Growing up, Shannen Kim had to get good grades — no ifs, ands or buts.

“It was always just a given, like work hard now and get into a good college,” Kim, 24, recalled. “That’ll make me successful and that’ll make me happier in the end.”

Kim got into that “good” college — Harvard — but then came her first midterm. She received a D.

Devastation set in.

“I think so much of my self-worth and value was so closely tied to my accomplishments, and my academic accomplishments, it was like an attack on my identity and who I thought I was,” Kim, who is half-Filipino and half-Korean, said.

WATCH: 'A for Average, B for Bad' - an NBC Asian America short documentary from Jubilee Media

The stereotype of the “studious Asian American” who excels academically, often in math and science, has long been entrenched in the ethos of the American education system. As the characterization goes, Asians do well because they’re part of a group of naturally high achievers who are highly educated and highly successful, a model to which other racial minorities should aspire.

But even as detailed data on education and income across the diverse Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) spectrum has begun debunking this myth, experts say the stereotype still persists.

For many young AAPIs, it means always rising to meet an academic bar that seems to perpetually move upward — or being afraid to ask for help in school because the model minority label suggests you don’t need it.

That, experts say, can create additional pressures and lead to mental health issues.

“It’s like you’re supposed to be performing well so you don’t need help. So then when I needed help, I felt like I couldn’t go and ask.”

“Usually the model minority [label] does cause a lot of anxiety in a lot of the second-generation children,” Shanni Liang, a counselor for a mental health hotline in New York City, told NBC News. “We do get a lot of callers that have their first mental health breakdown in college.”

Originating in the 1960s, the term “model minority” at first applied primarily to people of Chinese and Japanese descent, the two largest Asian ethnic groups in the United States at the time, according to Karthick Ramakrishnan, a public policy professor at the University of California, Riverside.

“[It was] not just the notion that all Asian Americans are successful or high skilled or high income, but also to contrast Asian Americans with African Americans and to hold Asian Americans up as models,” Ramakrishnan told NBC News.

During the ’60s, a decade that saw the modern civil rights movement take shape, African Americans were protesting and agitating for change, Ramakrishnan said, leading to contrasts between blacks and Asian Americans and the latter’s apparent successes.

“‘Instead of complaining and protesting, why can’t they succeed in the same way?’” Ramakrishnan said, describing the prevailing mindset. “That was the model minority myth.”

Ramakrishnan calls it a myth because he says it failed to account for how the experiences of Asian Americans in the ’60s were “so different [than those] of African Americans, Native Americans, or even many Latinos, who were either slaves or had their lands colonized by the United States.”

But it’s not just those outside the AAPI community who perpetuate the model minority label.

“There are many Asian Americans who think that Asians might be naturally smarter, or there’s something about Asian culture that makes them truly exceptional, unlike other minority groups like blacks and Latinos,” Ramakrishnan said.

Those expectations, experts say, can have negative consequences.

“The averages look really good in terms of educational achievement or income. But in fact those averages mask a lot of differences.”

Liang, the mental health hotline counselor, said she handles a lot of calls involving academic pressure from New York’s Chinese population, which is the largest of any city outside of Asia, according to the New York City Department of Planning.

“They’re under a lot of stress because their parents sacrificed a lot and they’re trying to keep up their grades,” Liang said. “And they do go through a lot of anxiety where they have to leave school after the first year.”

“Parents are overworked,” she added, saying they don’t give a lot of attention to their children because of the long hours they work as immigrants.

“So really the only validation they get is from good grades,” Liang said. “That becomes their identity, just to get approval from their parents.”

Liang said she has also seen this pattern play out among students of Korean, Indian, and Japanese descent in New York City.

Today, as U.S. immigration patterns have shifted, the model minority label has also been applied to other AAPI groups, including Southeast and South Asians. This phenomenon, what Ramakrishnan calls “model minority framing,” presents its own host of problems.

“It’s kind of a statistical sleight of hand, if you will, a statistical misunderstanding that people think all Asians do well in math, because the average Asian American does well in math, or all Asians are high skilled, because the average Asian American is high skilled,” he explained.

“The averages look really good in terms of educational achievement or income,” Ramakrishnan said. “But in fact those averages mask a lot of differences.”

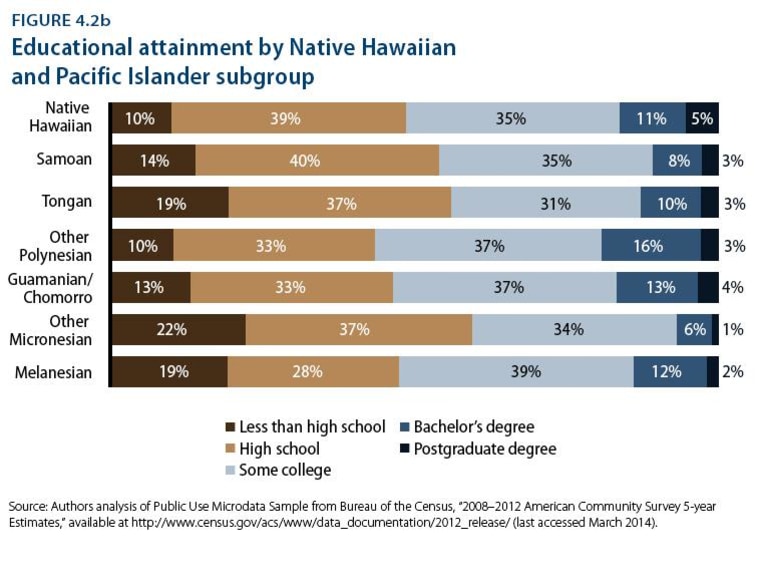

Southeast Asians are one group that often gets lost in the numbers. Take education, for instance. Cambodians, Laotians, and Hmongs all place at the bottom for degree attainment, according to AAPI Data, a project Ramakrishnan started. For those three groups, less than 1 in 5 have a bachelor’s degree or higher, the figures show.

