LAHAINA, Hawaii — Aina Kohler woke before dawn on Aug. 8 and thought she saw a flying saucer hovering outside her window.

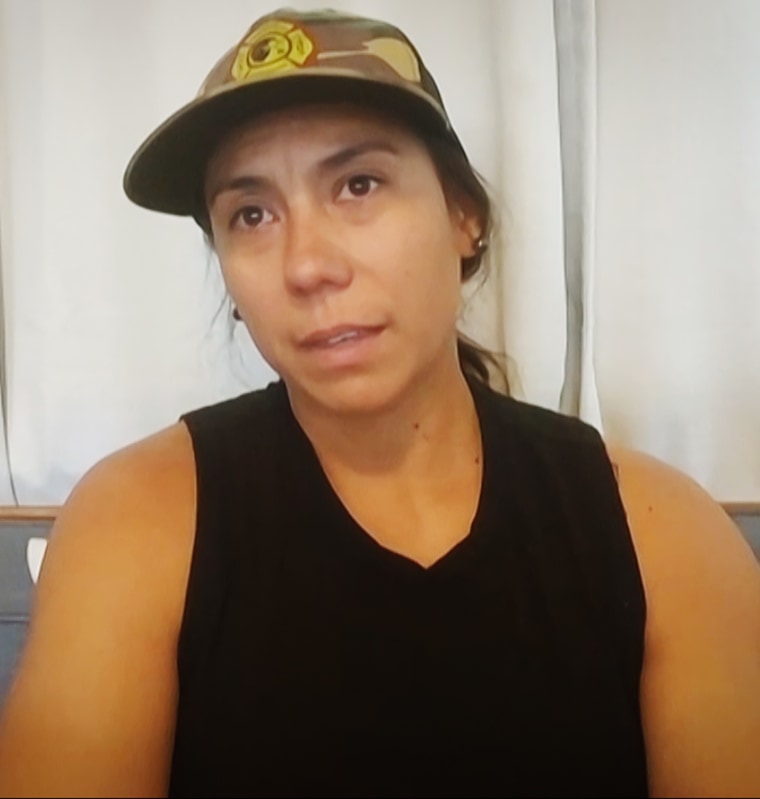

Wind was shrieking past her home in Lahaina, a beach town on the west coast of Maui. Kohler, a firefighter for 13 years who was born and raised here, was due to go into work. It was hot and dry and winds powered by Hurricane Dora had prompted warnings of a high risk of wildfires.

Then Kohler realized what she was looking at. The gales had lifted a neighbor’s kiddie pool into the air over their street. She had never seen wind like that.

She got to the fire station a few minutes before her crew’s 24-hour shift began at 7:30 a.m. The engine, ladder truck and tanker were gone; the overnight crew had been called out to a 3-acre brush fire near a subdivision across town, apparently ignited by fallen power lines.

Kohler and her crewmates put on their wildfire gear — fire-resistant pants and jackets — and drove in a pickup to the scene.

“When we got there we were on edge; the winds were so gnarly,” Kohler, 42, said. “‘What’s next?’ is what we were feeling. We were thinking about where the next fire is going to be.”

The brush fire was in a sloping field along Lahainaluna Road. She saw that the prior crew had gotten most of it out, leaving some spots of smoldering grass and smoke. The incoming firefighters picked up where the others left off, dousing the field with water and turning over dirt.

The gusts remained fierce, surging over the fields and through neighborhoods. Power lines were toppling, trees were falling, homes were getting wrecked. Another truck out of the Lahaina station was responding to some of the calls, as was a crew from a nearby station, Kohler said. A larger brush fire was raging on the opposite side of the island, tying up crews from other stations an hour’s drive away.

“I was watching houses, roofs, just getting torn apart, piece after piece after piece, just flying through the air and kind of just in awe,” Kohler recalled. Her handheld wind meter read 60 mph. “I was hearing that it’s only supposed to get stronger, and I’m like, how much stronger is it going to get?”

And yet they subdued the brush fire. Just before 9 a.m. Maui County declared that it was 100% contained, meaning crews had it fully surrounded but it was not necessarily out. The fire chief and the head of the firefighters union later said that the fire was extinguished. Firefighters had poured about 23,000 gallons of water on the field, a county lawyer said. Kohler and others remained there for several hours, watching for flare-ups and for utility crews to fix downed power lines, she said.

“We walked the perimeter. We walked the inside, and everything looked completely contained and cool,” Kohler said.

