When Erlin Gomez saw police officers in front of his apartment complex on the afternoon of Sept. 11, 2013, he parked his car and considered his options.

Gomez suspected the cluster of cops and unmarked cars blocking the gate to the heavily Latino complex was a checkpoint, designed to catch undocumented immigrants. In Jefferson Parish, a county just outside New Orleans, such encounters with local police and federal immigration agents had become common, according to Gomez and many in the growing immigrant community.

But Gomez, a 28-year-old undocumented immigrant from Honduras who arrived in Louisiana in 2006, had to take his chances.

Gomez got out of his car and walked toward the gate. A police officer intercepted him and asked for his ID and apartment number. "I said I didn't want to tell him," recalled Gomez, who’d already been deported once.

The officer responded by slipping handcuffs around Gomez’s wrists. Then another man, who Gomez learned was a federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent, brought him to a vehicle. Inside sat a small fingerprinting device that would instantly check his fingerprints against multiple biometric databases.

A single scan of his finger landed Gomez in a federal detention center, and he’s now awaiting word on whether he’ll be deported. But his encounter inside the vehicle would otherwise leave no traces -- no record of his arrest, or of why officers stopped him, and no proof, other than his memories, that officers from two agencies had set up a checkpoint in a suburban parking lot.

Deportations, which doubled under President Bush, have risen again under the Obama administration to historic highs, with 409,849 removals nationwide in 2012. Gomez is one of thousands of immigrants across the country who’ve been snared in a surge fed by partnerships between local and federal officials who use biometric tools to find deportable aliens.

But critics say that Jefferson Parish is a prime example of how such partnerships and tools have led to widespread abuses. Civil libertarians and advocates for immigrants charge that Latinos, including legal residents, are being stopped for dubious reasons and their biometric data collected, and that the drive to catch criminal aliens is leading to the deportation of long-term residents without criminal records and with deep ties to the U.S.

Since 2008, Jefferson Parish has led the nation in deportations of immigrants without significant criminal records. From 2008 to 2011, 87 percent of those deported after an arrest in Jefferson Parish had no prior criminal convictions, or were convicted of crimes resulting in sentences of less than a year, the highest percentage in the U.S.

“This law enforcement technology is rolled out in communities where people can’t push back,” said Jennifer Lynch, staff attorney for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil liberties advocacy group, and author of a report on the use of biometric data in immigration enforcement.

But while critics say too little attention has been paid to the potential for abuse, others argue that biometric devices aid both police agencies and the suspects they detain.

Follow NBC News Investigations on Twitter and Facebook

“Rather than fostering discrimination it makes sure that people are going to be identified properly,” said Jessica Vaughan, director of policy studies at the Center for Immigration Studies, a policy research group that advocates limiting immigration. “After all, it doesn’t come into play unless an officer has made a legitimate stop to begin with.”

100 million records

Erlin Gomez was stopped and identified as a “criminal alien” because of the confluence of two trends: a broader definition of which immigrants are considered “criminal aliens,” and the spread of technology that makes it easy for law enforcement to identify those aliens.

ICE’s use of biometric tools is not new. The agency and its predecessor, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), have used fingerprint checks and gathered biometric data since the 1990s.

But today, ICE agents equipped with handheld devices, some as small as an iPhone, can check an individual’s fingerprints against federal databases and have results in minutes. The Department of Homeland Security’s IDENT database, for example, contains 100 million records.

ICE’s targeting of “criminal aliens” for deportation is also not new. But the definition of that term has widened significantly in the past two decades, as have criminal prosecutions for immigration violations. Immigrants who are deported but then return, like Gomez, are now increasingly charged with “illegal re-entry,” a federal felony.

In 2011 the agency announced it would focus on deporting violent or convicted criminals, and immigrants who posed a threat to national security. The new targets included returned deportees, as well as “immigrant fugitives,” meaning immigrants who failed to appear for a court date. In 2012, ICE launched a program called the Criminal Alien Removal Initiative, or CARI, to capture those targets.

ICE found willing partners for its deportation strategy in local law enforcement agencies, many of which had their own handheld biometric devices with instant access to databases. Across the country, federal agents have joined with local police departments to find and deport “criminal aliens.”

