A growing number of police departments and sheriff's offices in Minnesota won’t enter into contracts to have their officers work in schools in response to a new law that they say restricts how officers can restrain students.

Some police chiefs and sheriffs have said the law — part of a sweeping education bill signed in May by Gov. Tim Walz — does not give officers the right to intervene in dangerous situations and opens them up to criminal charges or lawsuits. The Anoka, Clay and Hennepin sheriff's departments, as well as the Anoka, Blaine, Champlin and Coon Rapids police departments have all suspended the school resource officer program.

“I discussed this with several attorneys who are familiar with this area of the law and they were unanimous: The law is unclear and it could result in litigation that threatens the livelihood of our school resource officers,” Hennepin County Sheriff Dawanna Witt said. “It could even subject them to criminal prosecution for trying to de-escalate a situation by restraining an out-of-control student.”

But Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, who issued a clarification on the matter at the request of the state's Department of Education Commissioner Willie Jett, said the law does not limit the types of reasonable force that may be used by school employees and agents to prevent bodily harm or death. He said in a statement that the law retains the instruction that force must be “reasonable” in those situations.

The law states that an “employee or agent of a district, including a school resource officer, security personnel, or police officer contracted with a district, shall not use prone restraint.” It defines a prone restraint as placing a child in a facedown position. It also states that an employee of a district “shall not inflict any form of physical holding that restricts or impairs a pupil’s ability to breathe,” among other provisions. However, an officer can “restrain a student to prevent imminent bodily harm or death to the student or to another.”

Walz, whose office did not respond to multiple phone and email requests for comment, was asked about the matter at a news conference Tuesday outside of Oak Grove Elementary School in Bloomington, the fourth largest city in the state. A spokesperson for Bloomington Public Schools said it will continue to staff school liaison officers in each of its high schools and will assign one officer to cover its three middle schools.

Walz appeared to reverse course on his earlier position that a special legislative session was not needed to address the matter.

“I think what we’re trying to figure out is, is there a solution that works best to make sure that we have those trusted adults in the buildings, where the districts want them to be, and that it satisfies everyone’s need?” Walz said. “I think at this point in time, we don’t know exactly what that’s going to look like, I’m certainly open to anything that provides a solution to that. And if that means the Legislature working it out to make sure we have it.”

Walz said the value of having these officers in schools is that they are able to build relationships long before anything happens.

“All of those things get averted when we have those relationships,” he said Tuesday. “So I think districts like Bloomington, who have them in, they understand the value of that.”

“The spirit of this thing is, all of us want our buildings safe, and all of us want to make sure that excessive force is not used on our students,” the governor added. “And I think finding that middle ground shouldn’t be all that difficult.”

Jeff Potts, executive director of the Minnesota Police Chiefs Association, estimated that 40% of schools in Minnesota are without a school resource officer. Potts, who was the police chief in Bloomington for 12 years, said he was unaware of any incidents in schools that were the impetus for the legislation.

“Police were blindsided by this law," Potts said. "The law enforcement community learned about it in August.”

Some school districts, including the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Hopkins districts, haven’t had resource officers since 2020, after George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis police custody.

“I would say, three years ago, there was a push to remove SROs and this was in the wake of the murder of George Floyd,” Potts said. “More recently, there’s been a push to keep or add them. There’s been a trend in Minnesota to have them return.”

A spokesperson for Anoka-Hennepin schools said the school district is “currently meeting individually with the five law enforcement agencies that have suspended the SRO program to ensure the best possible plan is in place for school safety as the school year continues” and that its superintendent is involved in these meetings along with police chiefs to determine a plan of action.

Champlin Police Chief Glen Schneider said the state attorney general’s interpretation of the law conflicts with that of city and county officials, from whom many law enforcement agencies sought guidance before deciding not to enter into contracts with school districts.

“The concern for me and possibly others is that there is a limitation where any force can be used when it’s a crime that’s not death or bodily harm,” Schneider said.

Witt, the Hennepin County sheriff, and Schneider, said their decisions will impact one officer from their respective departments.

Witt said there have been no instances of a student being restrained at Rockford High School, where an officer from her department had previously been assigned.

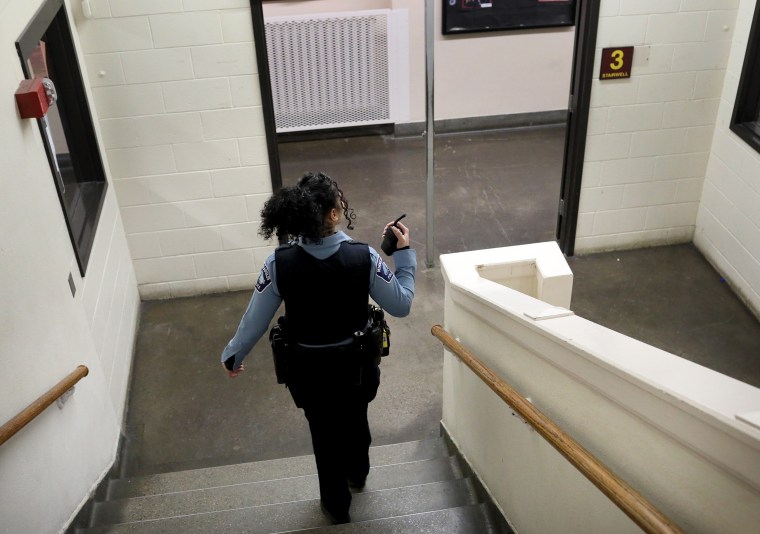

“SRO’s are trained to utilize many types of de-escalation and interpersonal communication skills to navigate incidents at the school,” she said. “Their consistent presence also allows them to build rapport and connection to students.”

Potts said there is already a statute that defines authorized use of force, and that those in law enforcement believe that it should trump the new law.

“The remedy we’re seeking right now is, we offered a proposed change that would basically clarify that a school officer’s use of force is defined by statute 609.06; it can be done very quickly,” he said. “The governor just has to get the House and Senate to come back for a special session. It can happen in two hours.”