An Arizona county has decided not to hand-count its ballots in next year’s elections, after discovering that it would cost more than a million dollars and leave it with inaccurate results.

The all-Republican Board of Supervisors in Mohave County voted 3-2 against forgoing ballot counting machines in favor of hand-counting in 2024, after months of debate, questions on the legality, and a three-day test run.

“I’m willing to have further conversations about this, but the first thing that we have to do in Mohave County in good conscious is to balance the budget. You can’t talk about any other spending when you have 18 — 20 million dollar deficit,” said Supervisor Travis Lingenfelter, a Republican, before voting against a proposal to hand count all the ballots in 2024. “That’s irresponsible.”

Some conservatives, including allies of former President Donald Trump, have pushed hand-counting ballots as a way to ensure the accuracy of election results. But Mohave County's experience punctures that talking point, showing that hand-counting is typically expensive, inaccurate and impractical.

In short, hand-counting ballots isn’t as easy as it sounds.

Mohave County, home to an estimated 220,000 people in the northwestern corner of Arizona, is one of a handful of U.S. counties that has considered hand-counting ballots, thanks in part to election conspiracy theories that have driven distrust in ballot tabulators.

After the 2020 election, the Arizona state Senate authorized a controversial hand-count audit of two races. The audit took months and cost millions, and — by its leadership’s own account in text messages obtained by The Arizona Republic — failed to result in an accurate count.

But that hasn’t quelled interest in Arizona. Earlier this year, the Republican-controlled state legislature passed a measure authorizing hand counts, which was vetoed by Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs.

In June, the Mohave County’s Board of Supervisors asked the county elections office to develop a plan for tabulating 2024 results by hand. Secretary of State Adrian Fontes, a Democrat, warned Mohave’s county supervisors in a June letter that they risked breaking the law if they chose to opt for hand-counting in a future election. A lawyer for the county told supervisors before they voted that the county’s legal team wasn’t sure it was legal, either.

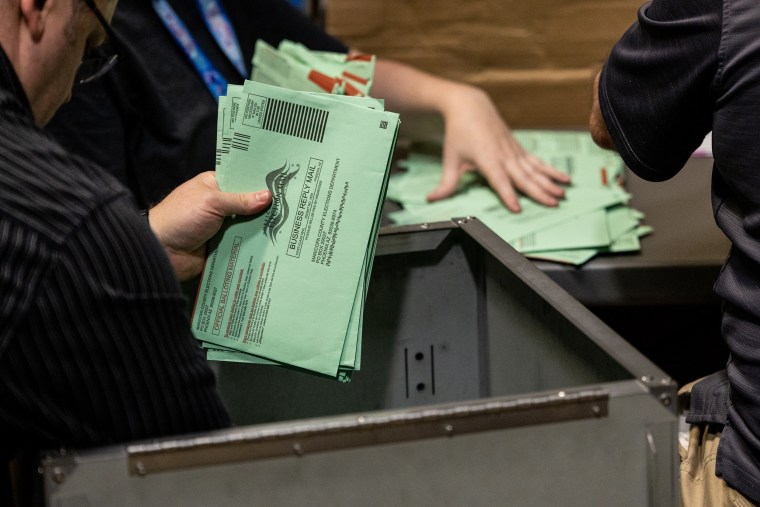

The test run took place in late June, when elections workers spent three days hand-counting a batch of 850 test ballots from the 2022 election, bringing in seven part-time staffers eight-hour days of counting and four full-time staffers who monitored the process.

Elections Director Allen Tempert told the Board of Supervisors at a Tuesday meeting that the group was a “dream team” of experienced staffers, but the feasibility study nonetheless went poorly.

There were counting errors in 46 of 30,600 races on the ballots, as the team tallying the results of the election made mistakes. According to a report prepared for the Board of Supervisors, some of the observed errors included: bored and tired staffers who stopped watching the process, messy handwriting in tallies, fast talkers, or staffers who heard or said the wrong candidate’s name.

Each ballot took three minutes to count, Tempert said. At that pace, it would take a group of seven staffers at least 657 eight-hour days to count 105,000 ballots, the number of ballots cast in 2020. Mohave County would need to hire at least 245 people to tally results and have counting take place seven days a week, including holidays, for nearly three weeks. That estimate doesn’t include the time needed for reconciling mistakes, or counting write-in ballots, Tempert’s report added.

Tempert forcefully recommended waiting until Election Day to conduct the hand-count, because he feared results would leak out otherwise. But doing so would leave the county in a time crunch, too: The county would have just 19 days after the election to tally up the ballots, in accordance with state law on canvassing results.

The total cost for the staffing, renting for a large venue for the counting, security cameras, and other associated costs was staggering: $1,108,486.

“That’s larger than my budget for the whole year, to run the whole election for the whole year!” Tempert said.

Gowri Ramachandran, an elections expert and attorney from the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, said the experiment was notable.

“There actually hasn’t been a lot of experimentation with hands counting full ballots — meaning all the contests on a ballot in a jurisdiction where you have a lot of contests on the ballot,” she said. Ballots had, on average, 36 races each in the test, according to the report.

But Ramachandran said the cost and time it takes to conduct audits and recounts made the results predictable.

“When you put those experiences together," she said, "it’s extremely unsurprising what they found in Mohave County."