A shift to plant-based diets is one strategy to help the world meet its food demands by the year 2050, according to a new study that says crop yields are improving too slowly to satisfy meat-eaters' appetites.

"That is a very optimistic part" of the paper, lead author Deepak Ray, with the Institute on the Environment at the University of Minnesota, told NBC News.

He noted that the global middle class was 2 billion out of 6.9 billion people in 2010. It will gain an additional 4 billion people by the middle of this century. History shows that when people have more money to spend on food, they want meat, he said.

"In Africa, if you become prosperous, what are you going to go and eat first? You are going to change from eating cassava," a root vegetable "which everybody hates, to having chicken or beef," he said. "That is going to happen. There is no way around it in spite of all of our efforts."

So, while some individuals push an optimistic agenda of eating less meat, Ray said that in order to close the growing gap between food supply and demand, efforts need to be focused on increasing crop yields in regions of the world where yields are currently improving too slowly.

Mapping the gap

He and colleagues from the Institute on the Environment based their research on the premise that global crop production must double by 2050 to meet projected demands from increasing population, diet trends toward more meat and dairy products and increasing biofuel consumption.

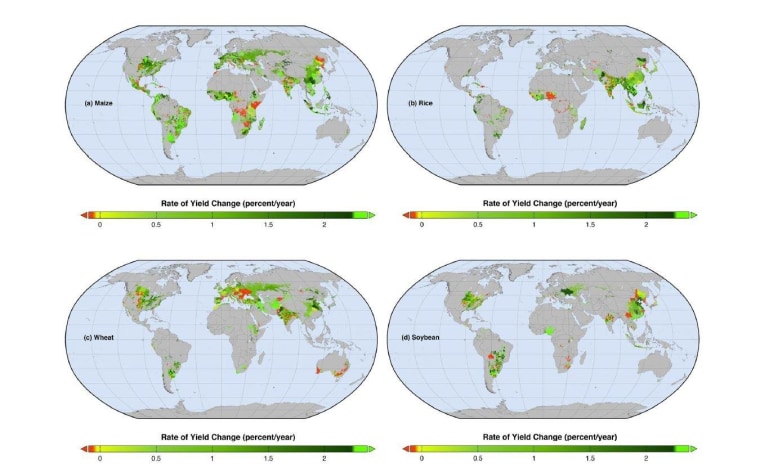

Globally, the team found that yields of four key crops — corn, rice, wheat and soybean — are increasing at rates between 0.9 and 1.6 percent a year, well below the needed 2.4 percent increase needed to double crop production by mid-century.

David Lobell, associate director of the Center for Food Security and the Environment at Stanford University, told NBC News in an email, that the institute's math adds up. "The global rates of yield increase are well known," he said.

What's new, Ray noted, is that his team divided the world up into 13,500 political units to provide a high-resolution map of where yield improvements are needed most. The results are published online today in the journal PLoS ONE.

"Now we have a better understanding of where exactly the problem is and where there is no problem," he said. For example, corn yields are increasing sufficiently in North Dakota to double by 2050, but yields are falling in Guatemala, a country where corn provides 36 percent of the dietary energy.

Boosting yields

To boost yields, Ray pointed to the work of "heroes working in the field in Africa," including those from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, to teach improved agricultural practices, such as when to plant crops and how to properly apply fertilizer.

"But it will take a long time," Ray noted. "You cannot change 1 million farmers in a particular African nation overnight to suddenly become smart farmers. This is a huge ship that has to be course-corrected."

The goal of his paper, he explained, is to help focus efforts on yield improvement, thus avoiding the conversion of forest and prairie lands to agricultural fields to meet the rising demand, which comes at a high cost to biodiversity and the global climate.

"Alternatively, additional strategies, particularly changing to more plant-based diets and reducing food waste can reduce the large expected demand growth in food," the team concludes in PLoS ONE.

John Roach is a contributing writer for NBC News. To learn more about him, visit his website.