Deborah Pierce held a rare and precious document in her hands. It was the story of her life, as told by ChoicePoint Inc. She wasn't supposed to see it; an anonymous source had smuggled the report to her. But there it was, her "National Comprehensive Report," 20 pages long, a complete dossier of all the digital breadcrumbs she's left behind during her adult life.

At least, that's what it was supposed to be.

Pierce said she felt an uneasy twinge in her stomach as she began to flip the pages. A dozen former addresses were listed, along with neighbors and their phone numbers. Almost 20 people were listed as relatives -- and their neighbors were listed, too. There were cars she supposedly owned, businesses she supposedly worked for.

But the more closely she looked, the more alarmed she became: The report was littered with mistakes.

ChoicePoint, the now embattled database giant, aggregates data from hundreds of sources on millions of Americans. The reports are then sold to thousands of companies and government agencies that want to know more about their clients, customers, or employees.

As first reported by MSNBC.com, the company last month warned 145,000 people that criminals posing as legitimate businesses had accessed that information, putting them at risk of identity theft. The incident sparked discussion about the larger industry of data collection, made up of companies known as commercial data brokers. ChoicePoint is the largest, but there are hundreds of other firms that collect and sell private information for profit. ChoicePoint also has a host of important government clients, including the FBI and other intelligence agencies.

The Alpharetta, Ga.-based company declined to be interviewed for this story, pointing a reporter toward the firm's Web site for additional information. The company separately announced Tuesday that it has hired a top official at the Transportation Security Administration to review how the company screens its customers.

Pierce, a privacy advocate, obtained her report nearly two years ago, long before the current controversy. Thanks to the unknown source -- perhaps a company employee, Pierce said, but she has no way of knowing -- she got a rare privilege most consumers don't: a chance to see what ChoicePoint knows about her.

She didn't like what she saw.

Glaring errors and omissions

What first caught Pierce's eye, she said, was a heading titled "possible Texas criminal history." A short paragraph suggested additional, "manual" research, because three Texas court records had been found that might be connected to her. "A manual search on PIERCE D.S." is recommended, it said.

Pierce says she's only visited Texas twice briefly, and never had any trouble with the law there.

"But if I was applying for a job, and there were other candidates, and this was on my record, the company would obviously go for another person," she said. "It raises a question in your mind."

It's not clear prospective employers would see that part of Pierce's file as part of an employment background check. The firm declined to answer specific questions about Pierce's report -- or to confirm its authenticity -- but said it was likely designed for law enforcement officials.

"It is ... only intended for trained investigators who use the information as a directional guide of where to go to confirm facts in the public record," said spokeswoman Kristen McCaughan. Internet searches indicate the reports are also sold to private investigators.

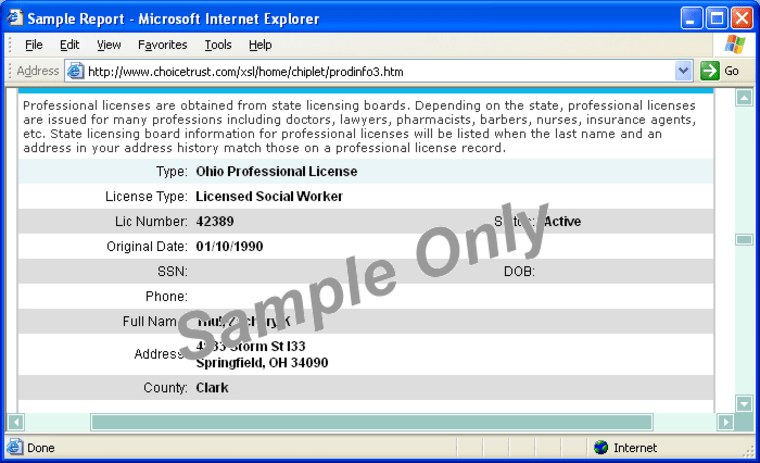

On ChoicePoint's Web site, the National Comprehensive Report is described as a collection of searches that glean data from "national and state databases for a summary of assets, driver licenses, professional licenses, real property, vehicles, and more. Each report offers the ability to add associates to the report, which include relatives, others linked to the same addresses as the subject and neighbors."

Knowing former addresses and neighbors — assuming such information was correct — would be of obvious utility to law enforcement officials investigating a crime.

But even if the report was only marketed to law enforcement, Pierce said she was still concerned about who might end up seeing the information. And there were many more inaccuracies that troubled her.

