Bryan Patrick Miller was sentenced to death this year for a pair of horrific murders that shook Phoenix in the early 1990s.

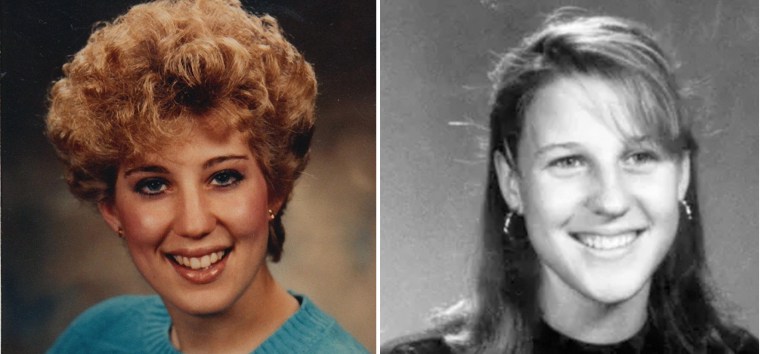

But prosecutors in Maricopa County declined to charge him in a third case from before the killings — the disappearance of 13-year-old Brandy Myers in 1992 — even though retired detectives in the cold case unit that solved the murders of Angela Brosso, 21, and Melanie Bernas, 17, believe he may be responsible for Brandy’s death.

Miller, a steampunk enthusiast known for his elaborate “zombie hunter” costume, is also linked to three nonfatal stabbings that span more than a decade. In one of the cases, Miller was 15 when he was arrested. He pleaded guilty to a charge of second-degree attempted murder in the stabbing.

Although Brandy’s body has never been found and no physical evidence links Miller, now 51, to her disappearance, authorities point, in part, to an apparent confession revealed eight years ago as evidence of his possible guilt. In an interview with an FBI agent and a Phoenix police detective, Miller’s ex-wife told authorities that he admitted to killing a teen who matches Brandy’s description.

“He was our guy,” the former head of the Phoenix Police Department’s cold case unit, Troy Hillman, told NBC’s “Dateline.” “There are many secrets to Bryan Miller that we still don’t know about. We can’t prove it, but we all strongly believe that Bryan Patrick Miller killed Brandy Myers.”

Stuart Somershoe, a retired Phoenix missing persons detective who investigated Brandy’s case, told NBC News, “He will never harm another woman or child, and that’s an important thing.” But, he said, Brandy was nearly forgotten in the drama and the intense media coverage surrounding Miller’s trial.

“That frustrates me greatly, because again, she’s a true victim,” he said. “She did nothing wrong and didn’t deserve the fate that befell her.”

More 'Dateline' cases

- His wife was killed the day before their eviction. A decade later, he faced another foreclosure — and a murder charge.

- After a woman was found dead in the woods, Ohio relied on a well-known forensics expert in the murder case. Was it the right call?

- Couple who bought house from Utah mom charged with killing husband feel like 'bystanders in her path of destruction'

- Days before her death, a Wisconsin woman sent an ominous letter: ‘He would be my first suspect’

Miller, who can send and receive messages from the Arizona prison where he is incarcerated, didn’t respond to requests for comment on Brandy’s disappearance or the other stabbings he has been linked to.

In a message to “Dateline,” he denied being involved in the killings of Brosso and Bernas and said he didn’t agree with the defense presented during his trial. His lawyers had argued he wasn’t guilty by reason of insanity.

Knife attacks in Arizona and Washington

In fall 1989, Miller pleaded guilty to attempted murder after a woman walking through the parking lot of a Phoenix mall said he plunged a knife into her back and fled.

A doctor later said that had Miller angled the blade a little differently, he could have severed her spine or punctured a vital organ, a court filing from the case obtained by “Dateline” shows. The woman, who had been walking to her department store job that May when she was attacked, was “lucky to be alive,” according to the doctor cited in the filing.

Miller was arrested shortly after the stabbing and ordered to remain in juvenile detention until he turned 18. In an email, his lawyer in the recent trial said he was released in summer 1990.

In 2002, after Miller had gotten married, had a daughter and moved to Everett, Washington, he was charged with assault when a woman accused him of stabbing her in an unprovoked attack, according to a probable cause affidavit obtained by “Dateline.” The woman said Miller offered her a ride — and a phone to make a call on — before he approached her with what she described to authorities as a 12-inch knife.

He stabbed her in the back multiple times, causing injuries that required 30 stitches, according to the affidavit.

Miller denied the allegations, and in a legal brief obtained by “Dateline,” his lawyer wrote that the woman had tried to rob him at knifepoint. Her injuries were the result of a struggle that followed, according to the document. Miller took the case to trial and was acquitted.

In 2015, after Miller was charged in the killings of Brosso and Bernas, another Washington state woman saw his face in news accounts and told authorities that he had stabbed her while she was walking on an Everett trail on Oct. 9, 2000, said Somershoe, whose unit investigated the assault.

“She was lucky to survive,” he said. “It was an extremely violent, savage attack” that was “very similar to all these other victims and stabbings from behind.”

The woman was 14 when she was stabbed, and authorities had focused on transients as possible assailants, Somershoe said. Miller — who lived less than a half-mile from the site of the attack — was never interviewed or suspected, he said. By the time the woman contacted authorities after Miller’s arrest, the statute of limitations on possible criminal charges had passed, Somershoe said.

Miller was convicted of fatally stabbing Brosso and Bernas in 1992 and 1993 while they were on bike rides along the Arizona Canal in Phoenix, Hillman said. Brosso was decapitated, and it appeared that Miller had tried to cut her in half, Hillman said.

