LONDON — Poop stains are rarely cause for celebration.

But they are the reason Antarctic researchers have been able to identify four new colonies of emperor penguins — a species threatened with extinction by climate change.

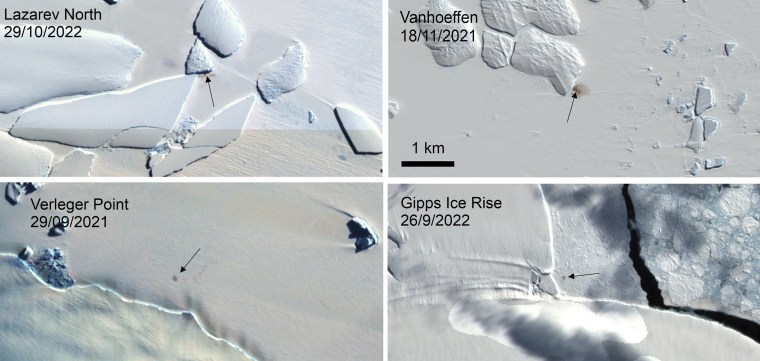

A scientist from the British Antarctic Survey used satellite imagery to spot tell-tale patches of the penguins’ guano (a technical term meaning bird poop), visible from space as a series of brown smudges against the vastness of the White Continent.

The four colonies most likely existed for years but hadn't been spotted until Peter Fretwell, a geographic information officer at the British Antarctic Survey, pored over the images. Some of the colonies appear to be moving as climate change threatens the Antarctic sea ice on which they live and breed.

But while the discovery is invaluable for researchers, they caution it does little to alter the dire long-term prospects for the species, whose sea-ice habitat is being melted by global warming.

“By the end of the century we think that almost all emperor penguin colonies will no longer be viable,” Fretwell, who made the discovery, said in a telephone interview Wednesday. “They’re not going to survive in the long run.”

Emperor penguins are classed as "near threatened," with around 600,000 of them remaining — a 50% drop over the past half-century, according to the World Wildlife Fund.

The four discoveries bring the total of known emperor penguin colonies to 66, Fretwell wrote Saturday in the journal Antarctic Science. The findings “give us an idea of the distribution and where the colonies are, and that’s really, really important if we’re going to monitor how they adapt to climate change,” he said. “But it doesn’t change the big picture that much.”

Emperors are the largest species of penguin, often weighing around 90 pounds. But the giant flightless bird also has one of the most precarious breeding practices on Earth.

To ensure their chicks fledge in the summer, they breed at the coldest time of year, when temperatures near minus 50 Fahrenheit and Antarctic winds howl at 120 mph. Male penguins keep chicks warm by balancing the eggs on their feet, and colonies of up to 5,000 huddle together to keep warm — shuffling around so each one gets a turn on the inside, according to the British Antarctic Survey.

But the animals do all of their breeding on Antarctic sea ice, which last year reached its lowest maximum since scientists began measuring in 1979. Some scientists fear the decline is so extreme that humanity has lost control of what is now an unavoidable snowball effect.

If an ice sheet breaks up before a colony of emperor penguins sees its chicks fledge, the young birds will fall into the water and die, Fretwell said. That’s what happened over the past two years, in particular 2022, when there was a “total breeding failure” in all but one of five known breeding sites, according to another study by Fretwell published last year.

The new colonies Fretwell identified are mostly small. And at least some of the penguins appear to have moved because of unstable sea-ice conditions, he said in the article in Antarctic Science.

"When the colonies fail, they will move to other areas," Fretwell told NBC News.

“We spend all this time monitoring these animals and seeing if they can adapt to climate change, but really, in the end, it's not the penguins that need to adapt, it’s us,” he added. “We need to stop our addiction to fossil fuels — not just for penguins, but for all species, even ourselves.”