Some partnerships with ICE are unofficial, like the cooperation between the agency and the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office, and revealed via court documents and FOIA requests. Others, including task forces in various border communities, are official and public. Police departments in the San Diego area, for example, share facial recognition data with ICE as part of a county-wide program. And under ICE’s “Secure Communities” program, every locality in the U.S. is required to ship arrest data on criminal defendants to the feds to check for immigration offenses.

But even the officials who oversee ICE have expressed worries that the local police will misuse their access to biometric data. According to a 2010 memo obtained by immigration activists via the Freedom of Information Act, officials from the Privacy office of the Department of Homeland Security, the parent agency of ICE, had “concerns” that if access to the federal IDENT database was expanded, local police could “misuse” the information and engage in “profiling.”

“They believe that LE (law enforcement] Officers would be able to phish for information contained within IDENT,” said the memo.

Raul Pinto, staff attorney for the North Carolina chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, charges that those predictions of racial profiling came true in his state, where he says both undocumented immigrants and legal residents were detained at traffic checkpoints.

“We saw local law enforcement agencies stopping people who look Latino because they think they may be undocumented and fit the profile that the ICE fugitive ops are looking for,” Pinto said. “That runs afoul of constitutional protections. A violation of the Fourth Amendment is a violation of your civil rights, whether you’re undocumented or not.”

Immigrants and advocates say the same pattern of high-tech profiling appeared in Southern Louisiana. Jacinta Gonzalez of the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice, an immigrant rights group, said that both non-citizens and citizens have complained to her office about stops and arrests.

She said immigrants have described being asked for ID, then handcuffed and fingerprinted, while walking on the street, standing in their front yard, or driving through checkpoints. Hispanic U.S. citizens, she said, have also reported being fingerprinted by ICE agents, then let go, after the scans of their prints show their legal status.

“They really are just casting a wide net, stopping and handcuffing and fingerprinting any people they come into contact with,” she said.

‘I told them I wasn’t a criminal’

In 2006, at age 21, Erlin Gomez made his first attempt to cross the U.S. border. But Border Protection officers caught him in Texas and he was deported back to Honduras.

Within days, he headed north again, and on his second try he made it to New Orleans.

The city's effort to rebuild after Hurricane Katrina was drawing migrant workers from Mexico and Central America. Gomez quickly found construction work. He and his wife had a son, now two years old and a U.S. citizen.

"People focus on the fact that we don't have papers,” Gomez said. “But we came to serve the country.”

Gomez and his wife settled in Jefferson Parish, just west of New Orleans, part of a wave of Hispanic immigrants moving into the county. According to census data, even as the county’s population decreased between 2000 and 2010 because of Katrina, its Latino population doubled. There are now at least 65,000 Latinos in Jefferson Parish, or 15 percent of the county’s population of 435,000.

According to the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office, that growing Hispanic population led to the need for a partnership between ICE agents and local officers.

While no official agreement exists between the two agencies, according to Col. John Fortunato, public information officer for the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office, ICE agents assisted police officers with “investigatory stops,” conducted “based on reasonable suspicion and/or probable cause.”

Fortunato said that the sheriff’s office asked ICE to patrol with police officers because of a rising crime rate involving Hispanic perpetrators and victims. Fortunato could not provide statistics indicating an increased crime rate among Latino residents, but statistics available on the county website show that overall crime has largely decreased in recent years.

On the afternoon of Sept. 11, 2013, the cooperation between the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office and ICE meant that there were officers from both agencies and a mobile fingerprinting lab outside Erlin Gomez’s apartment complex.

Fortunato denied that the presence constituted a checkpoint, or that the sheriff’s department ever set up checkpoints with ICE. “We don’t do checkpoints,” he said.

But internal ICE emails uncovered via FOIA by the North Carolina ACLU show that ICE has used the word “checkpoint” to describe its work with local law enforcement agencies in searching for deportable immigrants. A memo describing operations in the Southeast talks about local police being deployed at the “checkpoint,” looking for DWI and traffic offenses, with ICE set up at a “secondary location” ready to run fingerprints.

When Gomez placed his finger against the small screen of the fingerprint machine, it told the ICE agent manning the device that while Gomez had no criminal history except a previous arrest for driving without a license, he had an outstanding deportation order. That classified him as an “absconder,” one of ICE’s high-priority enforcement categories.