Ten months later, Bernas’ body was found floating in the canal. Both women had been sexually assaulted, and authorities found letters carved into Bernas’ body, Hillman said.

“It was another horrific scene,” he said.

A stench so bad the neighbors complained

More than two decades later, after a combination of genetic genealogy, DNA and other evidence allowed authorities to identify Miller as a suspect in the killings, a cold case detective and an FBI agent interviewed the woman who, by then, was his ex-wife. They had married in 1997 and were separated by 2005, according to a transcript of the interview obtained by “Dateline.”

She told the investigators that Miller had told her about the fatal stabbing of a person he identified as an intellectually challenged Girl Scout who appeared to be in her mid-teens, according to the transcript.

The killing Miller allegedly described occurred after he was released from juvenile detention on the attempted murder charge, his ex-wife told investigators, while he was living in an apartment operated by a Mennonite outreach program north of central Phoenix.

When the girl knocked on Miller’s door, his ex-wife recalled him saying, he grabbed her, pulled her into the apartment and cut her throat. He allegedly put the body in the bathtub, where he intended to preserve it with cold water, she recalled Miller saying. He mistakenly ran hot water, instead, she said, and allegedly dismembered her body and placed her remains in a trash can.

He “just left the trash can sitting in his house ’til trash day,” she recalled her ex-husband saying, according to the transcript. “When the neighbors complained of the smell, he just told them that some meat in the kitchen had gone bad.”

Miller didn’t identify Brandy by name, according to the transcript. But parts of the account were corroborated, Somershoe said.

Brandy wasn’t a Girl Scout, Somershoe said, but she had been knocking on doors for a book drive when she vanished May 26, 1992.

She was developmentally delayed: Although she was 13, Somershoe said, mentally and emotionally she was closer to 9 or 10. And the date of her disappearance lined up with the ex-wife’s account. It was roughly two years after Miller’s release from juvenile detention.

Brandy was last seen less than 70 feet from Miller’s apartment, Somershoe said.

Mennonites who knew Miller and later talked to Somershoe recalled the terrible odor coming from his home, smells that they described as worse than rotting food, Somershoe said. It was so bad they eventually did an “intervention,” Somershoe said, and cleaned the home while Miller was gone.

That was in fall 1992, several months after Brandy disappeared, and no remains were found, Somershoe said. He added that the people who cleaned Miller’s apartment didn’t examine the trash they threw in a dumpster and that it wasn’t clear what had caused the stench.

Case goes cold

Miller wasn’t suspected in her disappearance at the time, Somershoe said, and the case went cold after an initially promising lead. A man who was later convicted of three killings in the Phoenix area said he would admit to having murdered Brandy in exchange for leniency from prosecutors, Somershoe said. Authorities came to doubt the confession, and no deal was offered to that man, Somershoe said.

Other factors stymied Somershoe and other investigators looking into Brandy’s disappearance. There was no security camera video showing her approaching Miller’s apartment, for instance, or cellphone data pinpointing Miller’s or Brandy’s locations at the time of her disappearance.

A forensic search of the apartment in 2015 yielded little. In the bathroom, investigators found blood, Somershoe said, but it didn’t match that of Miller or anyone else connected to the killings or the disappearance.

An interview investigators conducted with Miller also produced little, Somershoe said. He recalled the case but denied knowing Brandy or having had anything to do with her disappearance or death, he said.

When Somershoe confronted Miller with the alleged confession, he didn’t say who’d disclosed the account.

“He said, ‘Whoever told you that, they’re lying,’” Somershoe recalled.

There was no response to a message left at a phone number listed as Miller’s ex-wife’s. During the trial, she testified about another incident that she said Miller disclosed to her — the stabbing of the 14-year-old on the trail — but she wasn’t asked about Brandy.

In a 2015 interview with The Arizona Republic of Phoenix, the ex-wife recounted the same confession from Miller. She told the newspaper that she wasn’t sure whether he was telling the truth and that she believed the disclosures were an intimidation tactic.

Enough to go to trial?

Even though Brandy’s body had never been found — and even though there was no physical or other direct evidence tying him to Brandy’s disappearance — Somershoe submitted the case investigators had built to the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office for possible criminal charges in late 2015, he said.

"The county attorney basically turned it down, saying ‘no reasonable likelihood of conviction,’” he said. “They’re saying, ‘We don’t feel we have enough to take this to trial and get a conviction.’”

In an interview with “Dateline,” one of the deputy county attorneys who prosecuted Miller in the recent trial said the alleged confession and other circumstantial evidence weren’t enough to definitively link him to Brandy.

“He didn’t give a name,” Vince Imbordino said, so it wasn’t clear “if the description he gave his ex-wife was Brandy Myers or a fantasy.”

“There simply at this point is not enough evidence to be certain that he’s responsible,” he said.

For Somershoe, who retired from the Phoenix Police Department in 2020, that response leaves the case “solved but not resolved.”

“Maybe another set of eyes on this case will lead to some kind of new angle that I didn’t perceive,” he said. “Or maybe Bryan will finally want to unburden his soul and do the right thing and get some answers to his family and to other victims’ families.”

Asked how detectives are now approaching the investigation, a Phoenix police spokesman said Brandy's missing person case remains open and Miller is still considered a suspect.

The department would again submit the case to prosecutors if new evidence is gathered, the spokesman said, "but at this point we have to be open to other suspects."