WASHINGTON — President Joe Biden's China policy, still a work in progress, has so far been a tricky balancing act.

He has struck a more measured public tone than his predecessor on some issues but an even sharper one on others, while preserving some of President Donald Trump's confrontational policies — and the Trump administration's overarching view that Beijing is a challenge to be confronted.

Biden described his policy as "extreme competition" with China — an approach that hinges on persuading Congress to pass trillions of dollars in new spending and to unite America's allies in the Asia Pacific region on a strategy despite their often divergent interests.

A senior administration official said that when Biden announces a package of spending proposals Wednesday in a joint address to Congress, he "will talk about the investments necessary for our economy to compete with China," using the same messaging he has in the push for his yet-to-be-passed jobs plan.

While the pairing of China policy and domestic policy isn't new — recent presidents have done the same — Biden has ratcheted up the stakes by arguing in essence that U.S. survival as a democracy depends on how competition with China plays out.

Yet some core planks of Biden's policy, including trade and military strategy, remain undefined. And he has kept in place for now Trump's controversial tariffs on Chinese goods. Several China experts said that overall, much of Biden's policy, while different in tone from the Trump administration's, remains vague.

"There's a lot of lack of clarity, even among people who follow these things really closely," said Susan Thornton, a senior fellow at Yale University's Paul Tsai China Center, though she said the Biden team was viewed as "more unified and definitely more disciplined."

Jude Blanchette, a China expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank, also described Biden's China policy as being in flux while officials "sort through the inheritance of the Trump administration and decide what will be discarded."

"One of the defining hallmarks of the Trump administration was not the policies per se, which of course were aggressive, but the circus and soap opera, Trump zigging and zagging. And you had different elements of the administration openly fighting and feuding," Blanchette said. The Biden administration has been more disciplined, implemented an internal policy process and toned down the rhetoric toward China — even if "we haven't seen Biden's China strategy yet," he said.

The administration is conducting an internal review of U.S. troop deployments around the world. Some military commanders and intelligence officials are pushing to shift more troops and resources to the Pacific to help counter China's massive arms buildup, but it's still unclear how far Biden will be willing to go.

Defense officials expect the Pentagon's China Working Group to wrap up its efforts as early as next month. And a separate internal review of tariffs that Trump adopted on Chinese goods is still underway, senior administration officials said.

Yet administration officials said they don't expect any fundamental shift in Biden's policy as outlined so far, even after the military and trade reviews are completed. More likely, they said, Biden may just make tactical adjustments.

An initiative the administration is actively discussing is a possible alternative to the defunct trade pact between the U.S. and 11 Asia-Pacific countries, excluding China, known as the Trans-Pacific Partnership. A second senior administration official said that a range of options was being considered but that Biden plans to put forward a proposal.

The administration has yet to take what experts see as key steps to counter China's trade practices and forge new trade agreements with other countries. It hasn't, for instance, submitted a nominee for a Commerce Department post that helps decide which technologies are exported to China and which are blocked, nor has it asked Congress to renew the executive branch's Trade Promotion Authority, which allows a president to negotiate a trade deal and submit it to Congress for an up-or-down vote on a scheduled timeline. It expires in July.

Administration officials said the framework for Biden's China agenda is based on three elements: boosting domestic strength by getting the coronavirus pandemic under control and pushing ahead with large spending proposals, coordinating more closely with allies and confronting China on points of disagreement.

Unlike other top foreign policy challenges on his plate, Biden's China strategy has momentum from Congress, where there is bipartisan support for an aggressive approach. Multiple measures backed by Republicans and Democrats are gaining traction, including a bill from Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and Sen. Todd Young, R-Ind., that includes $100 billion to advance technologies in the U.S. to keep pace with China.

The White House has expressed initial support for the bill, and administration officials say such bipartisanship is the type of united message Biden hopes to send to China.

Other bills are a mix of measures to fund projects in the U.S. and blunt what the U.S. views as China's aggressive actions on trade, technology, human rights and military ventures.

Some lawmakers want Biden to be more aggressive.

