The world's arid areas — deserts filled with scrubby vegetation and sand — are absorbing more of the carbon dioxide that's being emitted into the atmosphere than expected, a new study shows. While these ecosystems will not stop global warming, scientists said the finding provides a better understanding of the carbon cycle, and thus how the global climate will change in the future.

"It is definitely not going to stop it ... just now we are understanding the processes that are going on," lead author Dave Evans, a biologist specializing in ecology and global change at Washington State University, told NBC News. "But we are still seeing huge amounts of carbon accumulating in the atmosphere."

Carbon dioxide is the main greenhouse gas driving global climate change. More of the planet-warming gas is released into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels, and scientists want to know where it all goes. Reconciling this so-called carbon budget has proven one of the trickier areas of climate science, Evans explained.

It's well-known that some of the carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere, and the rest gets stored in the land or oceans in other carbon-containing forms, such as microbes, plants and animals. But the finer details of the process are elusive.

Getting a handle on the budget

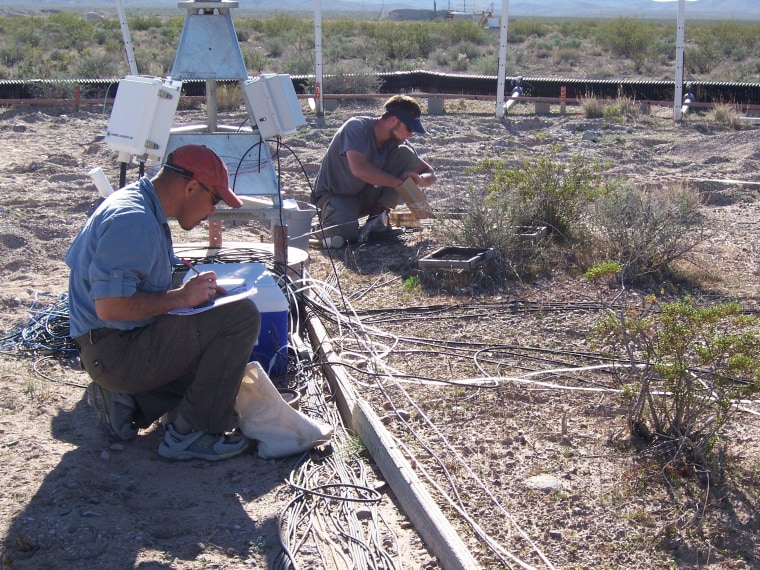

To get a better handle on the carbon budget, several research teams around the world are conducting so-called free air carbon dioxide enrichment experiments, where plots of land are fumigated with the elevated levels of carbon dioxide expected in the future. This extra carbon dioxide has a specific chemical fingerprint that can be detected when the soils and plants are analyzed.

The new findings come from such an experiment, conducted with nine octagonal plots about 75 feet in diameter in the Mojave Desert in southern Nevada. The plots are representative of the arid and semiarid ecosystems that cover nearly half of the Earth's land area.

For 10 years, three of the desert plots received no extra air; three were pumped with air containing carbon dioxide concentrations of 380 parts per million, the current level; and three received concentrations of 550 parts per million, the level expected in 2050.

"After 10 years, the experiment stopped and we dug everything up to ask the question: Is there more carbon under future carbon dioxide conditions than there are under current conditions," Evans said. "And what we found was, there was indeed more carbon. During those 10 years, carbon accumulated at a faster rate under future CO2 conditions."

'Significant' carbon sinks

The findings indicate that these arid ecosystems are "significant, previously unrecognized sinks" for atmospheric carbon dioxide, Evans and colleagues write in a paper published Sunday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Analysis of the data indicates that desert ecosystems may increase their carbon uptake in the future to account for 15 to 28 percent of the carbon currently being absorbed by land surfaces. Overall, according to the paper, rising carbon dioxide levels may increase the uptake by arid land enough to account for 4 to 8 percent of current emissions.

The team found that most of the carbon was being taken up by soil microbes that surround the roots of plants. In contrast, forest ecosystems tend to store carbon in the plants themselves.

Convincing data, unclear interpretation

"The data on carbon storage are convincing," Christopher Field, who directs the department of global ecology at Carnegie Institution for Science at Stanford University, told NBC News in an email. However, he added, "it is not entirely clear" how to interpret the results from a 10-year experiment on a planet where atmospheric carbon dioxide is gradually increasing.

The effect is "unlikely to ever be as large with gradually increasing carbon dioxide," noted Field, who runs a project where similar enrichment experiments are conducted on a grassland ecosystem. Field is also the lead author of a new Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change report warning that the risks of climate change are rapidly accelerating.

"It is worth noting that, although the sink in this experiment is significant, it is … about tenfold less than typical sinks in young forested ecosystems not exposed to elevated carbon dioxide," Field said, adding that "the bottom line is that deserts will not save us from climate change."

Update for 12:00 p.m. ET April 8: Climate scientist Christopher Field initially misstated the carbon-absorbing effect of deserts as opposed to forests in an email. This report has been corrected to reflect his estimate that the effect of forests is 10 times greater.