TOMS RIVER, N.J. – Thousands of homeowners in New York and New Jersey impacted by Hurricane Sandy are facing a tough choice that may thwart their efforts to rebuild: Comply with costly new federal construction guidelines or prepare to pay annual flood insurance rates that could top $20,000.

New federal flood maps released in June showed a total of 68,000 structures in New York City and thousands more in New Jersey were in flood zones. Now, affected homeowners are being forced to make drastic changes to their residences, such as elevating them on pilings, or incur punishing new insurance premiums that will take effect by mid-2015. Given the new rules, many Sandy survivors are grappling with whether they should alter their properties – or leave.

“We are faced with something that we can’t overcome,” said police officer Kevin Faller, 52, a Toms River resident who has decided to give up his home rather than comply with the new requirements. Having already lost hundreds of thousands of dollars in home equity post-Sandy, Faller said he and his wife could not afford “this tsunami of expenses coming toward us.”

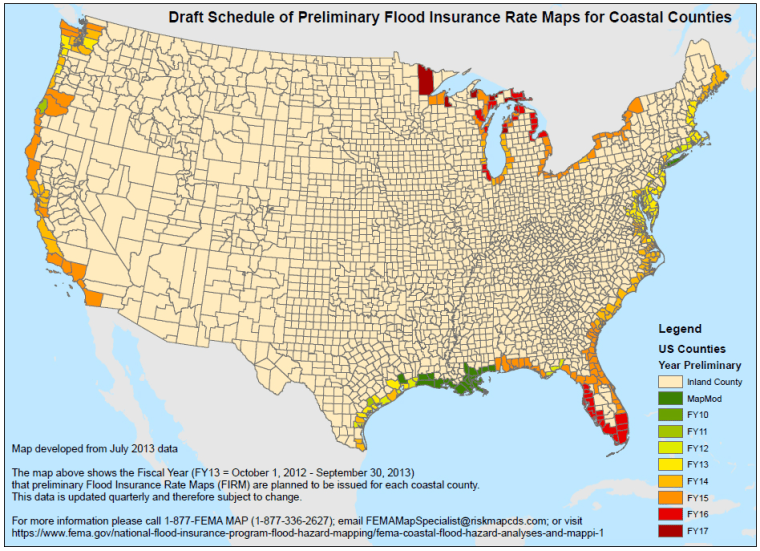

The Federal Emergency Management Agency began updating coastal flood maps across the country in 2009, a process it expects to complete by 2017. In New York City and New Jersey, the work began a few years before Hurricane Sandy struck on Oct. 29, 2012, damaging or destroying 365,000 homes in New Jersey and another 20,000 in New York City. After a public comment period, the region’s maps are expected to become final by mid-2015, putting into effect new insurance premiums.

The agency, which has released estimates showing that rates could range from a few hundred dollars for the most compliant residences to $1,800, $10,700 and more than $20,000, says individual premiums will vary and homeowners must consult an insurance agent to determine what they will pay.

Making matters worse for coastal homeowners, federally subsidized flood insurance for primary residences will start to phase out by late next year, eventually forcing about 1.1 million property owners to pay the substantially higher full-market rates. A law passed by Congress last summer eliminated subsidies for the National Flood Insurance Program, which is $24 billion in debt in the wake of massive storms such as Hurricane Katrina.

“Unfortunately, [Sandy survivors] are suffering through this catastrophic event and they are looking at increased insurance premiums,” said Bill McDonnell, FEMA’s mitigation branch director for New Jersey and an agency specialist for New York. “What we are hoping, though, is that [Sandy] has raised the awareness of the probability of this occurring again” and that homeowners “mitigate their properties to become more resilient.”

“They may be putting out more money now,” he said. “But in the end they are going to suffer less damage to their property and the potential loss of life as well.”

With that in mind, some families are moving ahead to comply with the new requirements despite the cost. Based on an early map released by FEMA in mid-December, Marlo Lutz, 44, and her husband, Darrin, 47, decided to elevate their two-floor Toms River home to 13 feet on pillars and piers, a $65,000 investment that required cashing in a college fund and raiding savings.

“I’ll never have to worry again when there’s a storm,” Marlo said. “Everything about it is just going to be better for us.”

In Breezy Point, N.Y., a coastal enclave hard-hit by Sandy, homeowner Jim Kelly has made a similar calculation. So far, Kelly has spent $104,000 to raise his home to 8.5 feet, with more work to go. He and his wife have used savings and dipped into their 401(k) plans to help cover construction costs, which are expected to reach $220,000.

For Kelly, raising his property has been expensive, time-consuming and stressful, but he said he is just anxious to move his wife Samantha and their 5-year-old son Aiden back home, hopefully by Thanksgiving. “It’s definitely been rough, to say the least,” he said.

Some Sandy survivors are finding the hassle and cost of complying with the new guidelines to be insurmountable.

When FEMA released the early version of the flood maps, John “Jack” Thompson, a 70-year-old mechanical engineer, discovered that his small ranch home in Toms River would have to be raised from six to 14 feet and placed on pilings. If he didn’t comply, he learned, his future annual flood insurance could skyrocket to about $31,000. (FEMA has adjusted that estimate to more than $20,000.)

Though FEMA eased the rebuilding requirements for his neighborhood in June, the value of Thompson’s home has plummeted from around $400,000 to $10,000, according to a county tax assessment. He is contemplating using his flood insurance payments to pay off his mortgage, tear his home down and leave. The storm’s aftermath, Thompson said, has left him financially “dead” and his dreams of retirement postponed.

Meanwhile, half of the homes around him are empty, about ten have been demolished and many are for sale. “It’s depressing. I really hate to think about it,” he said of the changes in his once lively neighborhood situated on tiny lagoons.

Some government aid is available to homeowners trying to meet the new guidelines. New Jersey will provide grants of up to $150,000, a FEMA-funded grant will offer $30,000, and those insured by the NFIP can receive up to another $30,000. New York City said it would also give money to homeowners to elevate their properties through U.S. Department of Housing (HUD) funds.

But according to Marc Roy, chief of staff for FEMA’s Louisiana operations in 2006-07, such grant programs don't always work. He criticized “The Road Home,” a HUD program administered in Louisiana after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita as having had “limited success.”

“That program was marked by all kinds of cost overruns and mismanagement and pretty much has faded from view,” said Roy, an adjunct professor at Tulane University’s Disaster Resilience Leadership Academy. (According to HUD, nearly 130,000 residents – or 99 percent of eligible applicants – had received more than $8.9 billion from the program).

When homeowners struggle to pay for repairs to their storm-damaged properties, some foreclose and leave, devastating the local housing market, said Roy, whose New Orleans neighborhood experienced about ten foreclosures post-Katrina. “Responsible people are having their whole lives ruined … as a result of both the natural catastrophe and the man-made part of the catastrophe, which is poor assistance being available to those who have really worked for it,” he said.

Faller and his wife Karen Spanover, 46, aren't waiting for government aid. In January, the couple decided to give up their home in Toms River, believing that investing at least tens of thousands of dollars to comply with FEMA’s new rules would not be worth it in their struggling neighborhood. They’ve asked their bank to accept a deed in lieu of foreclosure, in which they would hand their home back to the lender.

Faller said he tried to see the tough choice as a business decision, while Spanover said it was ultimately one of “survival.”

“We’ve been fighting for so long,” Spanover said. “Every time we see light at the end of the tunnel it kind of closes. We’re definitely still hoping for the best.”

Are you facing new FEMA requirements for your area? Contact the reporter with your story at miranda.leitsinger@nbcuni.com

Related: