Timing is everything, especially to physicists seeking to unite the mechanics of gravity with the quantum world of particles.

So when the opportunity came to measure if gamma rays of different energies traveled at the same speed, a team of physicists stepped up to the challenge.

At stake was nothing less than a foundation of modern physics — Einstein's theory of relativity, which posits that all electromagnetic radiation travels at the same speed, whether low-energy radio waves, high-energy X-rays or gamma rays, or any wavelength in between.

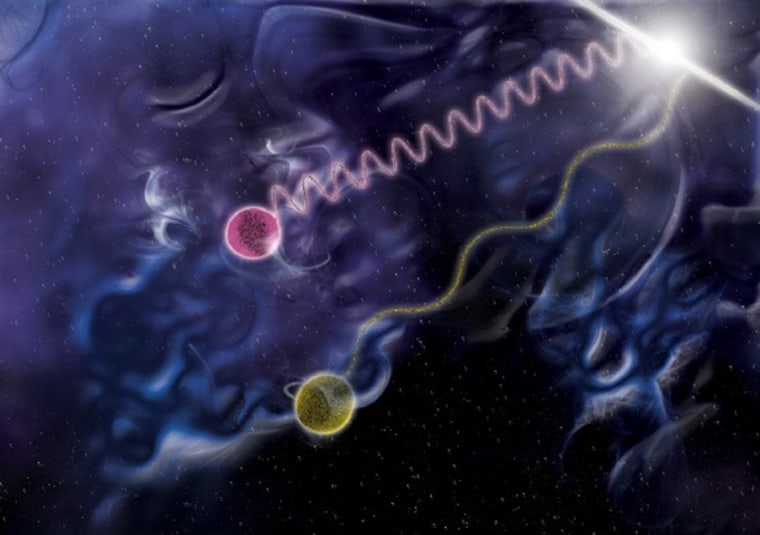

A violent explosion 7.8 billion light-years ago gave scientists the unique opportunity to punch a hole in Einstein's theory. NASA's Fermi Gamma Ray Telescope detected many gamma ray photons from the 2.1-second long burst, including one that was a million times more energetic than another.

Scientists wondered if the higher-energy photon might have arrived in the telescope's detector slightly later than its partner due to quantum-level entanglements in space that a less energetic photon wouldn't even notice.

"Some quantum gravity theories predict that the higher energy photons are more affected by the quantum nature of space-time and will travel more slowly than lower energy photons," said Stanford University's Peter Michelson, the lead scientist on the Fermi Large Area Telescope.

Michelson says it's kind of like the difference between a car and an ant traveling down a dirt road: The car isn't impacted by the pebbles and the rocks, whereas an ant has to go around every obstacle in its path.

After a journey of more than 7 billion light-years, however, the gamma ray photons arrived nine-tenths of a second apart on May 9, 2009 — not enough of a lag to account for the theorized quantum effects.

"Einstein, at this point, wins again," Michelson said.

That's not to say that a theory of quantum gravity doesn't exist.

"It's a theory that would unify all the forces of nature," said Mario Livio, an astrophysicist with the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

"What Fermi has done here is push us to our limit," he added. "This only tells us where are the dead ends. It doesn't necessarily tell us where the correct way is."

The research was presented during a three-day symposium in Washington D.C. to highlight results of the telescope's first year of operations.

More on: gamma rays