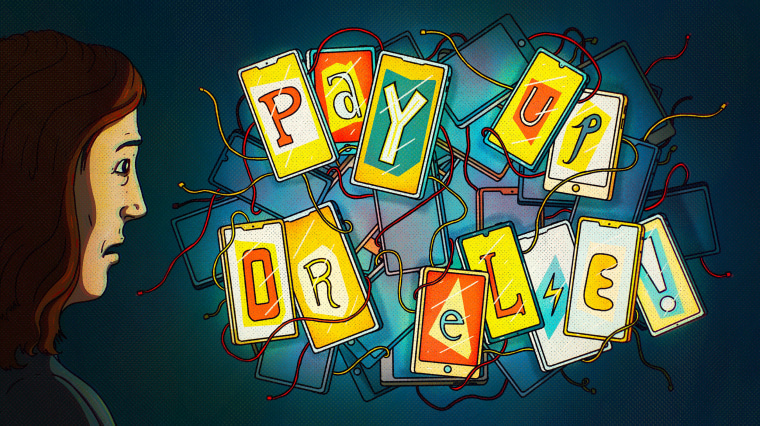

Wayne didn’t know his son’s school district had been hacked — its files stolen and computers locked up and held for ransom — until last fall when the hackers started emailing him directly with garbled threats.

“we hold control on the network several months, so we had a ton of time to carefully study, exfiltrate the data and prepare attack,” one of the three emails he received said. If his son’s district, the Allen Independent School District in the Dallas suburbs, didn’t pay up, all its files, including information on him and his son, “would be released in the dark market,” the emails warned.

It was a credible threat. Ransomware hackers frequently leak files of organizations that don’t meet their demands and have littered the dark web with school children’s personal information.

What Wayne received, however, represented a newer tactic. Ransomware hackers, always in search of new ways to add pressure to organizations they extort, have increasingly roped in everyday people whose information is stored in computers they hacked, pestering them by phone and email to lobby the victim organization to pay.

The hackers, who often work as loosely affiliated gangs with members in different countries, have made millions of dollars in recent years by attacking the computer networks of American companies, schools, hospitals and cities. Despite the Biden White House’s policies to slow the attacks, hackers were roughly as productive against U.S. targets last year as they were the previous two, successfully attacking more than 1,000 school districts and health care providers in 2021.

Wayne, who requested that NBC News withhold his last name to protect his family’s privacy, had heard of ransomware before. He wasn’t shocked to learn that the Allen School District, which oversees his son’s school, had become a victim when he started receiving those emails.

But he was furious that no one from the school district had contacted him, that he had to get the news directly from the hackers themselves.

“They didn’t give the parents or the staff any information,” Wayne said.

The school district didn’t respond to requests for comment. It eventually offered parents and students free credit monitoring services, Wayne said. But he wished he’d learned far sooner that his family’s data had been compromised.

“They told us nothing,” he said. “That’s the upsetting part, is that they could have told us from the start, ‘We were hacked, lock your data down.’ They didn’t do that.”

Such calls and emails from hackers can be an unnerving experience for regular people, said Kurtis Minder, the CEO of cybersecurity company GroupSense, which had several companies receive such calls last year.

“You’ve got to put yourself in the shoes of a normal citizen when you get a call like that from some foreign hacker,” he said. “It’s got to be the most bizarre experience. It’s got to be super unsettling."

Because the cybercrime ecosystem is so convoluted, practically every major ransomware gang has reached out to individuals like Wayne, said Meredith Griffanti, who does crisis communications work for the cybersecurity advisory company FTI Consulting.

“It’s become extremely common,” she said. “It’s almost as if they have an entire PR department of their operations solely devoted to that pressure tactic.”

The hackers will use whatever contact information they can find, such as employee directories or customer databases, to identify individuals they can pressure, she said.

“Which of course can be quite scary for those that don’t know this is going on or this attack has happened,” she said.

Sometimes, those tactics include cold-calling people who work for the organization that’s been hacked. Last July, a quick-thinking worker at a company in the United Kingdom was able to record such a phone call. Sophos, the cybersecurity firm that the company hired to deal with the incident, published the call.

It’s noteworthy that the caller made reference to Europe's General Data Protection Regulation, said Chester Wisniewski, a researcher at Sophos. Under the law, companies are responsible for safeguarding individuals’ private information, and can face heavy fines for not protecting it.

“They threatened that he might be fined for GDPR,” he said. “The person who received that voicemail was in finance, so he would know about GDPR rules.”

Many ransomware groups have made it part of their routine operations to publish a victim organization’s files to customized dark web sites if they don’t pay. But this newer tactic aims to exploit people’s fears that their personal information will be leaked, Wisniewski said.

“They customize the threat to the context of whom they’re contacting,” he said. “So, often, when Americans get called, ‘It’s we have your Social Security number, we have your direct deposit information from your bank, and if you don’t want this information made public, you really ought to be talking to your IT department.’”