WASHINGTON — Cecilia Polanco and Devon Westhill are both members of racial minorities who hold degrees from the University of North Carolina, but they hold starkly different views on their alma mater's consideration of race as part of the admissions process, a policy now under Supreme Court scrutiny.

While Polanco, 29, a Latina social justice activist born to immigrant parents from El Salvador, supports affirmative action policies, Westhill, 36, a Black conservative who served in the administration of former President Donald Trump, is adamantly opposed.

The two alums are on opposite sides of the a decadeslong legal fight now before the Supreme Court in two mammoth cases to be argued Monday. One case involves Harvard University’s admissions policy. The other hits closer to home for Polanco and Westhill: It concerns UNC, an institution in a former slaveholding state that fought against racial integration for decades.

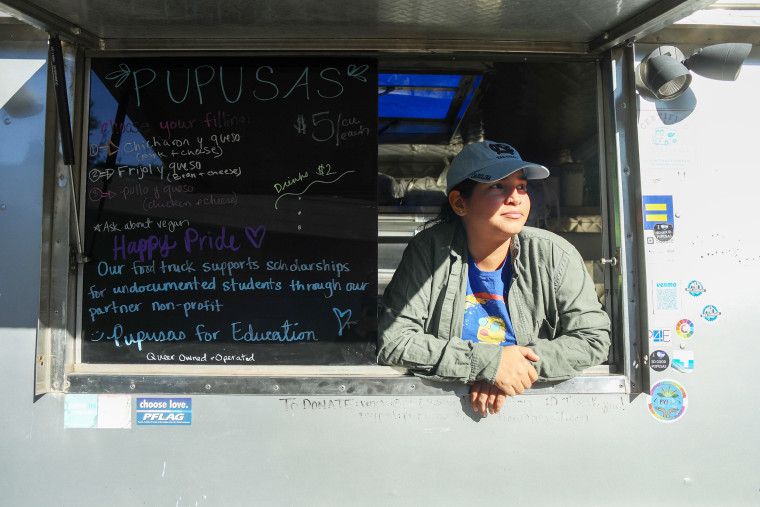

Based in Durham, North Carolina, Polanco’s projects include a food truck selling Salvadoran pupusas that helps fund education grants for undocumented immigrants. She joined other UNC alumni and current students in defending the existing admissions policy in court, saying that her identity as a Latina is an intrinsic part of who she is and was appropriately considered as just one factor during the application process.

“I am a qualified student. That is part of the narrative that irritates me: that affirmative action makes way for less qualified students. That’s not what that means. It means equally qualified. Just as qualified,” Polanco, who graduated in 2016, said in an interview.

Westhill runs a conservative organization in Washington called the Center for Equal Opportunity that advocates against racial preferences. He thinks his UNC degree was tarnished by the university’s admissions policy, because it could create the false impression that he was admitted because of his race. His group has filed a brief backing the challengers at the Supreme Court.

“I have on my resume an asterisk. That’s something that can never be erased. That’s a stigma,” he said. Part of the problem, he added, is that although he feels he deserved to be at UNC, graduating in 2011, there is no way of knowing for sure if his race was the reason he was admitted.

Founded in 1789, UNC’s purpose in educating the white slave-owning elite was “to make young men into masters,” historian David Cecelski wrote in testimony in the North Carolina case backing the use of affirmative action.

When Black students were finally admitted in 1955 to a campus littered with monuments to those who had defended slavery and racial segregation, they were barred from the swimming pool and housed in a separate dormitory, he added.

Polanco and Westhill's contrasting views on the university's efforts to atone for its past practices reflects how affirmative action, introduced to redress historic discrimination, has been a contentious issue for decades, strongly supported by educational institutions and corporate America as vital to fostering diversity and condemned by conservatives as antithetical to the notion that racial equality means that all races are treated the same.

The nine justices on Monday will hear back-to-back oral arguments in the UNC and Harvard cases that are likely to last several hours. Most court observers are expecting that the court’s 6-3 conservative majority will be sympathetic to the arguments against affirmative action being brought by a group called Students for Fair Admissions.

Ed Blum, the anti-affirmative action activist who leads the group, said he hopes the court "will finally end these polarizing and unfair racial preferences in college admissions." None of his group's members who applied to the University of North Carolina and were rejected were willing to talk to the press, he added.

Blum's lawyers have asked the justices to overturn a 2003 ruling on Grutter v. Bollinger, in which the court said race could be considered as a factor in the admissions process because universities had a compelling interest in maintaining a diverse campus. The legal debate on the issue had already raged for decades before that and was left unresolved by a fractured 1978 Supreme Court ruling in which the justices prohibited racial quotas but left the door open to some consideration of race.

The last time the Supreme Court took up a challenge to affirmative action, in another case brought by Blum, the justices in 2016 narrowly upheld the admissions policy at the University of Texas at Austin on a 4-3 vote with conservative Justice Anthony Kennedy, who has since retired, casting the deciding vote.

The court shifted to the right following former President Donald Trump’s appointment of three conservative justices, creating the 6-3 conservative majority. President Joe Biden’s sole appointee, liberal Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, did not change the ideological balance of the bench as she replaced fellow liberal Justice Stephen Breyer. As Jackson previously served on Harvard’s board of overseers, she has stepped aside from that case and will only participate in the North Carolina dispute.

Blum’s group argues that any consideration of race in university admissions is unlawful under both federal law that bars discrimination in education and the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. They argue that the UNC admissions policy discriminates against white and Asian applicants and that the Harvard policy discriminates against Asians. In both cases, lower courts ruled in favor of the universities.

In defending their policies, the universities and their supporters — including the Biden administration, civil rights groups, businesses and former military leaders — argue that excluding someone based on race is completely different to seeking diversity on campus. The universities say race is just one factor that is considered as part of broad individualized analysis of each applicant. Harvard’s lawyers said it was a “false narrative” to suggest that the university was “obsessing over race” when deciding on admissions.

At UNC, about 8% of students identify as Black, 8% as Hispanic and 12% as Asian or Asian American, an expert testified in the case. Data submitted in the Harvard case showed that in each incoming class about 10% of students are Black, 10% Hispanic, and about 20% Asian American.

If affirmative action is ended, those defending the practice say, race-neutral policies aimed at achieving diversity will often fail, leading to a decline in Black and Hispanic enrollment. The challengers point to examples in the nine states that already ban the practice as evidence that consideration of race is not essential.

David Hinojosa, a lawyer representing Polanco and other former and current UNC students who back affirmative action, said the Supreme Court, which has already made major changes to the law this year by ending the right to abortion and expanding gun rights, would have to do something similarly bold in overturning past decisions if it were to rule for the challengers.

“The court would essentially have to rewrite the history, rewrite the facts — and the law — in order to change that precedent,” he added.

CORRECTION (Oct. 28, 2022, 12:05 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated the nature of the Supreme Court decision in the 2016 case concerning affirmative acton. It was a 4-3 decision, not a 5-4 decision