"They told me I was arrested because they were looking for criminals," Gomez said. "I told them I wasn't a criminal.”

In Jefferson Parish, the ad hoc collaboration between the locals and the feds has made it difficult to determine why some Latinos have been stopped and questioned by police. The ICE agents who scanned Gomez’s fingerprints were members of a CARI program “fugitive team.” Federal indictments from stops in the county describe the CARI team members “assisting” sheriff’s officers on “routine patrols.”

An ICE spokesperson told NBC News that nationwide, CARI teams target individuals using intelligence gleaned from local and federal sources, and do not fingerprint individuals without reasonable suspicion or probable cause. “ICE does not conduct sweeps or raids to target undocumented immigrants indiscriminately,” said Bryan Cox. He also said that to his knowledge the unofficial partnership between the CARI fugitive teams and the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office was the only such partnership in the nation.

According to ICE, Gomez was first arrested by Jefferson Parish officers, and then fingerprinted by ICE after officers asked the agency to check his immigration status. Cox said that immigrants must first be arrested before they are fingerprinted.

But agency documents obtained via FOIA indicate that ICE has for years tried to facilitate the sharing of biometric data with local law enforcement in “pre-arrest” scenarios, much like what happened to Gomez.The Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office told NBC News that it had no record of Gomez ever being arrested, and could not confirm what police officers were doing in front of his apartment.

What is known is that after ICE ran Gomez’s fingerprints, Gomez was taken into federal custody and shipped to a detention center in Basile, La.

According to ICE, most people fingerprinted by its mobile labs don’t wind up in detention centers. Agents from the New Orleans field office work in five states, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Tennessee, and release 75 percent of the people they fingerprint, said Cox. The agency couldn’t provide the total number of individuals fingerprinted, however, or a time frame for the 75 percent figure.

Biometric tools, said Cox, help agents make on-the-spot decisions about whether an individual should be processed for deportation. “The strategy,” he said, “is working.” In 2013, according to recently released numbers, 48 percent of those removed had been convicted of aggravated felonies, and 60 percent were either “immigrant fugitives” or had previously been deported.

Critics argue that while many perpetrators of serious crimes have been deported, the pool of priority cases is shrinking, which explains why the total number of removals fell from 2012 to 2013. The majority of those targeted now -- people with re-entry convictions or outstanding deportation orders – have typically spent many years in the U.S. without incident, working and raising families.

“A lot of their priorities have to do with people who have prior deportation orders, who ironically are people who have the strongest ties to this country,” said Jessica Karp, an attorney with the National Day Laborer Organizing Network. “The people that come back often have family here.”

Following protests by immigrants and advocates in New Orleans, and inquiries by NBC News, ICE said CARI teams have stopped going into the field alongside local law enforcement.

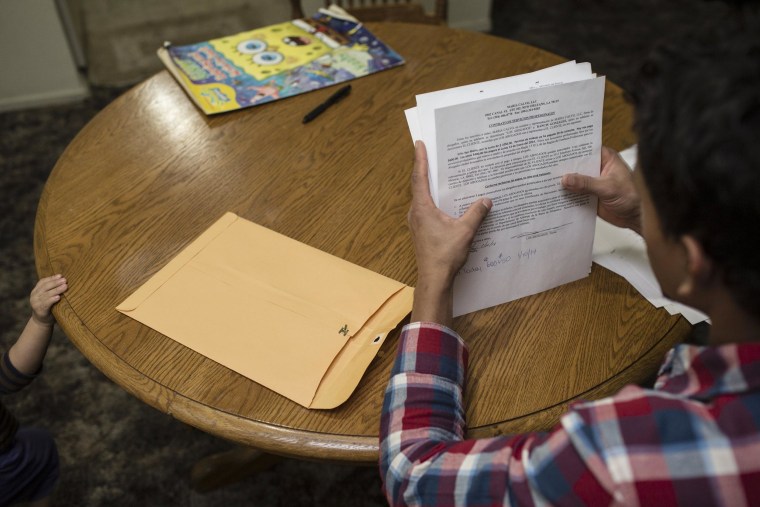

Gomez, meanwhile, was released after a month. The deportation order still stands, but because he has no underlying criminal conviction, he is a candidate for prosecutorial discretion. His case is pending, and he is hopeful.

“I want the opportunity to stay here with my son,” he said.