"So far, President Biden's approach to confronting the Chinese Communist Party has been mixed," Rep. Michael McCaul of Texas, the ranking Republican on the Foreign Affairs Committee, said in an email.

Critics say Biden's moves on China don't set the U.S. on a course to counter a country that the administration has described as the only one in the world that could use its economic, military and technological might to challenge international stability.

"I don't think there's much of a China policy yet," said one of Trump's national security advisers, John Bolton, who has sharply criticized Trump's foreign policy decisions, including those about China.

Biden's emphasis has been on bringing U.S. allies in Europe and the Asia-Pacific region into the fold. One of the first steps was to reach agreements on cost-sharing for basing U.S. troops in Japan and South Korea, which had become a source of friction during the Trump administration. Trump had pushed both countries for large increases in contributions.

Biden also has held a virtual meeting with the leaders of Australia, India and Japan. Yet while courting allies is one of the more notable shifts from the Trump administration, putting forward a united front on China is tricky.

"U.S. allies have generally responded very positively to these efforts," said Patricia Kim, a senior policy analyst with the China Program at the U.S. Institute of Peace. "But having said that, there's also wariness in some capitals on how far they may be asked to go out to call out China on human rights issues or what role they might be expected to play in a potential Taiwan contingency."

The interests of the U.S. and its allies aren't always aligned, given allies' economic and trade interdependency with Beijing.

Among the most concerning issues is China's aggression toward Taiwan. Officials hope to avoid confrontation, although Biden hasn't drawn a clear red line on how the U.S. would react if Beijing made a move — an approach that has drawn mixed reviews.

The administration notably has also not yet publicly labeled China, the suspected culprit, as having been responsible for the hack of Microsoft software. An official said the administration is weighing the process and substantive considerations that go into such a designation but reiterated what the White House has said publicly: that the U.S. ultimately will name the entity behind the hack.

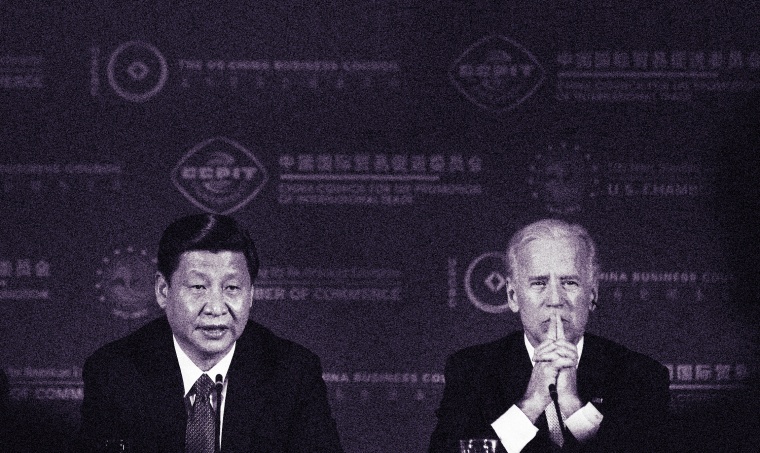

The early sidestepping of confrontation is also apparent in Biden's treatment of China's handling of the coronavirus. Beijing's lack of transparency about the origins and initial spread of the virus hasn't been a top public focus for Biden, who told reporters that he never raised the issue in his roughly two-hour first call with Chinese President Xi Jinping, which administration officials said was intended to set the parameters of the relationship.

The administration has sought to test its self-described strategy of confronting China over differences while trying to work with Beijing when the two countries may have shared interests, such as climate change and a nuclear deal with Iran.

Still, the high-level meeting between the U.S. and Chinese secretaries of state and national security advisers in Alaska laid bare the challenges the administration faces.

Before the meeting, the U.S. adopted sanctions against China for its crackdown on political freedoms in Hong Kong. And Secretary of State Antony Blinken criticized China's use of cyberattacks against the U.S., its treatment of Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang and its overall "economic coercion."

Tensions then spilled into public view when Chinese officials pushed back against criticism with a lecture about the American human rights record, specifically referring to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Administration officials said no more high-level meetings are scheduled — and while they're ready to hear from Beijing about what it sees as the next steps, they're in no rush, they said.