As the military wrestles with an alarming number of sexual assaults — an issue former Defense Secretary Leon Panetta called "an affront to the basic American values we defend" — the Department of Defense has adopted a novel technique that fundamentally changes the way investigations are handled.

Hundreds of investigators and prosecutors across all military branches have participated in a special victims unit course at Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri that focuses on a unique forensic interviewing technique designed to elicit detailed descriptions of an attack.

With traditional methods, this “psychophysiological” evidence has previously been difficult to obtain from both the victim and suspect, but can often break open an otherwise difficult case in which there is little or no physical evidence.

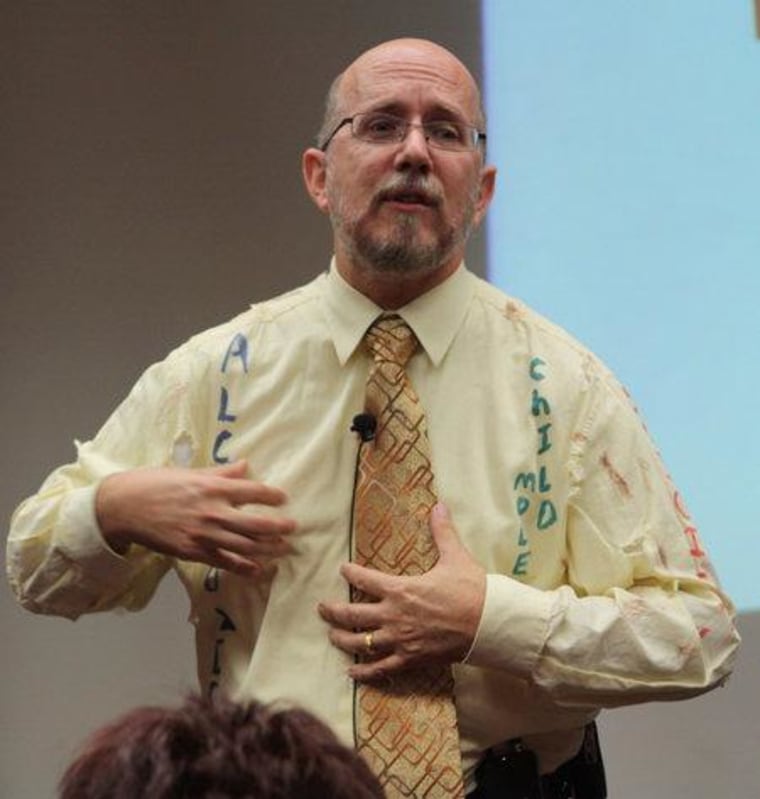

The technique was developed by Russell W. Strand, a former special agent with the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division and current chief in the education and training division at the Army’s Military Police School. Strand began evaluating sexual assault training in 2004 as numerous reports of rape in combat zones and at home became public.

He soon discovered that law enforcement, both military and civilian, expected victims to recount their trauma blow by blow, with precise details that could convince any skeptical jury or judge.

That may seem like conventional wisdom, but Strand frequently found victims rarely had such clarity. He consulted experts, immersed himself in neurobiological research, and found that the expectation doesn’t align with the science of trauma and memory.

In the midst of an assault, the brain does not capture every moment of trauma as if it were recording a film. The pre-frontal cortex can "shut down" or become severely impaired. As a result, many victims can’t provide a contextual or linear account of the event, but fragmentary memories, perhaps the tone of the suspect's voice or, when a sense of defeat has set in, a recollection of the way a lamp looked as she or he was being assaulted. In interviews with investigators, Strand said, the lack of a victim’s ability to recall specifics quickly sowed doubt.

“We started looking at that (research) and started looking at what kind of evidence we gather in a sexual assault,” Strand said. “We weren’t collecting the right data.”

Start with memories, not at the beginning

Strand’s technique, which he has termed the forensic experiential trauma interview (FETI), begins with an investigator expressing empathy toward the victim in order to establish trust. What comes next is not a set of rapid-fire questions about the assault. Strand believes that approach, long used by law enforcement, pressures and confuses the victim. Instead, investigators are trained to simply ask what the victim is able to remember about the experience.

Asking the victim to “start at the beginning” — another hallmark of traditional police work — forces the victim to try to retrieve memories that may not have been encoded in the first place, which can lead to inaccurate or distorted recollections. Some victims may then doubt the memories they do have while investigators wonder if he or she is making up the assault.