More than six hours into their shift, with reports flooding in of destructive winds, the commanders decided it was time to return to the station to regroup, eat and prepare for other calls, according to Kohler; John Fiske, a lawyer representing Maui County; and Bobby Lee, president of the Maui firefighters union.

The firefighters left the scene at 2:18 p.m., Fiske said. According to Kohler, they were back at the station for about 20 minutes. Then, just before 3 p.m., they got a report of a brush fire — in the area they had just left.

There is no official account of how firefighters handled the Aug. 8 wildfires that left at least 97 people dead, destroyed much of Lahaina and wrecked more than 2,000 homes and buildings. NBC News spoke with seven Maui firefighters who helped reconstruct the harrowing race to hold back the inferno and save residents’ lives, their near-death escapes and the snap decisions on where to fight and when to retreat, even while their own homes burned. The firefighters said they wanted the public to understand the unprecedented conditions they faced: catastrophic winds, drought-baked brush, blinding smoke, choked roads, car-melting heat, hydrants that ran dry.

But Kohler could not have imagined any of that when the firefighters got the call to return to the field on Lahainaluna Road. She was just surprised.

“To hear that we were going back there, I was like, you’ve got to be joking,” Kohler said. “How could it possibly be that we’re going back there?”

That fire would go on to incinerate Lahaina.

A crew out of the Napili station, less than 10 miles north of Lahaina, drove by the morning fire scene on the way to and from another call shortly after Kohler’s crew had returned to its station, looking for flames or smoke. Both times, the firefighters didn’t see anything, recalled Capt. Ikaika Blackburn, who led the four-person crew.

About 15 minutes after the crew’s second pass, tones sounded on its radio with the same alarm Kohler had just heard: flames and smoke reported near Lahainaluna Road and Kuialua Street. The crew turned back toward the site and this time the firefighters saw “big smoke,” Blackburn said.

They found a brush fire covering an area of about 20 feet by 100 feet and spreading quickly, Blackburn said.

It was 3 p.m. Forty-two minutes had passed since the morning crew left, Fiske said.

Other crews — including Kohler’s — arrived soon after.

Firefighters positioned themselves to the west of the fire — downhill and closer to the ocean — and sprayed the flaming grass, Blackburn said. For a moment, it seemed like they’d cut the fire off. But the wind gusts, which Blackburn estimated to be about 80 mph, lifted glowing embers and carried them up and over the firefighters’ heads, sparking new fires near Lahaina Bypass, a highway that runs across the mountainside above downtown Lahaina, the former capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom and an economic and cultural hub.

Some embers dropped a quarter mile away or more downwind, Blackburn said.

“It spotted behind us and started to run west toward the bypass. It then jumped the bypass into a little ravine. From that ravine it jumped again,” Blackburn, 40, said. While spotting is common in brush fires, Blackburn said, “this fire is unlike any other fire because it is being fueled by 80 mph winds.”

The small brush fire quickly grew more dangerous.

Around 4 p.m. three crews from other parts of the island responded to a burning neighborhood off Lahainaluna Road. Turning onto Pauoa Street, the firefighters soon recognized that the heat and smoke were too intense, said Capt. Jay Fujita, who led one of the crews. They were about three-quarters of a mile downhill from where Blackburn’s crew first responded.

They decided to retreat, but the street was jammed with people in cars trying to flee. “We were blocked in and we were trying to get residents to move out of the way to safety, but it was gridlock,” Fujita, 52, recalled. “There was no way to move their vehicles and no way to move our engine.”

By then the smoke was so thick that it looked like night, Fujita said. The firefighters tried spraying nearby flames, but their hoses burned apart. They put on their masks and oxygen tanks and got into their rigs, trying to stay calm and conserve air. Fujita said he got on the radio to call for help but got no response; he assumed the heat had damaged the equipment. He tapped out a text message to his wife, telling that her he was stuck and might not make it out, and that he loved her. The message didn’t go through.

After about 15 minutes, it got so hot in Fujita’s truck that the windshield began to bubble. His crew got out of the cab and took shelter behind the truck. He believes it was highly unlikely that motorists near them, without firefighters’ survival equipment, were still alive.

At some point, Fujita said, one of the crews made it out by driving over downed utility poles through a fence and into a park. The crew tried to radio the remaining two crews to describe what they’d done, but the message never reached them, Fujita said.

Another 15 or so minutes went by. A captain on one of the two remaining crews passed out, severely burning his legs on the pavement. Then a police SUV pulled up, Fujita said. A firefighter had dashed from the scene and drove back in the car.

