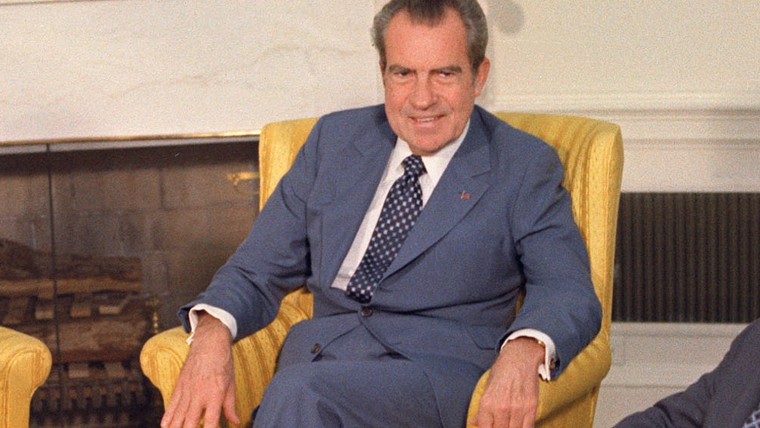

Newly released recordings from 1973 provide ample evidence that President Richard Nixon and his national security aide Henry Kissinger were still running a bold and sophisticated foreign policy in the summer of 1973 even as they fought to keep Senate Watergate investigators at bay.

Nixon was not so consumed by the Watergate scandal that he’d curled himself up in a ball, unable to function as his closest aides resigned in disgrace and his presidency faced ruin. On some days, at least, Nixon was able to seal off the challenges of being investigated by a Democratic-controlled Congress and by a special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, who’d served in President John F. Kennedy’s administration. The tapes show Nixon and Kissinger eagerly pursuing their strategy of playing the Chinese against the Soviet Union as they attempt to conclude a nuclear arms control treaty with the Soviets, preserve the balance of power in the Mideast, and save the regime in South Vietnam from being conquered by North Vietnam.

In a June 4, 1973 phone call with Kissinger, whom he would appoint to be secretary of state later that year, Nixon ponders a new message they’d just received from Chinese leader Mao Zedong, with whom Nixon had met during his historic trip to China in 1972.

“I think that’s quite significant, don’t you think?” Nixon asks Kissinger.

“Oh, I think it’s of enormous significance Mr. President… because it means they think they’re going to deal with you for the foreseeable future,” Kissinger replies.

They then discuss how they can persuade Chinese Premier Chou Enlai to travel to New York to address the United Nations and then stop in Washington for a conference with Nixon.

“It’s going to look rather strange if I go running to China” for a follow-up visit to his 1972 trip “and if he (Chou) doesn’t come here,” Nixon tells Kissinger.

“What he should do is to come to the U.N. and then drop down here (to Washington). And we’ll give him a nice dinner, you know, without the head of state thing,” Nixon tells Kissinger. At that point the United States had not yet formally recognized the Beijing regime as the government of China.

Kissinger also tells Nixon that the Beijing leadership had sent him “a rather good message on Cambodia” – where the United States had been bombing to try to stop supplies and soldiers from North Vietnam going into South Vietnam.

Although the United States and North Vietnam had signed a cease-fire accord in January 1973 to end the U.S. military role, Nixon still was trying to keep the regime in South Vietnam from being defeated. It was not until August of 1973 that Congress cut off funding for bombing Cambodia.

“But we mustn’t refer to that (Chinese message on Cambodia) in any sense,” Kissinger warns Nixon in their June 4 phone call. “And also we must be very careful what we say to the bipartisan (congressional) leaders” on China and Cambodia, he adds.

“I’ll be very careful. Give me some talking points and I’ll futz that, believe me,” Nixon assures Kissinger.

As the call ends, Kissinger takes on the role of morale booster for Nixon. “I think actually the mood is turning,” he tells Nixon, referring to the Watergate scandal’s effect on views of Nixon not only in the United States but abroad. ”Mr. President, the Chinese didn’t have to come back to you in three days,” he says, referring to how promptly Beijing had responded to a Nixon message.

In a June 11 phone call, Nixon and Kissinger are heard making final plans for Soviet Leader Leonid Brezhnev’s ten-day visit to the United States, which would take place the following week. Nixon is eager to persuade the Soviet leader and his retinue to come to his home in San Clemente, Calif.

“It’s a totally controlled situation, we fly to a base, then go in, he’ll enjoy it tremendously, there’s no problem, uh (with) demonstrations, even better than the White House,” Nixon says.

Fresh from a conversation with Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, Kissinger tells Nixon the Russians are still skittish about security at San Clemente. “They’ve also have brought me information of some plots that they have information of which I’m going to ---“ at that point the recording cuts off for 12 seconds, apparently material deleted for national security reasons.

On the June 11 call Nixon and Kissinger discuss Kissinger’s trip that night to Paris to negotiate with North Vietnamese envoy Le Duc Tho. The North Vietnamese were violating the cease-fire accord and Kissinger seems to be worried that the Saigon regime will take some embarrassing step as he tries to bargain with Le Duc Tho. He tells Nixon – who laughs nervously – that he hopes Saigon regime won’t leave them “with egg on our face.”

But alluding to the pivotal role of the Chinese, Kissinger tells Nixon “I don’t know whether I’ve had a chance to tell you actually that the Chinese seemed to come through for us when the North Vietnamese were in Peking because there was a big difference on the speeches which the two sides gave. The Chinese…constantly kept saying, ‘the war in Vietnam is over,’ while the North Vietnamese kept saying ‘the struggle continues.’ And they (the Chinese) put military aid last in the order of priorities of what they were going to do for North Vietnam.”

But as Kissinger noted in his memoirs, when he got to Paris, Le Duc Tho taunted him with reminders that Congress was moving to cut off all funding for bombing in Indochina.

Kissinger said in his memoirs that in the summer of 1973 as Watergate revelations rocked Washington, “We had no choice except to pretend that our authority was unimpaired. For that, we had to do business as usual; we could afford no appearance of hesitation; we needed to project self-confidence no matter what we felt.”

He added that if Nixon had conceded that “his ability to govern had been impaired” it would only “accelerate the assault on his presidency. He could not bring himself to admit the growing disintegration of what he had striven all his life to achieve.”