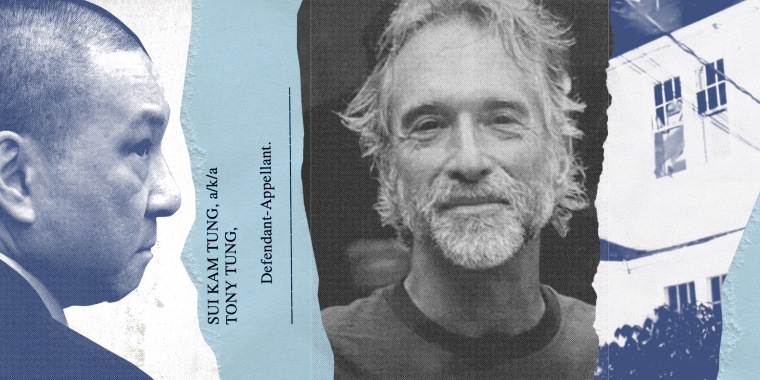

On Dec. 15, 2015, after a two-month trial and four days of deliberation, a New Jersey jury found Sui Kam “Tony” Tung guilty in the brutal murder of his ex-wife’s new partner, Robert Cantor.

Cantor’s sister, Leslie Padron, had been anxious about whether prosecutors could land the conviction: Authorities had no murder weapon, no DNA and no proof that he’d even been in the same town as her brother the night of the killing. It was a relief when the jury returned its guilty verdict, she said.

But last year, after an appeals court overturned Tung’s conviction over improper evidence, the anxiety turned to agony as another round of court proceedings got underway, Padron said.

“We knew he was [going] to put us through this again,” Padron said of Tung. “To draw this all up to the surface, to make it so raw all over again, was just horrible.”

In her first interview about her brother’s murder, Padron spoke to NBC’s “Dateline” about facing the man accused not once but twice of murdering her brother — and about what it was like to observe the prosecution’s efforts to send Tung, 60, to prison for the murder of Cantor on March 6, 2011, at his home in Teaneck, New Jersey, just west of New York City.

Tung was convicted again in July, and he was sentenced to life in prison in November. He has denied killing Cantor, 59. In an interview after his first trial, Tung told “Dateline” he had no clue who was responsible for Cantor’s death.

“How would I know?” he said. “I’m in New York.”

Set off by an affair

Prosecutors argued that the killing was motivated by rage. In early 2010, Tung installed spyware on a computer that belonged to his then-wife, Sophie Meneut, and discovered her affair with Cantor, according to the decision in Tung’s appeal that overturned his conviction.

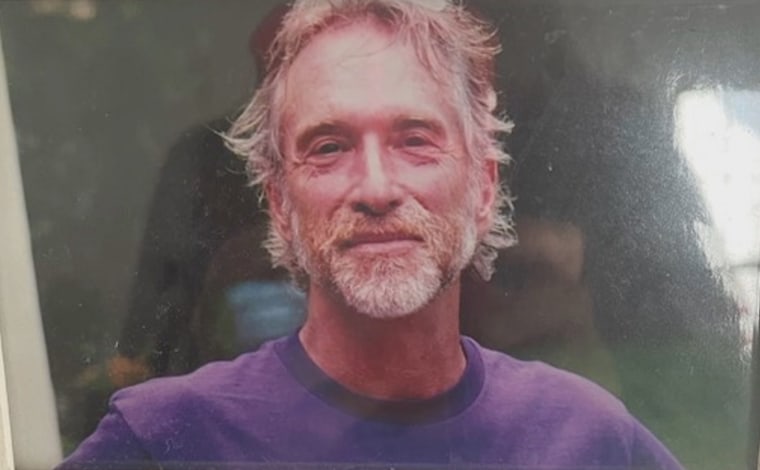

Meneut later told a jury that her marriage was already in trouble when she began seeing Cantor, a computer scientist known for his curiosity and a love of food and running, several months before. After he learned of the relationship, Tung repeatedly went to Cantor’s home, according to the decision. Once he stayed three hours, telling Cantor to stop seeing his wife and asking to see where in the house they’d had sex.

On the night of March 6 — the week Meneut filed for divorce — Cantor’s home burned. Authorities found Cantor’s body in the basement bedroom that he’d shown to Tung. He was lying on the bed and had been shot once in the head with a .380-caliber pistol.

Coincidences or connections?