The firefighters carried the unconscious captain and piled into the car with him.

“We just needed to get clear of the smoke and fire as quickly as we could to get medical attention for the captain,” Fujita said.

They drove over what looked like concrete barriers, got onto Lahainaluna Road and made it a mile south out of the fire zone, calling for help, Fujita said. The captain had no pulse. Near the Lahaina Aquatic Center, they performed CPR on him until medics arrived and took him to the hospital, Fujita said. Lee, the union leader, said the captain, the only firefighter injured, eventually recovered after multiple surgeries.

Fujita and the six remaining firefighters returned to battling the blaze.

“We tried our best,” Fujita said. “We tried to do whatever we could and we got to the point where we almost lost our lives.”

Blackburn’s crew, meanwhile, was chasing new fires that had popped up downhill from Lahaina Bypass.

Smoke was blowing horizontally, an effect of the winds that made it difficult to see and breathe. They found a new place to make a stand, only to have to move again. And again. And again.

“The fire was moving through the houses the same way it would move through grass in a regular brush fire,” Blackburn said.

The flames were rolling downhill toward the sea, igniting small fires near downtown Lahaina. They and other crews were ordered to reposition to set up an attack there.

Tasha Pagdilao, a firefighter in the Napili station, was off duty that afternoon. After hearing reports of how bad the fire was getting, she and another off-duty colleague drove into Lahaina to help. On their way in, the smoke thickened. Pagdilao, who was born and raised in Lahaina and whose parents and other relatives still lived there, saw flames lapping at buildings.

At about 4:45 p.m., they reached the Lahaina Cannery Mall, on the north end of town, where a crew was filling an engine with water.

“We have some really tough guys and women in our department that don’t blink, they don’t flinch, they don’t anything. But when I saw them, and I could see tears just coming down, and their uniform and everything was just black,” Pagdilao, 34, recalled. “They came up right away, and they gave me a big hug. And I think that’s when I knew: This is bad.”

The crew was led by Blackburn. Their assignment was to get as close as they could to the heart of historic Lahaina and Front Street, the main commercial thoroughfare. Buildings there were already on fire. They picked a spot near Kenui Street where they thought they could block the fire from advancing north.

They hooked up their hoses and sprayed.

Because they were in their wildland fire gear, which is lighter than the suits, masks and air tanks they wear to fight building fires, the firefighters were more susceptible to the heat, and they could only get so close to the flames before being repelled, Pagdilao said.

As the fire roared into downtown Lahaina, many people were caught by surprise; many later said they did not receive advance warning. The county did not sound an emergency siren system, and many people did not receive emergency text alerts.

By 5:30 p.m., much of Front Street was ablaze. A surge of traffic gridlocked roads out of town. Officials reported people dashing into the ocean. Witnesses heard cars and gas stations explode.

Pagdilao struggled to focus on her job while also watching her hometown burn.

“We thought we’d get a hold of it. And we turn behind, we turn around, and something else is on fire. And it just seemed like we couldn’t win. It was very defeating.”

As the firefighters moved through areas of densely packed houses, some saw their own homes burn but kept working. Downed poles and electric lines made it impossible for firefighters to navigate much of downtown Lahaina.

“You have to triage what is savable and what’s left, try to keep it contained, to not keep doing damage,” Pagdilao said. “That was another of the hardest things.”

At one point, Pagdilao’s crew came across another crew, and she asked if they’d seen what was happening in the Puamana area on the south end of town. That was where her parents lived.

One of them answered: “It’s all on fire.”

By sundown at 7 p.m. the flames had reached Lahaina harbor, where witnesses reported seeing bodies in the water.

The wind shifted and started to blow more to the north than to the west, Blackburn said. The gusts pushed dense, black smoke into the firefighters’ faces. The flames roared toward them.

Blackburn’s crew kept moving from one position to the next. At times the smoke made it impossible to see clearly, forcing them to wait for the wind to lift it away. Sometimes, unwilling to wait, Blackburn barked guidance to his driver while eyeing the road’s white-lined boundaries ahead of them.

“You ever feel helpless, totally helpless? Because this is what we do as firemen, we put out fires, and we’re just helpless in trying to stop this thing because the winds are so strong,” Blackburn said. “We’re throwing everything we have, and it’s continuing to beat us down.”

