantic partner — introduced them to the music. “It is lonely sometimes and you have to justify having this passion for the music,” said Chassie Sherretz, 43, who has seen DMB at the Gorge nearly every year since 2016. Sherretz began bringing her daughter to the shows, much like the fans who end up bringing their own friends and relatives into the fandom.

Larry Smith, 55, said his wife, Kelly, who is white, introduced him to the Dave Matthews Band in the 1990s, and he’s been hooked ever since. At one of the group’s recent shows at the Gorge, Smith sported a pair of shorts and a button-down shirt with Dave Matthews’ face printed all over the outfit. He topped off the look with a massive chain featuring the band’s fire dancer logo.

“I used to be the only Black person in the crowd. We’re starting to see more and more Black people,” Smith said, noting that he recently attended a show where he saw about 50 other Black people, “which I’ve never seen before. Whole Black families!”

“We meet each other, then we start recognizing each other, so there’s starting to be a little group that travels around.”

For fans like Kira Fluker, a 31-year-old “Deadhead,” she said she’s managed to find her Grateful Dead community online. “I’ve had a lot of younger kids on TikTok find me because they’re into the same kind of stuff,” she said. “They find me and they’re like, ‘Oh, OK!’ It’s creating that web to keep going. I’m also finding young Black kids who play jam band music.”

Decades into the jam band scene, there seems to be a changing tide. Once reluctant to join and wondering where they fit in, Black people are forging their own fandom-within-a-fandom. It’s a trend that longtime fans say they believe will only continue.

“We’re everywhere,” Duncan said. “We make a way everywhere, and we have a good time everywhere we go. It’s beautiful to see.”

CORRECTION (Sept. 12, 2023, 4:08 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated how long Jermain Christmas has been listening to the Dave Matthews Band. It is three years, not 15. And it misstated the racial identity of Chila Ogelsby. She is half white and half Black/Creole, not all white.