Five Americans imprisoned in Iran have been placed under house arrest in the first step of a planned prisoner exchange between Tehran and Washington that will include the release of roughly $6 billion in Iranian government assets blocked under U.S. sanctions, according to multiple sources with knowledge of the matter.

If the proposed agreement goes through, Iran will be allowed to access the funds only to buy food, medicine or other humanitarian purposes, in accordance with existing U.S. sanctions against the country. Under the agreement, which could take weeks to carry out, Qatar’s central bank will oversee the funds, the sources said.

Republican lawmakers harshly criticized then-President Barack Obama when he made a similar agreement in 2015. The new deal has been under negotiation for months, with Qatar and other governments acting as intermediaries.

Several of the detained Americans were taken on Thursday from their cells in Tehran's notorious Evin prison to a location in the capital where they will remain under house arrest until the prisoner exchange occurs. One of the Americans was apparently already under house arrest before Thursday, a lawyer for one of the detainees and the other sources said. In the past, Americans and other foreign inmates due to be freed have been put under house arrest before their transfers abroad.

The U.S. government has identified three American citizens held in Iran — Siamak Namazi, Emad Shargi and Morad Tahbaz. Two additional Americans are being held in Iran, but their families have chosen not to identify them publicly, the White House National Security Council said.

“We have received confirmation that Iran has released from prison five Americans who were unjustly detained and has placed them on house arrest,” said National Security Council spokesperson Adrienne Watson.

“While this is an encouraging step, these U.S. citizens — Siamak Namazi, Morad Tahbaz, Emad Shargi, and two Americans who at this time wish to remain private — should have never been detained in the first place.”

The U.S. “will not rest until they are all back home in the United States,” she said.

“Until that time, negotiations for their eventual release remain ongoing and are delicate. We will, therefore, have little in the way of details to provide about the state of their house arrest or about our efforts to secure their freedom,” Watson added.

An unknown number of permanent U.S. legal residents, or green card holders, are under detention in Iran, including Shahab Dalili, who has been held since 2016. The prisoner exchange appears to involve only U.S. citizens.

A source familiar with the negotiations told a group of reporters earlier: “It’s the start of a process that eventually will see these Americans leave Iran and come home.”

Jared Genser, pro bono counsel for Namazi, called the move to house arrest “an important development,” adding: “While I hope this will be the first step to their ultimate release, this is at best the beginning of the end and nothing more. But there are simply no guarantees about what happens from here.”

NBC News first reported on the prisoner exchange negotiations in February.

The families of the Americans held in Iran say their loved ones are “hostages” taken captive on false charges and used as bargaining chips by the government. Human rights groups say Iran has been engaged in hostage-taking for decades, wielding foreign prisoners as leverage over other governments. Iran denies the accusation and says the foreign nationals have been treated in accordance with the country’s laws.

Apart from the exchange of prisoners held in both countries, the prisoner swap deal involves the release of roughly $6 billion that has been frozen in South Korean banks by U.S. sanctions.

From 2012 to 2019, Washington allowed South Korea and other countries to buy Iranian oil but blocked Tehran’s access to proceeds from the sales. The funds could only be used by Iran for permitted humanitarian-related purchases. Iran’s government has long demanded access to the money in return for the release of Americans imprisoned in Iran.

The source familiar with the negotiations told reporters that “this was not an account that was ever intended to be frozen for all time for any purpose. It was always meant to be available for non-sanctionable trade.”

President Joe Biden will likely face a torrent of criticism from Republicans if the funds in South Korea are released. Administration officials are expected to argue that the funds can be used only for humanitarian purposes and that it was the only way to secure the freedom of the detained Americans, several of whom have been held for years with no prospect of an early release.

Obama came under fire from Republicans in 2015 when his administration gave Iran access to cash that had been blocked by sanctions, just as Tehran released a group of imprisoned Americans.

The movement of the Americans out of prison is only the first step in a protracted process that could last weeks. The funds to be unfrozen in South Korea will have to be converted into different currencies as requested by Iran, a lengthy process due to the provisions of U.S. sanctions.

As part of the swap, an unknown number of Iranians detained in the U.S. will be transferred from U.S. custody to Iran. The timing of that step remained unclear.

Apart from Qatar, the governments of Oman, the United Arab Emirates and Iraq also played supporting roles as intermediaries in the discussions, the source familiar with the negotiations said. Switzerland, which handles U.S. interests in Iran as Washington has no diplomatic relations with Tehran, will help implement the agreement and the Swiss ambassador is expected to have access to the American detainees during their house arrest.

In addition to the prisoner exchange, the two sides have also discussed a possible informal verbal agreement aimed at averting a crisis over Iran’s nuclear program, NBC News has previously reported.

