When Victorianne Russell Walton, then 42 in 2007, felt a lump in her breast and saw dimpling around her nipple, she knew immediately what it was.

“I knew it was cancer,” Walton said. “I know my family history.”

Nevertheless, her doctor tested her and said she was cancer free. She insisted he test again. And again. She made a total of four appointments. Each time the doctor told her she did not have cancer.

Walton finally secured an appointment with that doctor’s supervisor. This time Walton got a correct diagnosis: She had breast cancer.

“Had I waited longer, that cancer would have eaten me up,” said Walton, now 56. “It was already in my arm and in my lymph nodes. If I had not fought for myself, I would have died.”

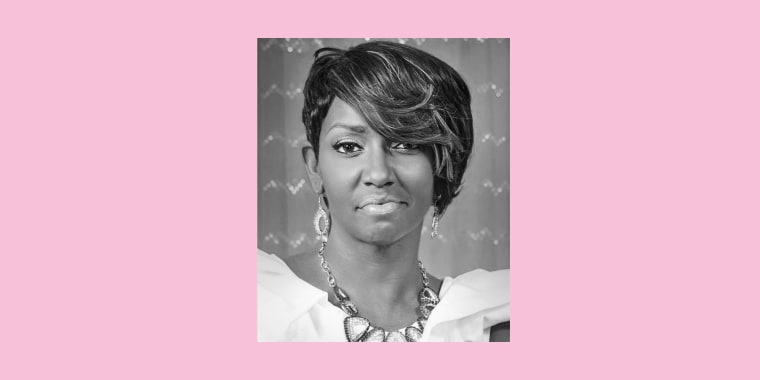

Instead, Walton survived, and now, during Breast Cancer Awareness Month, she said she wants people to stop automatically associating a diagnosis of breast cancer with death. Married and the mother of two sons, Walton is a two-time breast cancer survivor and founder of It’s in the Genes LLC, a health advocacy organization dedicated to advancing awareness and research of potentially hereditary diseases like breast cancer.

Because of her advocacy work, Walton, of Waldorf, Maryland, is featured in this year’s American College of Surgeons’ Your Breast Cancer Surgery toolkit, which offers videos for breast cancer patients and their caregivers.

“Most people hear a death sentence when they receive a cancer diagnosis,” Walton said. “I know African American women who are fighting and thriving. We just need to share those stories.”

Research is being done to look at how breast cancer may affect Black women differently, but race has also been recognized as a social determinant that can influence outcomes for Black women with breast cancer.

Doctors who hold a racial bias or believe medical myths about Black people effect the care for patients of color, according to a 2015 report published in the American Journal of Public Health. Black communities have also been historically underserved by health facilities. Meanwhile, a lack of trust among Black people toward health care providers may prevent some from seeking or continuing care. For Walton, these problems were immediately present when she began to seek care.

“Race was a huge, major factor in my case,” Walton said. “I read a note in my chart that said, ‘Clean, African American woman, spoke intelligently.’ I thought, What does that have to do with cancer?”

A breast cancer diagnosis can be terrifying. Female breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer, overtaking lung cancer for the first time, according to a 2020 report by the American Cancer Society and the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

To Black women, a breast cancer diagnosis may seem even more frightening because of the data. They have a 31 percent breast cancer mortality rate — the highest of any U.S. racial or ethnic group and 42 percent higher than that of white women, according to the Breast Cancer Prevention Partners (BCPP), a policy and advocacy organization. The incidence of breast cancer among women younger than 45 is also higher among Black women than white women.

Triple negative breast cancer, which Walton was diagnosed with during her second bout with cancer in 2018, is a subtype that is both more aggressive and associated with a higher mortality. In the U.S., it is diagnosed more often in women of African descent than in those of European descent, according to BCPP.

Exactly why Black women are diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer more often than other women is one of the many issues being studied by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (BCRF). Dr. Dorraya El-Ashry, chief scientific officer at the foundation, also stressed the importance of knowing one’s personal medical history.

“Knowing your family history, both your mother and father’s side, is very important,” El-Ashry said. “Then a person can say to the doctor, ‘This is my family history. Do I need to get genetic testing?”

Walton was surprised to learn more about her family’s medical history when she talked about her own cancer journey.

“My mother’s grandmother died of cancer, and they had kept it a secret,” she said. “She had both breasts cut off and died. She woke up covered in blood. My Uncle Rufus carried his mother’s body to the end of the road because the ambulance would not come down the dirt road after a rain.”

The stories she heard helped her understand the reasons some relatives did not trust doctors and viewed cancer as a “family curse.” This relationship between the Black community and the medical profession is a work in progress, the strain between the two most recently highlighted by the pandemic.

“We know that Black women are less likely to be included in research and have less opportunity to participate in clinical trials,” said El-Ashry, who explained that clinical trials are “where we validate that a therapy is truly effective and does what it should do in a safe manner.”

In its efforts to increase Black participation in trials, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation is working with the Translational Breast Cancer Research Consortium, which has clinical trial sites across the nation, to increase representation of racial and ethnic groups.

Foundation research is also looking at the intersection of other diseases and health conditions such as diabetes and obesity, and heart disease and their impact on breast cancer outcomes for Black women.

Closing these gaps of care and reducing the impact of these social determinants “will get us to a place where we can more effectively treat Black women’s breast cancer in a more precise and personalized way,” El-Ashry said.

Walton has had two lumpectomies, chemotherapy, radiation and her double mastectomy. She had to get shots in her belly and at another time took medication, leaving her with the side effect of suicidal ideation. Chemotherapy also left her with Type 2 diabetes.

She was told twice that she had a life expectancy of five years. Her family wrote her love letters of encouragement to get her through. One wrote: “You fight with everyone, anyway; why not fight cancer?”

In 2008, while she was receiving treatment after her first diagnosis, she and her husband started It’s in the Genes. One of the ways the organization provides education is through its P.I.N.K.I.E. (or Purposely Involved and Keeping Individuals Educated) Party, where participants are served lunch, receive gifts, can ask experts questions, and can get a mammogram.

Through her advocacy work Walton met Glenda Cousar, who works at Medstar Washington Hospital Center as a breast cancer oncology nurse navigator. The patient navigation model was founded by Dr. Harold P. Freeman, a Black doctor who created the system to address disparities in access to timely diagnosis and treatment. Cousar acts similar to a case manager, resolving patient issues such as providing assistance with transportation, identifying financial support and filling out a multitude of forms.

“For instance, I had a single woman, 39, who mentioned she didn’t have money for gas to go back and forth for treatment,” Cousar said. “People often can’t work 40 hours during treatment because of side effects like fatigue and so they suffer a drop in income. Life does not stop — and copayments are real.”

This is what Walton wants Black women to know, that there are many new resources to aid in their treatment.

“But we have to get the information out there — and share our stories. Superman ain’t coming,” Walton said. “We have to save one another.”