Under former addresses, an ex-boyfriend's address was listed. Pierce said she never lived there, and in fact, he moved into that house after they broke up. The report also listed three automobiles she never owned and three companies listed that she never owned or worked for.

Under the relatives section, her sister's ex-husband was listed. And there are seven other people listed as relatives who Pierce doesn't know.

"There are all these other people in my file. I find that offensive," she said.

Most alarming to Pierce is the fact that, with all this information, the ChoicePoint report she received had glaring omissions, too. Many of her former addresses aren't listed; and despite the host of other people listed on her report, many relatives and nearby neighbors were missing.

"I see my next door neighbor almost every day when I'm here. And he's not there," she said. "If you were going to do an investigation on me, he'd be the one you'd want to talk to, not the burrito place on the corner. ... It really makes you call into question the effectiveness of this kind of data collection."

His ChoicePoint report said he was dead

Pierce's experience neatly parallels that of Richard Smith, another privacy advocate, who paid a $20 fee and received a similar report from ChoicePoint several years ago. The company offers a wide variety of reports on individuals; Smith purchased a commercial version that's sold to curious consumers.

Smith's dossier had the same kind of errors that Pierce reported. His file also suggested a manual search of Texas court records was required, and listed him as connected to 30 businesses which he knew nothing about.

Some of the mistakes on Smith's report were comical: That his wife had a child three years before they were married, that he had been married previously to another woman, and most absurd, that he had died in 1976.

"Pretty obviously the data quality is low," Smith said.

He equated a ChoicePoint report to the results of a Google search on a person -- solid information is mixed in with dozens of unrelated items. The more common a name, the more extraneous information is produced.

"People who use this data should keep that in mind," Smith said.

Elizabeth Rosen has also spotted numerous mistakes in her seven-page ChoicePoint report. Rosen, a nurse from Los Angeles, Calif., was the first consumer to complain to MSNBC.com after receiving a letter from ChoicePoint in February indicating her personal information had been stolen.

Rosen has since received a copy of one of her ChoicePoint reports, a "personal public records search," -- she's still awaiting others -- and already, she's spotted a series of mistakes.

"There are problems on five of the seven pages," she said.

The most serious involve two post office boxes she has owned, one in Florida and one in Texas. She only held the boxes for a short while, but Rosen believes she's now been connected to every other firm that has rented those boxes. In Miami Beach, she is listed as the owner of a firm named Adopt-A-Classroom. In Texas, she's been tied to a nail salon, a deli, and a firm named Phoenix Investigations, among 44 other businesses. She is also listed as an officer of a firm named "Reimbursement Specialists Of Central Texas, LLC."

No way to fix errors

But what really bothers Rosen is what happened next.

"I asked the guy at ChoicePoint how I can get these errors fixed," she said. "And he said they can't."

Rosen was told she had to talk with each furnisher of the information individually -- to the private firm where she rented the P.O. box, for example -- and convince each one to update their information and then send it back to ChoicePoint. Rosen figures there might be 100 different sources of information in her report, so fixing the errors would be just about impossible.

"I told them, 'I don't want to be spending 40 hours a week correcting your errors,’" she said.

The ChoicePoint data leak has sparked calls for congressional investigations and new legislation. One bill, proposed by Florida Sen. Bill Nelson, would place companies like ChoicePoint in the same category as credit reporting agencies, which are governed by the Fair Credit Reporting Act and its subsequent revisions. That law establishes detailed -- albeit imperfect -- procedures for correcting errors in personal information.

That's a start, Pierce said. But fundamentally, she thinks lawmakers and corporations need to give more consideration to the compilation and use of such reports in the first place.

"Why are they entitled to have this information? How useful is it, if it's not accurate?" Pierce said.

Meanwhile, Smith said compliance with such an accuracy requirement may be much easier said than done. Companies like ChoicePoint, which has gobbled up dozens of smaller database firms in recent years, often have hundreds of different databases. The data is often in very different formats, and not linked in any way. Simply answering the question "What's in my file?" may be impossible.

"There's no business reason for them to do it," Smith said. "Still, it would be nice if you could pay them ... and just ask, what do you know about me?"

Currently, consumers can order various fee-based reports at ChoiceTrust.com, ChoicePoint's consumer Web site. A list of consumer products is available at .

Bob Sullivan is author of Your Evil Twin: Behind the Identity Theft Epidemic.