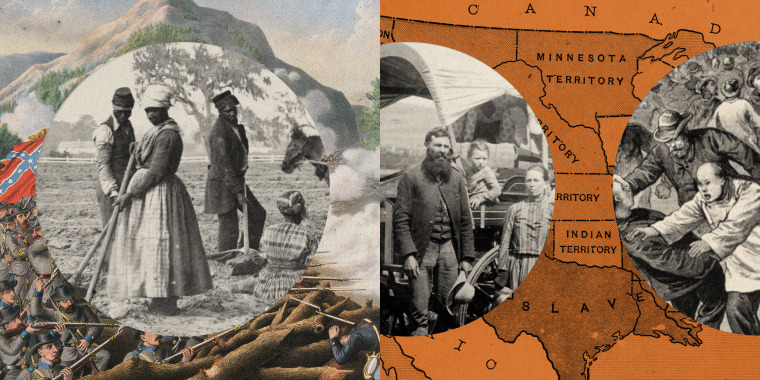

A new study outlines how white people’s migration during and after the Civil War, from the Confederate South to the West, bolstered white supremacy and institutional racism in non-slave states, helping create the vast racial disparities that exist today nationwide.

Five researchers from separate colleges collaborated on the study, called “Confederate Diaspora,” to compile and study census data that tracked the migration to the West of white Americans, including 60,000 former plantation owners. The former Southerners took on local positions of authority, like police officers, clergy and politicians, giving them influence to create a post-Civil War culture that continued to oppress Black people even after slavery had ended.

This results in structural and systemic racism in almost every walk of life today — education, housing, jobs, health care and wealth, among other areas — that continues to hamper progress for Black people, according to a working paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research this month.

The former Confederates “continued to transmit norms to their children and non-Southern neighbors,” the researchers wrote, “shaping racial inequities in labor, housing, and policing.”

Researcher Patrick Testa, an assistant professor of economics at Tulane University in New Orleans, said the impact of the Confederates on other parts of the country was deep and long-lasting.

In the three decades following the Civil War, white Southerners were more likely than other white people to take on work in governance, he said, and former slaveholders were even more likely to assume those positions, he said.

“What we show ultimately is that these migrants,” Testa said, “through these governance channels and channels of public-facing authority, helped lay the groundwork for these types of symbols and racial norms and a broad-base Confederate nostalgia to really take off at a national level by the early 20th century.”

One of those “norms” was the institution of the Ku Klux Klan and the racial terror it inflicted in many parts of the country. In the report, the researchers identify “overrepresentation of first-and second-generation migrants in the KKK,” adding that the second generation of the KKK established in 1915 helped to “rejuvenate and mainstream Confederate culture.”

Those born in the South were 11% more likely to belong to the KKK in the Denver metropolitan area, for example, a major hub of Klan activity in the 1920s beyond the South, the report said.

“The harmful legacies of slavery persist beyond those that experience being slaves, but across generations and across places,” Testa said.

Along with census data, the group of researchers analyzed KKK membership records of second-generation Confederate migrants who were born outside of the South but maintained slavery-era norms. “This suggests,” Testa said, the passing down of racial animus from generation to generation may have been “an important vehicle for sustaining diaspora influence long after the initial Confederate migrants had passed.”

As the California Reparations Task Force is set to hand over its recommendations to the state’s Legislature next week, this new study crystalizes how states that did not legally allow slavery, like California, still contributed mightily to oppressing Black people.

Some detractors of reparations have argued that California was not a slave state and therefore, it should not offer reparations. But in the later part of the 19th century it became the home of numerous former Southerners and it was populated by so many Confederate-aligned citizens that it supported John C. Breckinridge in the 1860 presidential election. Breckinridge advocated for the expansion of slavery and supported the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, which required the return of an enslaved person to a plantation even if he was found in a “free state.”

“It’s important to look beyond the South, even to places like California,” Testa said, “and look for ways such as reparations … to heal these divisions, to heal the socio-economic gaps.”

Because many parts of California favored Breckinridge, it became a popular destination for Southerners at the time. “Outside of the South, California is maybe the most intense in terms of a cultural index that indicates how it accepted racism,” Testa said.

Studying the spread of former Confederates was important, Testa said, because it provides clear data on how the ills of slavery and the Confederate ideology spread across America.

“For the purposes of understanding the multifarious roots of racial division in American society, which continues to be persistent long after, it’s important,” Testa said.