Russia’s apparent pursuit of a nuclear space-based weapon has stirred a frenzy in Washington — and raised a flurry of questions among a world of scientists and experts.

With scant details released from the congressional briefings, it’s unclear exactly what sort of weapon the Kremlin may be pursuing, and just how bad it would be for the West if President Vladimir Putin does deploy one.

This could be an alarming escalation of hostilities reminiscent of the tensest days of the Cold War, or a less significant development whose revelation may stem from more mundane domestic concerns than the possibility of nuclear war in space.

“We know very little, and the comments so far have been very, very cryptic,” said Bleddyn Bowen, an associate professor at England’s University of Leicester and author of “Original Sin: Power, Technology and War in Outer Space.”

Three sources familiar with the matter told NBC News that Russia is developing a nuclear space-based weapon designed to target American satellites. This weapon is not yet operational, the sources said, but the intelligence was enough to prompt Rep. Mike Turner, R-Ohio, the chair of the House Intelligence Committee, to ask the White House to declassify information about an unnamed “serious national security threat.”

The main known unknown, publicly at least, is whether this is a space-based nuclear weapon in the most conventional sense of the term — nuclear warheads, atomic reactions, mushroom clouds. Or if, as many experts suspect, this is a nuclear-powered satellite carrying electronic weapons, which could cause havoc on Earth by crippling satellites that drive everything from weather forecasting and phone calls to wars and the global economy.

If it is the former — actual space nukes — that would be a violation of the United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty of 1967. One of its clauses says that countries are not allowed to “place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit, or on celestial bodies, or station them in outer space in any other manner.”

One of the reasons this treaty was signed is the same reason that stationing nuclear weapons in orbit would be so dangerous: a country could loose a nuclear bomb from the heavens with very little warning. The sources said the Russian technology in question is designed to target American satellites, something experts say Russia — and other nuclear-armed powers — is more than capable of doing using intercontinental ballistic missiles, or ICBMs, launched from the ground.

Nevertheless, actually deploying nuclear weapons in orbit “would be a new escalatory step by the Russian Federation, which has already trashed a lot of arms control treaties,” said Mariana Budjeryn, a senior research associate at the Project on Managing the Atom, part of the Harvard Kennedy School. “This would be putting a nuclear weapon in space — where there have been none before.”

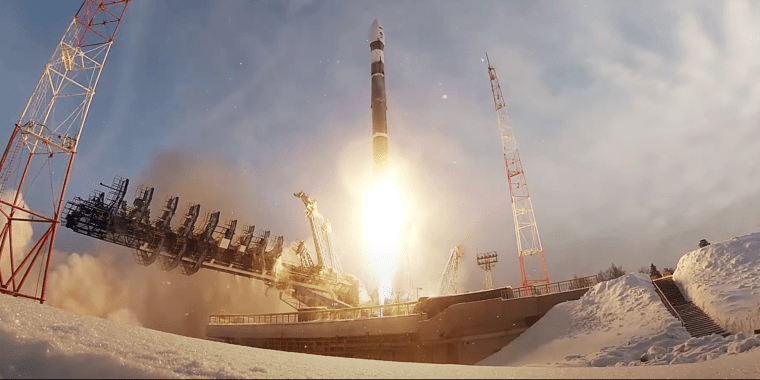

Other experts, reading between the lines of the reports, believe that this weapons system would be nuclear-powered rather than nuclear-armed. There has also been speculation that this is all linked to a classified Russian satellite, named Cosmos 2575, launched last week.

All this said, little if any of these technologies or concepts are new.

Both the U.S. and Soviet Union developed and tested anti-satellite weapons, or ASATs, during the Cold War. And both have regularly used nuclear power in space.

As early as 1959, the U.S. began developing anti-satellite missiles, fearful the Soviets might be about to do the same. This culminated in its 1985 test launch by an F-15 fighter jet, releasing a payload at around 38,000 feet that whooshed into orbit and destroyed a degrading U.S. satellite, according to the U.S. Air Force museum.

Between 1969 and 1975, Washington was able to “cobble together” an anti-satellite system that used existing nuclear missiles in “direct ascent” mode to destroy targets in space, according to a paper published in 2000 by the Air Force’s Air University Press.

In terms of nuclear power rather than nuclear arms, Washington likewise first put a nuclear-powered satellite in orbit in 1961. The Soviets developed and deployed similar technology, which powered many of its satellites during that period.

This is far from without risks, as history has shown.

In 1978, a Soviet nuclear-powered satellite malfunctioned, fell out of the sky, and as it burned up, showered northern Canada with radioactive debris.

What doesn’t appear to have been developed yet, or publicly revealed at least, is something that does all these things at once: a Russian, nuclear-powered satellite carrying a weapon.

If the U.S. has “intelligence that is not about development, but the actual plans to deploy, then, yes, it is a new development,” Budjeryn said.

A nuclear-fueled satellite might be able to carry a high-powered jammer that could block out a wide array of communications and other signals for prolonged periods of time, according to a 2019 technical essay in The Space Review, an online publication widely shared among experts following this week’s news.

Bowen, at the University of Leicester, said such a design would be “really expensive” and “just waiting for a problem to go wrong to then have a nuclear environmental disaster in orbit.”

Ultimately, he and Budjeryn said that none of this technology is new, though its actual implementation would no doubt be viewed as an escalation.

“It’s quite bizarre to me that this is now making such waves,” he said, noting that Russia has been capable of deploying this technology “for a very, very long time.” He added, “You would rather not see more nuclear materials in orbit, but if they do it, on the security front it’s not that big a deal.”

He and others have questioned whether the release of the information may be more about politics than military threat.

“Congresspeople do these things for different reasons,” he said. “Is it about trying to get more information out of the Pentagon, or trying to get Russia in the news? I don’t know.”

That’s certainly the view from Moscow.

“It is obvious that the White House is trying, by hook or by crook, to push Congress to vote on the bill to allocate money,” said Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov, in an apparent reference to the push for new aid for Ukraine, of which Turner is a prominent advocate. “We’ll see what tricks the White House will resort to.”

Others have suggested that this could be a diversion from the other side.

“Russia has tried to develop weapons in space for a long time,” Francesca Giovannini, executive director of the Project on Managing the Atom at the Harvard Kennedy School, said in an email. “We don’t actually know whether this is just a disinformation campaign to force the U.S. to divert precious resources from other capabilities (which are way more important and consequential).”

CORRECTION (Feb. 15, 2024, 11:41 a.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated the height at which an anti-satellite missile was released during a test launch in 1985. It was around 38,000 feet, not at 36,000 feet.