No physical evidence connected Tung to the crime scene — prosecutors assembled a case built on circumstantial evidence.

Four months before the killing, for instance, Tung emailed a friend in Texas asking for a gun magazine. The friend didn’t send the magazine, which was for the same caliber weapon used to fatally shoot Cantor, according to the decision. (Tung described the request to “Dateline” as a “conversation starter.”)

Hours after Cantor’s body was found, Tung wiped 2 gigabytes of information from his computer — something Tung’s lawyer from the first trial said was a “normal” thing to do at that time of night.

And in an interview with police, Tung said that on March 6, he’d remained at home for much of the night washing dishes and looking at his computer — even though forensic investigators found the device had been in sleep mode that night and a security camera showed Tung leaving his apartment after 10 p.m., according to the decision.

“It’s actually statistically impossible for all of these to be coincidences,” Bergen County assistant prosecutor Joseph Torre told “Dateline.”

Still, the nature of the evidence concerned Cantor’s family: “It was all circumstantial,” Padron said.

More 'Dateline' cases

- An Arizona man was cleared in his stepdaughter’s disappearance. His son is convinced he’s guilty.

- A killer known for his ‘zombie hunter’ costume is on death row, but some suspect he has another victim.

- His wife was killed the day before their eviction. A decade later, he faced another foreclosure — and a murder charge.

- After a woman was found dead in the woods, Ohio relied on a well-known forensics expert in the murder case. Was it the right call?

- Illinois nurse who was terrorized by her ex turned to the court for help. She was dead a year later.

- Days before her death, a Wisconsin woman sent an ominous letter: ‘He would be my first suspect’

An agonizing wait at the courthouse

Padron felt she needed to attend the trial because authorities had revealed little about what happened to her brother, she said. By the time the case went before a jury, it had been more than four years since he was killed.

When the jury’s deliberations stretched to four days, Padron grew nervous. So did Mehrdad Sanai, a close friend of Cantor’s who also attended the trial.

“We thought maybe they [would] call it a mistrial,” he told “Dateline.”

When the jury finally returned a guilty verdict on the fourth day, Padron’s reaction was complicated.

“Guilty is what you want to hear, and you are so happy, and yet then you realize you got justice; you didn’t get happy,” she said. “You feel like you should be celebrating, but you really don’t feel like celebrating.”

Tung was convicted of multiple charges, including first-degree murder, second-degree aggravated arson and second-degree desecration of human remains. He was sentenced to life in prison.

Enough for a new trial

Tung’s lawyers appealed the verdict, arguing the trial judge improperly allowed evidence showing that Tung declined to let authorities search his property without consulting an attorney first. And during the trial, they said, the judge improperly allowed the officer to testify that he knew Tung was lying during the interrogation.

The appeals court agreed with Tung’s lawyers, writing in a 2019 decision that the issues had deprived him of a fair trial. The three-judge panel overturned the conviction.

“That was horrific,” Padron said. “It’s one thing when you’ve been advised that they have new evidence.” But in this case, she said, “it was a few statements. They were nothing drastic, but in the legal system that was cause to give him a second trial. And we knew he knew he was guilty as hell.”

Sanai was also floored by the decision.

“I questioned this crazy justice system,” he said.

“I know a lot of innocent people are sitting, rotting out,” Sanai added. “You find out [Tung] needs a second chance, right, within four, five years. Are you guys kidding me?”

During the first trial, Sanai said, he delivered a victim impact statement recalling his close friend as a “very lovely human being” and pleading with the judge to lock Tung up and throw away the key. But when the second trial got underway last year, he didn’t attend, saying the proceedings made a “mockery” of the justice system.

Padron attended, however, and described having a different experience from the one she had had eight years before. The initial trial was emotionally intense, she said. The second was less so, she said, but her feelings about Tung had only grown more dismal: “He did this to us again,” she said.

Pandemic-related delays made the experience even more awful, Padron said. Still, when the trial began, she wanted to be there to show support for her brother. Her son-in-law, daughter and grandsons also attended.

“We owed this to him,” she said.

Padron said that on July 28, when the jury returned a verdict in less than three hours, her family wasn’t even at the courthouse. They hadn’t been prepared for it to conclude so quickly. But they soon learned he’d been found guilty of eight crimes, including murder.

For Padron, there was a key difference between the two trials.

Now, she said, “we knew this was over.”