Through the afternoon and into evening, Kohler and her crewmates chased the fire across the mountainside, in neighborhoods above downtown Lahaina. They hollered at people watering their homes with garden hoses to get out. They picked spots to fight the fire, the streams from their hoses bending sideways with the wind, and taking cover behind their trucks when the toxic plumes swept toward them, only to move again because the heat prevented them from getting close enough to make a difference.

“As we’re going, these people are yelling at us, ‘Our house is on fire, our house is on fire.’ We’re like, ‘We have to go this way. I’m sorry.’ It was just devastating,” Kohler said. “It’s like, how do we make it so that there’s less damage, you know, so all this whole place doesn’t burn?”

They made their way to Komo Mai Street, in the Kahoma subdivision. Setting up with another crew, they connected to a hydrant and began hitting flames. After a while, a captain called out, “We need more pressure.”

Kohler checked the intake line and saw the water pressure had dropped.

It is not clear why some fire hydrants ran dry. Power outages were one factor. Others may include the fire’s destruction of water lines and many crews tapping into the system at the same time.

“You know, sometimes when you’re in a nightmare, you can tell yourself that and then you wake up. And you’re like, yes, we’re in a nightmare,” Kohler said. “And we weren’t in a nightmare. It was very real.”

The crew retreated to an industrial area farther north. They found a hydrant with water and then made a brief stand at a church and a storage facility, Kohler said. They moved to Wahikuli, a northern neighborhood where Kohler lived with her husband and their 12-year-old twins, but the hydrants they tried were dry.

They drove to a brush line above the neighborhood to catch their breath and figure out what to do next. Then they got a call that they were going to be given a break. It was around 8:30 p.m.

“The thought of relief was relieving. And in a sense, the thought of relief was terrifying,” Kohler said. “It’s like, wait, no, we need to stay here and fight this thing till we’re done. Like, we’re not done yet.”

She and her crewmates got into pickup trucks for the drive back to the station. On the way, Kohler saw her home still standing. She was in “mission mode,” she said, and didn’t think of going in.

When Kohler arrived at the station, she found her husband, Jonny Varona, who is also a firefighter, and their children. Without anyone to care for the kids, he’d remained with them through the day.

Varona asked if she wanted him to swap into work for her. “I can’t stop now,” she told him.

She asked him to go to their house, less than a mile away, to get cash and jewelry and other irreplaceable things. But he worried he wouldn’t make it back.

He took the kids to Napili, where many evacuees had sought safety. Kohler went back to work.

She and her colleagues spent the next several hours driving to and from the Lahaina waterfront, past burning buildings, helping to evacuate people who’d been pulled from the ocean.

“We were on robotic mode where we just got to keep doing what we can to help who we can,” she said.

During those runs, Kohler would catch a glimpse of her home. For a while, the house seemed safe. Then she saw that one side of her street was on fire.

Then, around midnight, she saw that her home was on fire.

“I had already accepted it. I think I knew this whole town’s going to burn down, why not my house? Only seems fair, to be honest.”

Around 9 p.m., Blackburn’s crew, including Pagdilao, ended up on the northern stretch of the Lahaina Bypass on a slope that overlooks downtown Lahaina. They and other crews had been assigned to keep the fire from spreading up the mountainside.

Then the fire began spotting north of the bypass, into the Wahikuli neighborhood, Blackburn said. Two crews with them left to try to cut those fires off. That left Blackburn’s crew responsible for protecting the land to the east and stopping the fire from spreading.

Below them, Lahaina glowed red.

“That’s when it really really hit me and that’s when I just broke down,” Pagdilao said. “I’m born and raised in Lahaina. And everyone just started going through my head: my family, my parents, my colleagues, my co-workers who live in Lahaina. My captain, my firefighters, my driver. They all lost their homes and I am just seeing that and just trying to keep it together knowing we still have a job to do. That was a hard reality.”

Blackburn’s crew, with help from private water tankers, spent the night moving up and down the bypass, checking for spot fires and putting them out.

By dawn, the gales had subsided and officials lifted the high wind warning. Blackburn’s crew managed to hold back the fire from moving up the mountainside. Helicopters dropped water on the area.

When the sun rose, shining on Lahaina below, the destruction of the town became palpable.

The crew was relieved at around 12:30 p.m.

They headed back to the Napili station, covered in soot and dirt and smelling like smoke, and showered.

“Then I went home and cried,” Pagdilao said.

Kohler’s shift ended at 7:30 a.m. on Aug. 9. She reunited with her family in Napili. Her children went to stay with a friend. Varona, her husband, went to work on a ladder truck, putting water on hot spots in Wahikuli. At 2 p.m. she finally slept for the first time in 33 hours.

