A European satellite has beamed home its first map of the entire sky as seen in microwave light, to the delight of astronomers hoping to catch a glimpse at the earliest days of the universe.

The new sky map from the Planck observatory is the most detailed microwave map of the sky and is a record of the oldest light in the universe, so it could have important ramifications for cosmology – including insights into the formation of the universe 13.7 billion years ago.

Scientists have eagerly awaited the data from Planck since the mission was launched by the European Space Agency in May 2009. The observatory has been meticulously scanning the heavens in microwave light, which has longer wavelengths (shorter frequencies) than visible light.

Mapping the entire sky

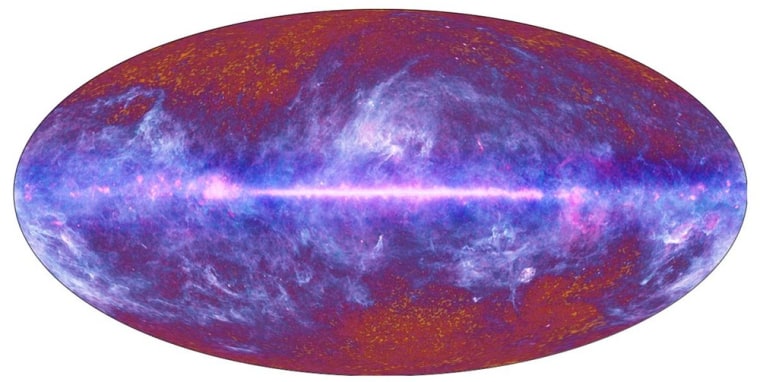

Planck's microwave sky map shows the main disk of the Milky Way where new stars shine brightly and streamers of cold dust reach above and below this belt.

The map also reveals light echoes — called the cosmic microwave background radiation — left over from the big bang thought to have created our universe. It can be seen in the mottled backdrop at the top and bottom of the image.

To get a full picture of this microwave background, researchers must digitally remove the Milky Way's light from the foreground to reveal the dimmer background radiation.

Planck's observations are the most precise view of the cosmic microwave background ever obtained. These data offer hope of settling some of the most vexing questions in cosmology, such as what happened immediately after the universe was formed, and whether we are stuck in a cycle between big bangs and big crunches due to repeat on loop.

"This is the moment that Planck was conceived for," said David Southwood, ESA director of science and robotic exploration, in a statement. "We're not giving the answer. We are opening the door to an Eldorado where scientists can seek the nuggets that will lead to deeper understanding of how our universe came to be and how it works now. The image itself and its remarkable quality is a tribute to the engineers who built and have operated Planck. Now the scientific harvest must begin."

Cosmic quandaries

One of the main quandaries scientists hope to tackle using Planck is whether the Big Bang was followed by a period of rapid expansion called inflation. Such an expansion would have doubled the size of the universe many times over during a period of time much, much shorter than one second.

The Planck satellite is slated to continue scanning the universe until 2012, building up an ever-more-detailed map of the sky.

"This image is just a glimpse of what Planck will ultimately see," said Jan Tauber, ESA's Planck project scientist.