As climate change diminishes sea ice from coastal communities in the Arctic and the subarctic, researchers expect polar bears to range farther into the towns and camps in that remote part of the world.

Now, researchers in Churchill, Manitoba — sometimes called the polar bear capital of the world — are exploring whether radar technology could provide an early warning of the largest land carnivores’ presence.

They hope the technology, which could cost as little as a few thousand dollars to implement in its smallest form, could become part of a strategy to prevent conflict between polar bears and people from boiling over in a world where fast-rising temperatures are pushing animals out of their usual habitats.

“If we’re asking people to conserve a large predator like a polar bear, we have to make sure people who live and work with them are safe,” said Geoff York, the senior director of conservation and staff scientist at Polar Bears International, which has led testing of several versions of the equipment. The technology could be fully deployed for the first time as soon as next summer.

Churchill, a small village on the western edge of Hudson Bay in northern Manitoba in Canada, offers some of the best access to polar bear viewing in the world. When the sea ice along the bay melts, the bears migrate to make their home on land and wait for the ice to return.

“Churchill is unique in that bears come to shore, depending on the year, from July to August, and they’re on land until this time of year,” York said, adding that as many as 800 bears come ashore near Churchill and nearby Indigenous Cree communities.

Along the Hudson Bay, ice tends to re-form first near Churchill, said Tom Smith, a wildlife biologist at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

“The bears are not feeding. They’re waiting. It provides people an opportunity to see bears in a natural habitat,” he said. “It makes it ideal to test new technologies.”

Although every season is different, climate change is lengthening how long bears are away from sea ice.

“Bears are spending up to 43 more days off the ice,” York said.

Bear encounters are common enough that Churchill has its own bear alert program, which began in 1982. Call a hotline — 675-BEAR — and trained responders will come to haze bears away from town or immobilize them. The program also has a facility to hold problem bears.

For a polar bear hot spot like Churchill, the response program makes sense.

But as climate change limits sea ice habitat, it’s expected to push more hungry bears toward communities that haven’t dealt with these creatures before.

“Places that historically didn’t have polar bears and are going to have more,” said BJ Kirschhoffer, the director of conservation technology for Polar Bears International. “Polar bear alert is a fantastic program, but who is going to have the budget?”

That’s where radar and remote sensing could fill a gap.

Researchers with Polar Bears International have been testing 10 different radar technologies from three different companies to figure out how to best sense polar bears at differing costs and ranges.

The researchers are using machine learning technology developed by the radar companies to better distinguish polar bears from other creatures, snowmobiles or other moving objects.

“We’re really in the testing phase here in regards to this tool and how it interacts with artificial intelligence and things like that,” Kirschhoffer said. “We’re really in its infancy. There are not a lot of people trying to figure this out.”

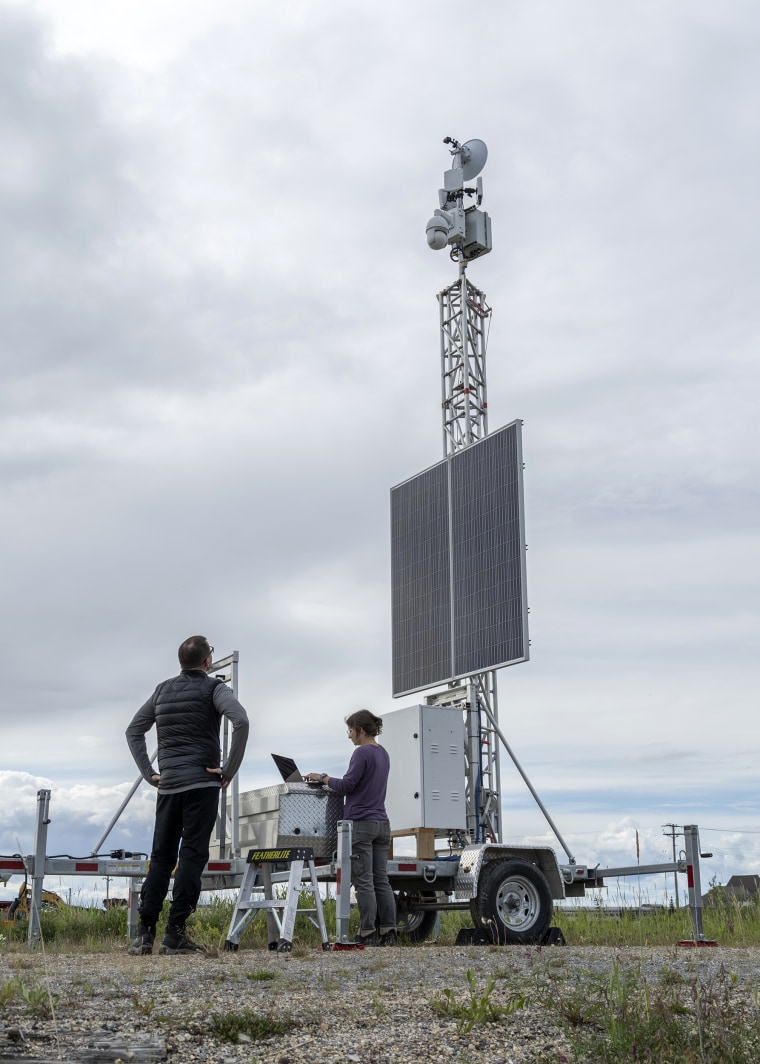

Researchers this year set up one system — from SpotterRF — on a new mobile tower for testing along pathways frequently traveled by polar bears.

The system, which has a range up to about 200 meters (about 656 feet), should be ready for use at a historic fort frequented by visitors to Churchill next summer, York said.

A cheaper short-range system, which was constructed by Brigham Young University students, is slated to begin testing for its second year Monday. The researchers think it could be most useful at identifying bears on a smaller scale — at a cabin or a landfill, for example.

The risk polar bears present to people is often overstated, said the school’s Smith, who is building a database of bear attacks. He said polar bears likely account for about 5% of all bear attacks in North America. Nevertheless, the bears maintain an outsize place in people’s minds.

“I wouldn’t exactly brand them as stalker killers,” he said. “Polar bears represent a small percentage of human bear conflict in North America, but I don’t know, it takes just one polar bear mauling to ruin your whole day.”

A 2017 study documented 73 attacks by wild polar bears from 1870-2014 in Canada, Greenland, Norway, Russia and the United States. These attacks caused 20 human deaths and 63 injuries, according to the paper, published in the Wildlife Society Bulletin.

Attacks are a risk to humans and bears alike. When bears kill, people often carry out retaliatory killings, Smith said, which can further cause stress on a wildlife population dealing with climate change impacts.

Conflict between people and polar bears is expected to escalate. Researchers have documented that polar bears are spending more time on shore as sea ice diminishes. Smith’s research shows that trash dumps are increasingly drawing polar bears toward human populations.

“We showed many villages had many different conflicts and we predict it will only escalate,” he said. “The big problem, of course, is climate change, but it’s one more of a thousand cuts that’s going to cause the demise of this species.”

The researchers hope developing radar technology and bringing it to northern communities could help people adjust to a region being reshaped by climate change.

“If the end goal is to live in harmony with bears, this is definitely going to be another tool in our box to make that happen,” he said.