The proposed arrangement would have Iran possibly freeze its uranium enrichment at current levels of 60 percent purity and fully cooperate with inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency. In return, the U.S. would not impose new sanctions or possibly not strictly enforce some existing sanctions. The precise outlines of the proposed arrangement remain unclear.

U.S. officials have denied there is any interim nuclear agreement but sources with knowledge of the talks say the two sides have been discussing an informal, verbal understanding designed to freeze the status quo and avoid a confrontation. Under U.S. law, any formal agreement would have to be reviewed by Congress.

Iran has steadily expanded its uranium enrichment work and has enough fissile material for more than one nuclear weapon if it chose to enrich the material to 90% purity, experts say. If it takes that step, U.S. officials fear Israel might opt to take military action to prevent Iran from developing a nuclear weapon.

Iran has denied it is planning to develop nuclear weapons and says the program is for purely civilian purposes.

Biden came into office promising to revive the 2015 nuclear deal between Iran and world powers known as the JCPOA that imposed limits on Iran’s nuclear activities in return for lifting U.S. and international sanctions.

Then-President Donald Trump pulled the U.S. out of the agreement in 2018, reimposed sanctions and introduced additional ones. Negotiations on restoring the 2015 nuclear accord collapsed last year.

The three Americans held in Iran that have been publicly identified by the U.S. are Morad Tahbaz, an Iranian American who also holds British citizenship and was arrested in January 2018 and convicted of espionage in 2019. Tahbaz was part of a group of environmental activists carrying out research on Iran’s endangered cheetah population.

Emad Shargi, an Iranian-born businessman who moved to the U.S. as a young man, was arrested in April 2018. He was released on bail and cleared of all charges in December 2019, but Iranian authorities refused to return his passport. Shargi was charged again in 2020 and convicted on espionage charges without a trial.

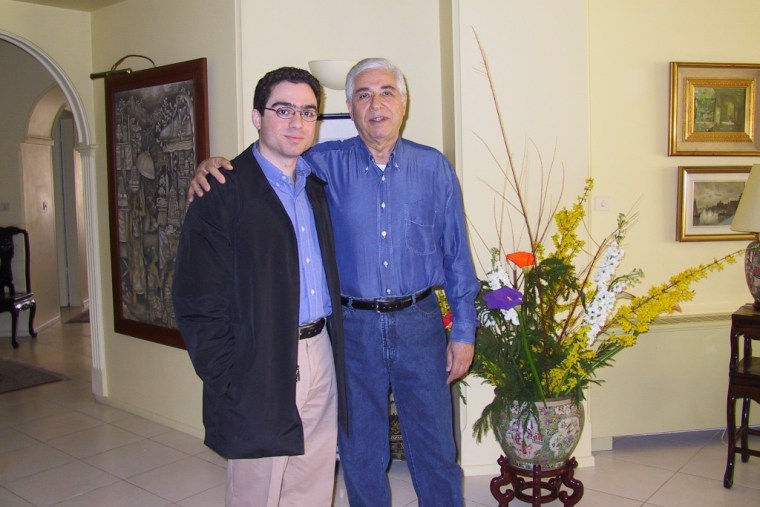

And Siamak Namazi has been held prisoner in Iran for nearly eight years, longer than any of the other current American detainees. A business consultant with degrees from Tufts and Rutgers universities, Namazi was arrested in 2015 and convicted of espionage in a trial that lasted a few hours. His elderly father, Baquer, was arrested in 2016 when he traveled to Iran to visit his son and detained. Baquer Namazi was released in 2022.

Siamak Namazi has criticized the U.S. for not doing more to secure his release and that of other Americans held in Iran and appealed to Biden to meet with the families of those detained. In January, he went on a weeklong hunger strike. Namazi was not included in previous prisoner exchanges with Iran dating to 2016.

The American captive held longest in Iran is believed to have been Robert Levinson, a retired FBI agent who disappeared during a business trip on Iran’s Kish Island in 2007. U.S. officials later admitted that Levinson was there doing contract work for the CIA. In 2011, his family released photos and a video in which Levinson pleaded for help and said he was in poor health. Iranian officials steadfastly denied knowing anything about him.

In 2020, the family announced that they had concluded that Levinson had died in captivity, citing information provided to them by U.S. officials. “Those who are responsible for what happened to Bob Levinson, including those in the US government who for many years repeatedly left him behind, will ultimately receive justice for what they have done,” the family said in a statement.

CORRECTION (August 10, 2023, 3:29 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated who the source was on the outlines of the planned prisoner exchange. It was several people with knowledge of the deal, not a lawyer for one of the detainees.