Contrast that with Taiwanese and Asian Indians, of which roughly 3 in 4 have at least a bachelor’s degree, according to the data.

For Nkauj Iab Yang, who is Hmong, the model minority label wasn’t something she consciously knew growing up in a low-income neighborhood in Sacramento, California.

“But then you do notice that you’re treated a little bit differently as a Southeast Asian young person who’s going through the K-12 system, where maybe your teachers are not paying as much attention to you,” she told NBC News.

"The model minority [label] does cause a lot of anxiety in a lot of the second-generation children."

Yang, now the director of California policy and programs for the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center (SEARAC), a national advocacy group, said she believes teachers and her school district naturally expected her to do well because she is Asian American.

Those expectations proved problematic, Yang said, because she needed tutoring in high school.

“It’s like you’re supposed to be performing well so you don’t need help,” she said. “So then when I needed help, I felt like I couldn’t go and ask.”

“I feel like a lot of Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders still face that barrier,” Yang added.

There’s also the issue of providing mental health services for Southeast Asian students.

“The experiences of trauma either for themselves or their parents will play a significant role in terms of what their high school experience will be like,” Ramakrishnan said.

That, he said, derives from the general wartime experience of being refugees, seeing villages destroyed or relatives killed before their eyes.

RELATED: Why Data Matters When It Comes to Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and Education

Since 1975, over 1.2 million refugees fled war in Southeast Asia and resettled in America, making them the largest refugee group in U.S. history.

Looking back, Yang said she believes she needed mental health services because of trauma she inherited from her parents, both of them refugees from Laos.

“But nobody knew to even identify that,” she said.

Also feeling the pressures of the model minority label are South Asians, a group that includes people of Indian, Bangladeshi, and Pakistani descent, among others.

“It is absolutely not just a myth, but really a farce, that all South Asians are part of a model minority that are across the board prospering,” Suman Raghunathan, executive director of South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT), a national civil rights nonprofit, told NBC News.

Similar to the figures on Southeast Asians, data on education attainment for South Asians also expose disparities within that group.

While 74 percent of Asian Indians have a bachelor’s degree or higher, for instance, only 48 percent of Bangladeshis achieved the same, according to figures from AAPI Data. In between are Pakistanis at 53 percent.

South Asians also deal with another kind of stress in school, civil rights advocates say.

“I think I might have been conditioned into this idea, from my family as well as from people at school, that being of Indian background we have this natural focus on math and science."

“We have a number of South Asian youths, be they in primary or secondary school, who are also being told to go back home or are being told by their peers that the government will build a wall and that they won’t be able to come back home,” Raghunathan said.

Ramakrishnan said a lot of this rhetoric stems from anti-Muslim sentiment following the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks — even though not all South Asians are Muslim.

“It shows you the fallacy of thinking that the Asian experience is the same for every group,” he said.

While parents’ expectations can be a source of academic pressure for some AAPI students, 20-year-old Nikhil Mandalaparthy experienced something different.

“For most of high school, [my parents] were the ones telling me not to be so stressed,” Mandalaparthy, an undergraduate at the University of Chicago double majoring in public policy and South Asian studies, told NBC News. “I was pretty lucky in that sense.”

RELATED: 50 Years Later, Challenging the ‘Model Minority Myth’ Through #ReModelMinority

Mandalaparthy grew up in Seattle, Washington, and was one of very few South Asian kids in school, he said. His mom and dad, both with master’s degrees, are immigrants from South India.

“I think I might have been conditioned into this idea, from my family as well as from people at school, that being of Indian background we have this natural focus on math and science,” said Mandalaparthy, a 2016 alumni of SAALT’s Young Leaders Institute.

It wasn’t until high school, Mandalaparthy added, that he became conscious of the model minority concept.

“I think that, especially when I was younger, I accepted this narrative without questioning it,” he said.

The model minority label, Mandalaparthy said, did in fact describe his family’s circle of friends and other Indian kids he met at school.

“Everyone was very successful — someone working in Microsoft or a doctor or engineer,” he said.

But as he learned more, he said he saw how the label marginalizes others, including undocumented South Asians.

“I think I’ve really unlearned a lot of the narrative in the past few years,” Mandalaparthy said.

In an effort to fight back against the model minority myth — and the social and academic pressures that stem from it — some community organizers, nonprofits, and researchers have turned to data in order to break down the numbers by ethnicity, a process known as disaggregation, to see how experiences vary across the AAPI spectrum. Doing so, they argue, can better target resources among AAPIs while dismantling the model minority myth.

But disaggregation also has its critics. Some in the AAPI community, many of them Chinese, have protested recent laws in states like California and Rhode Island, which require certain AAPI data on healthcare and education to be categorized by ethnicity.

Opponents have asked why the legislation applies only to AAPIs and worry that it may be used to advance race-based policies.

Meanwhile, mental health practitioners like Liang continue their work to help young people cope with academic pressures.

She said many crises can be prevented if AAPIs learn early on how to deal with the stress of high expectations of getting good grades and if they seek professional help.

But that isn’t so easy, Liang noted. Some have difficulty accessing mental health therapy because of language barriers or health insurance reasons, she said.

“There is [also] a cultural stigma, like people who get mental health care means they’re crazy,” Liang added.

Liang said the first step is asking for help, such as at a college counseling center. But with the model minority label, she added, taking that very first step is often the most difficult.

“Sometimes, it’s just as simple as reaching out and telling your friend, and then your friend getting help for you,” Liang said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.