What’s more important, according to Strand, is eliciting the victim’s sensory memories, which helps to create a three-dimensional picture of the attack. It also allows the victim to relate the experience in a way that makes sense and yields vital information that can be presented to a jury.

Dr. Jim Hopper, a clinical instructor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, says Strand is teaching good clinical skills for interviewing traumatized people, adapted for an investigative context. Hopper is a guest lecturer for the course, and teaches the effects of sexual assault on the brain.

Lori Jones, a civilian special agent stationed at Fort Leonard Wood, said that once she was trained in the interviewing technique, she was able to collect much better evidence. If a victim describes feeling “frozen” during an attack, for example, Jones is able to understand that as tonic immobility, a physiological response to terror or trauma that often leaves a person numb, starring in a fixed or unfocused manner and unable to move or cry out.

The interview technique can also lead to unwitting admissions of guilt by attackers. When asked to describe a victim's behavior, suspects and victims have recounted the same details, Jones said.

“One of the biggest blessings in FETI has been being able to take forward an investigation with no tangible evidence,” said Jones. “I have the ability to take this to my supervisor and say, ‘This is what the victim is articulating, these were the things she felt her body doing ... and he saw her doing what she was doing.’”

This critical information has helped Jones educate commanders and prosecutors who falsely assume that a victim’s lack of resistance or inability to immediately call the police, for example, is evidence of lying.

Joanne Archambault, a former investigator and executive director of the nonprofit training, education and policy organization End Violence Against Women International (EVAWI), said that evidence gathered by techniques like FETI are essential in conducting a thorough investigation. The interview is a "big piece of the puzzle" that helps an agent corroborate a victim's account.

"Victims are much more likely to talk to us when they’re being given an opportunity to provide a narrative in their own terms," Archambault said. "You can’t get to prosecution and conviction without that."

'Visionary' technique

There are other investigation techniques that attempt to obtain sensory details from victims, but integrating scientific research on how a victim's brain responds to trauma is a unique element that has won Strand accolades. Last year, EVAWI gave Strand its Visionary Award.

Archambault, who investigated or supervised 10,000 sexual assault cases at the San Diego Police Department before retiring in 2002, said that law enforcement often has little or no training in interviewing victims of traumatic crimes. As a result, the experience can feel like an interrogation. She has observed a FETI training class, which Strand also teaches to civilian police departments, and says the focus on about trauma and its effect on memory is novel.

“In a nutshell,” she said, “he’s been dedicated to making improvements in a culture.”

The struggle to understand and address sexual assaults in the military has been very public. Last week, members of the Senate Armed Services Committee excoriated military leaders for permitting an environment that enables sexual assault.

In 2011, 3,192 sexual assault reports were filed, but the Department of Defense says the number is closer to 19,000 based on anonymous surveys of active-duty service members conducted in 2010. Of the 3,192 reports, only cases on 1,518 subjects were brought forward for disciplinary review.

The Army tracks the number of cases brought forward by prosecutors; anecdotally, Jones said it appears FETI has helped increase this number, but the Army's Criminal Investigation Command did not have those statistics readily available. Those familiar with the technique are hopeful that it is changing pervasive attitudes and assumptions about victim behavior.

In a statement to NBC News, Rep. Niki Tsongas, D-Mass., who chairs a caucus on military sexual assault, called FETI a “step toward more successful investigations and prosecutions.”

The Department of Defense has incorporated the course as part of its multi-pronged approach to prevent sexual assault in the military. "When one does occur, effective processes and trained professionals must be in place to support victims and ensure delivery of justice," Cynthia O. Smith, a spokeswoman for the DoD, told NBC News.

Since 2009, 721 special agents and prosecutors from every branch of the military have attended the training. Another 315 are scheduled to complete the course by the end of this September, and DoD has funded more than 400 seats at the course through fiscal year 2017.

Strand says he and his team encountered some early resistance from investigators accustomed to the traditional interviewing technique, but that dissent has since ebbed.

“We’re over the (point) where more people get it than don’t,” he said.

Rebecca Ruiz is a reporter based in the Bay Area.

Related:

- Senate panel members suggest overhaul of military justice system

- Accuser in Air Force sexual assault case 'frustrated' at overturned verdict

- Civil Rights Commission urged to order audit of military sex-assault cases

- Reported sex assaults leap 23 percent at US military academies

- Sex-assault victims in military say brass often ignore pleas for justice