A new ban on “no knock” warrants in Minneapolis, enacted in the wake of Amir Locke’s death, is being called one of the strongest of its kind in the nation.

The policy, which took effect April 8, no longer allows the Minneapolis Police Department to apply for or execute warrants without knocking and making their presence known first. It mandates that officers repeatedly knock, announce themselves and wait at least 20 seconds during the day or 30 seconds at night before entering.

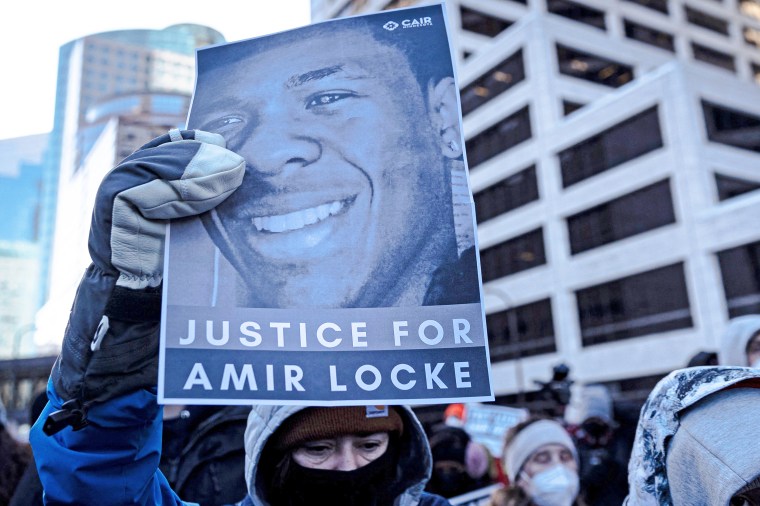

Locke, a 22-year-old Black man who was an aspiring musician, was killed when SWAT officers conducted a “no knock” warrant in the early morning hours of Feb. 2 at a Minneapolis apartment. The officers found him on a couch covered in a blanket with a gun in his hand. An officer shot him three times.

Fury followed when it emerged that Locke was not the subject named in the warrant.

Hennepin County Attorney Michael Freeman and Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison on April 6 announced no charges would be filed in Locke’s death, but admitted Locke might still be alive if it wasn’t for the raid.

“Amir Locke is a victim. This tragedy may not have occurred absent the no-knock warrant used in this case,” they said in a joint statement.

The rallying cry at protests — “end 'no knocks' now!” — is now cemented as policy.

However, with the new regulations police can forgo announcing under “exigent circumstances”: to prevent harm, provide emergency aid, prevent destruction of evidence (excluding narcotics) and prevent escape of a suspect. Similar exigent circumstances are standard in other city and state policies.

Accountability is built into the policy, too. It will create an online dashboard to track forced entries by the department, and there will be an independent review of high-risk and nighttime warrants immediately afterward.

Minneapolis is joining 21 cities and 29 states that have legislation or policies restricting “no knocks,” according to Campaign Zero, a police reform group that helped Minneapolis create the new policy.

Five states — Connecticut, Florida, Oregon, Tennessee and Virginia — have banned them altogether.

Katie Ryan, chief of staff for Campaign Zero, called Minneapolis’ move “a huge victory.”

“I think this is one of the most forward-thinking, most restrictive policies for search warrants in the nation,” she said.

If this policy was in place in Locke’s case, he would still be alive, "because they were at his house at night," she added.

"They either would have been there during the day, they would have waited 20 to 30 seconds, they maybe wouldn’t have been there in the first place, because they would have had to make sure that the individual they were seeking was home, and they weren’t,” she said.

Ryan said the policy has a “really tight definition” of exigent circumstances to prevent warrants from escalating without urgent need and includes a more robust warrant application process to determine risk.

DeRay Mckesson, co-founder of Campaign Zero, emphasizes how crucial wait times are in serving warrants, especially as Locke was killed within seconds of the raid.

“Louisville waits 15 seconds, Maine and Maryland 20 seconds, Minneapolis is 20 seconds in the day, 30 seconds at night — there is no other place in the country, city or state that has 30 seconds at all. What they did has literally not been done,” Mckesson said.

He said this policy is crucial because it regulates how all search warrants are performed to prevent knock-and-announce warrants from turning into “quick knocks.”

He pointed to the case of Breonna Taylor, the Black EMT who was killed during a raid in Louisville, Kentucky, in 2020. Police had gotten a “no knock” warrant but claimed they executed it as a knock-and-announce because they knocked and yelled before entering her apartment.