She woke two hours later and thought about the countless decisions that had taken her to one location instead of another. What if she had taken a different course? Would it have changed anything?

Those questions still replay in her head.

“I don’t know that anything could have been done differently,” she said later. “But I sure like to think about it and just beat yourself up over it and think about what you shoulda, coulda, woulda.”

After returning home, Pagdilao began trying to reach her parents.

Cellphone outages made it hard to connect. But she found a spot in Napili with service and got through to her mother and father. They’d fled and survived unhurt, but they did not know the extent of the fire’s destruction. Lahaina was ashes and scorched rubble.

“I had to tell them Lahaina’s gone,” Pagdilao said. “Then I had to tell them their house is gone. And a lot of our family’s houses are gone, and our friends’ houses are gone.”

She later learned that her uncle, a 75-year-old great-grandfather who was partially paralyzed after a stroke, had died while he and his wife of 49 years were trying to flee in a car. Stuck in traffic, he urged his wife to leave and save herself. She survived by running into the ocean.

Pagdilao returned to work at 5 p.m. on Aug. 9, after just a few hours off.

Many firefighters, including those who lost their homes, took few breaks in the days that followed. Some volunteered to work shifts for exhausted colleagues. Others joined search-and-rescue missions. Blackburn helped set up a relief fund for 17 firefighters, four lifeguards and two paramedics whose homes burned to the ground, he said.

“We still have a job to do,” Pagdilao said. “Our fire station doesn’t close. We’re still running calls like medicals or flare-ups, and we’re doing what we would do every day.”

Kohler worked a couple more shifts after Aug. 9, but when she wasn’t on calls she felt overwhelmed with sadness.

She hasn’t been back to work since; she plans to return at some point.

“You have good days and bad days,” Kohler said. “The bad days are very sad, maybe something gets to you, like a video on Instagram, thinking about something you lost, or seeing someone who lost someone. But then you have good days, and you understand that this is going to be a process.”

On the bad days, Kohler said, she has to “fight through the thoughts that want to take you over and take you to a place where you’re useless and where you can’t change anything because it’s already happened.”

It could take years to develop a full picture of how the fires started, how the government responded and whether anyone is to blame.

The cause of the fire, including whether the afternoon brush fire was connected to the morning brush fire in the same location, has not been determined; it is the subject of a joint investigation by Maui County and the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. The state Department of the Attorney General has hired an independent research firm to review the government’s response.

Some residents of the Lahainaluna Road neighborhood have questioned the firefighters’ decision to leave the scene of the morning fire. Firefighting experts told NBC News it wasn’t unreasonable to leave a 3-acre fire zone after a brush fire had been contained for five hours.

More than two-dozen lawsuits have been filed since the fire, most of them blaming Hawaiian Electric for failing to take sufficient safety measures. Kohler and Varona — who lost two businesses, a surf shop and a cafe, along with their home — are among several residents accusing Hawaiian Electric of negligence. Maui County is also suing the utility, and is being accused of negligence itself.

In one lawsuit, Maui residents alleged that the fire department “lacked the resources to stop an all-out firestorm” and that after the morning fire was declared 100% contained, Maui County “apparently ignored the risks that another, perhaps even more dangerous, brush fire could happen.”

Fiske, the Maui County lawyer, said the firefighters' tactics and decisions during the morning and afternoon fires were in line with common practices for handling a wildfire. They left the scene of the morning fire as part of standard protocol that allows firefighters to “rehab” — clean hoses, return equipment and eat, Fiske said.

“When they decided to leave the area, it was in the context of the importance of regrouping because they felt that area was under control and there were other things happening around the county,” he said.

Fiske added: "The firefighters did what they were supposed to do."

Hawaiian Electric declined to comment on any lawsuits.

Firefighters say they have been trying to focus on what they can do now, rather than dwell on what happened.

“What’s next?” Pagdilao said. “Who can we help? Is your family taken care of? Do they need a place to stay? Where are the kids going to school? Just trying to try to move forward.”

Blackburn has leaned on his faith, assuring himself that God always has a plan, even in a disaster. He has encouraged his crew members to talk about what they went through, and to cry over it, to hug their families.

He has also told his colleagues that while they did not defeat the fire, they were not to blame.

“We lost to the beast, and we’re not used to that,” Blackburn said. “That’s not usually what happens. We usually can overcome adversity. But everything was put against us.”