It took two days for remote learning to make Molly Pascal's kids cry.

Their school's hourslong remote online program last spring prompted near-immediate complaints of headaches, irritability and fatigue from the siblings, then in the fourth and fifth grades. Pascal, who lives in Pittsburgh, said she was able to talk to her children's school and narrowed their days down to the four most critical classes, jettisoning the rest. The family is now reluctant to even put on a movie at night because of the increase in screen time.

Remote learning has been difficult for many children, but Pascal's were facing a particular challenge: At home, they almost never spent time in front of screens.

"I feel like it has just confirmed our values," Pascal said. "I can see how screen time hurts my children."

Versions of this negotiation played out across the U.S. in the spring as efforts to halt the spread of the coronavirus led state governments to order school and business shutdowns in all 50 states. Many school districts made the transition to remote learning – a test for even those families with the necessary hardware, internet connections and patience.

While many parents threw in the collective towel on limiting their kids' screen time, and experts generally supported that decision, screen-free families found themselves reconsidering their policies. With school fully remote, avoiding screens entirely wasn't possible without drastic measures, such as home-schooling.

Some families, like Pascal's, doubled down on their choices as a direct consequence of the screen time required by learning. Others, like Lydia Elle, a lifestyle influencer and single mom living in Los Angeles, significantly revised their parenting rules as in-person options for seeing family, maintaining social connections and entertainment nearly vanished overnight.

"My daughter is an only child. She does school online. All of my family lives no closer than 2,000 miles away," Elle said. Avoiding screen time beyond school would have cut her daughter off from her community during a highly stressful time, she said.

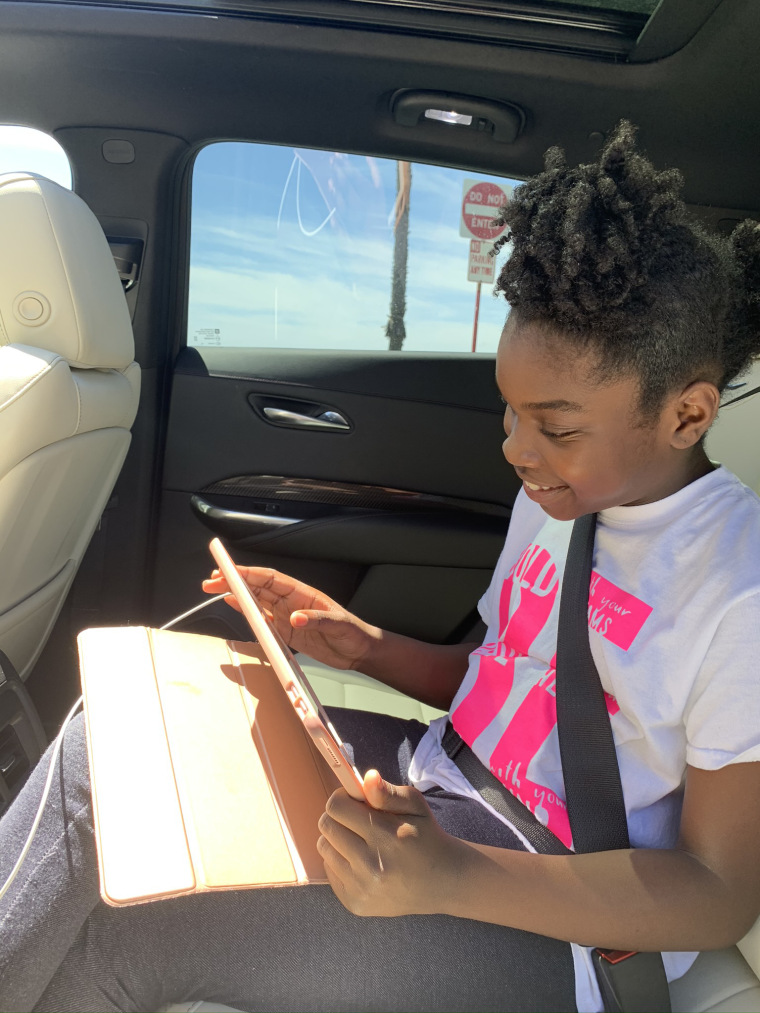

After her remote school day ends, Elle's 11-year-old daughter calls up a friend on FaceTime and they hang out, perhaps playing the popular computer game Roblox or chatting aimlessly.

"I decided not to infringe on her need to socialize in whatever ways she can carve it out," Elle said. "In another life, I'll be like, 'Oh, my goodness, that's terrible.'"

In recent years, experts have moved beyond recommending strict limits on children's screen time to focus more on how that time is being spent. In March, the American Academy of Pediatrics put out a statement eschewing formal screen time limits, suggesting only that families "preserve offline experiences" and acknowledging that "screen media use will likely increase."

Michael Robb, the senior director of research for Common Sense Media, a nonprofit that evaluates and researches digital media for children, said parents should work backward, making sure their kids have access to a range of important experiences over the course of a week. They should include playing with friends, being outside, getting a good night's sleep and nutritious food – some of which will involve screens.

Robb also highlighted the value of using digital media as a shared family experience, which other parents said they found valuable. Digital media, he said, can be a source of conversation and positive memories instead of a constant fount of tension and disagreement.

"Frankly, if it can be a source of joy for families to do something together, that's wonderful," Robb said.

Elle and her daughter have started watching "Gilmore Girls" together and have found it to be a bonding experience during a highly stressful time.

The pressures of remote learning eventually led at least one screen-free family to opt out of formal school altogether.

Meghan Owenz, an assistant teaching professor at Penn State Berks and co-founder of screenfreeparenting.com, said her children, ages 5 and 8, had a grueling remote schedule. Their school day ran from 8:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., with five hours of live instruction a day. She and her husband, who are both working from home, submitted alternative activities that corresponded to their kids' lessons for the day, and they told the school they wouldn't be present for live instruction.

Last week, they decided to formally unenroll their kids and home-school them, instead.

That was "essentially what we were doing anyways," Owenz wrote in an email. "Now, we just have less uploading to do."

Many parents, especially affluent ones, have pushed to shift kids' pre-pandemic activities online and carry on as normal, Owenz said in an interview. When Pascal's son's martial arts classes went online, her family gave them a try before realizing they were a poor substitute for the camaraderie and enjoyment that came from physically being in class.

"It's not the same, and kids aren't going to be as engaged," Owenz said. "Might it be OK to say, 'This is a really different time than it was last year, and we're going to do some really different things that maybe are interesting that we don't normally have time to do?'"