“The reason why the change in Minneapolis is actually so big, the real way to do this anywhere is to actually restrict the execution of all search warrants so that neither can turn into raids,” McKesson said.

But not everyone is on board.

Sgt. Betsy Brantner Smith, the spokesperson for the National Police Association, warned that the ban could restrict law enforcement’s ability to “proactively stop crime and conduct appropriate investigations.”

“Waiting 20 to 30 seconds is a long time for someone to not just run out the back door, but to get a firearm to start shooting through the door,” she said. “Remember, police officer murders are on the rise.”

In 2021, 61 officers died from felonious assaults by firearm, a 36 percent jump from 2020, the National Law Enforcement Memorial and Museum reported.

She explained “no knocks” are “extremely rare” and typically require multiple layers of authorization, including by a judge. However, Minneapolis was using the raids quite frequently. In 2020, Mayor Jacob Frey said the city’s police department executed an average of 139 “no knock” warrants a year.

In the Locke case, Brantner Smith noted the subject of the warrant was Locke's cousin Mekhi Camden Speed, who was 17 at the time and wanted in a homicide investigation in the January murder of Otis Elder. At the time, Speed had been on probation for another shooting, and he had violated his probation terms.

Brantner Smith said a “no knock” was used because “Mr. Speed was a convicted, violent criminal” who “should have been in jail” and the warrant was for the safety of officers.

“The biggest lesson learned in this situation is not ‘let’s not do no-knock warrants,’” she said. “The problem is a lax criminal justice system.”

'No knocks' are deadly on both sides of the door

“No knock” warrants were born under President Richard Nixon in the 1970s as part of the war on drugs, said Rachel Moran, an associate professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law who focuses on police accountability.

“You can think of police bursting into the home of purported drug dealers and snatching up the drugs before the dealer has the time to flush it down the toilet,” she said.

Their use was popularized with the militarization of police, Moran said. However, “no knock” warrants were thrust under a harsh spotlight after Taylor’s death.

“They’ve always been dangerous. 'No knock' warrants are too dangerous to justify their use,” Moran said.

There is a lack of comprehensive data and oversight documenting such warrants and their impacts, but a New York Times study found that from 2010 to 2016, 94 people died during such operations. Eighty-one were civilians and 13 were law enforcement officers.

“No knocks” are also used in a racially disparate manner, Moran said.

Minnesota state officials mandated law enforcement agencies to report how often they use “no knocks” last year. Data from Sept. 1, 2021, to Feb. 2 show that of the 94 warrant subjects whose race were reported, 70 percent were Black, the Minnesota Post reported.

Alternatives to 'no knocks'

Minneapolis is often compared to its twin city, St. Paul, which hasn’t carried out a “no knock” warrant since 2016, St. Paul police spokesperson Steve Linders told NBC News.

“The decision was made in the interest of safety for everyone involved,” Linders said.

“Rather than force the issue, we’ll use time, distance and cover to achieve the desired outcome. For example, our SWAT team will establish a perimeter and call out people inside the home, apartment, building, etc. If we reach a point where it’s necessary to go in to look for a suspect, we’ll send in a robot or canine first, whenever possible,” he said, adding, “So far, it seems to be working well for us.”

In Louisville, Breonna’s Law was passed in June 2020, banning “no knock” warrants and requiring any Louisville Metro Police Department or Metro law enforcement to knock and wait a minimum of 15 seconds for a response. The state restricted their use in April.

In 2020, St. Louis passed an ordinance to ban “no knocks” for drug cases, and San Antonio's police chief said he banned the practice for officers.

In September, the Justice Department placed new limits on "no-knock" warrants to situations where an agent has grounds to believe knocking and announcing would “create an imminent threat of physical violence to the agent and/or another person.”

Still a ways to go

Still, Minneapolis’ policy could go further.

“One way is a longer waiting period and the other, more importantly perhaps, I would have recommended that they ban nighttime entries,” Moran said. “Does this prevent a tragedy like what happened to Amir Locke? It makes it less likely. … I don’t know if that would have saved his life. I hope so, but I’m not sure.”

Johnathon McClellan, president of the Minnesota Justice Coalition, said the new policy is “too little, too late,” especially after Frey had proposed prior policies that claimed to ban “no knocks,” but didn’t.

“We hope that it prevents the next Amir Locke. I think that the community is skeptical,” he said.

He’s pushing for the state Legislature to pass a bill on “no knock” warrants, proposed in February in the wake of Locke’s death that awaits a final vote on the House floor.

“Amir Locke was not the subject of a warrant,” McClellan said. “Amir was a child still trying to figure out his trajectory in life. Amir Locke could have been any one of us.”