LONDON — Fleeing war or persecution and with dreams of new lives, they make perilous journeys to reach the sanctuary of the United Kingdom. But instead of finding the promised land they imagined, many asylum seekers who ended up as prisoners of Britain's immigration system say they wish they had never left their homes.

Each year thousands of asylum seekers are detained by authorities who do not believe their stories. Those who are not imprisoned in detention centers are banned from working and forced to live on welfare checks of just $56 per week. Some are stuck in limbo for years before government officials rule on whether they can stay.

The full extent of the chaos was revealed last week when British lawmakers revealed a "deeply worrying" and "disturbing" backlog of 29,000 cases where people have been waiting seven years or longer for their applications to be resolved.

Campaigners and some immigration lawyers allege the system is broken and fails the U.K.'s basic commitment to human rights.

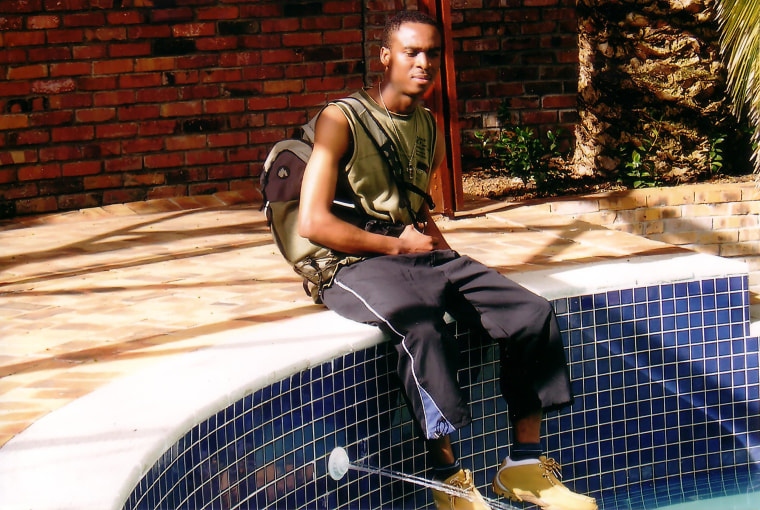

"Sometimes I wish I never came," said Jack Monday Ikegwu, a gay Nigerian who escaped to Britain. "You go through trauma when you come here to seek asylum, thinking you are going to be free, but the process in the U.K. was appalling."

With homosexuality illegal in Nigeria, Ikegwu managed to evade police who issued a warrant for his arrest when he was just 16. But he was later beaten, tortured and left for dead by a group of men.

He managed to escape his country of birth in February 2006 and flew to the U.K. in the hope of a new start in a tolerant society.

"What I experienced was worse than the torture I fled"

Authorities did not believe Ikegwu's story or that he was just 16 and he was held for 11 months in immigration detention centers across England. The most recent government figures showed 3,079 people were incarcerated in such facilities at the end of June.

"I was thinking, 'I have not done anything, I have not committed a crime,'" Ikegwu said of his time in detention. "They looked me in the eyes and said, 'We do not believe that you are gay.' I got very angry and felt a lot of trauma. I got panic attacks now and then, and I still get them today." According to Ikegwu, his case was only resolved after going into a relationship with a man he did not love just to prove he was gay.

Ikegwu's case was approved after five years, but thousands of others are forced to wait longer.

Britain's immigration laws mean even people who are not imprisoned must lead severely restricted lives. While their rent is covered, single asylum seekers awaiting a decision on their applications are not allowed to work and receive the equivalent of just $56 dollars per week. The sum is boosted by no more than $22 weekly for single parents who have a young child. This money is kept on a card that cannot carry over more than $8 per week — so saving is not an option. The card can only be used in selected stores and for goods the government deems essential.

"I have clients who cannot afford to get a haircut, or they cannot afford to buy a bus ticket to come and see me," said London-based immigration lawyer Tori Sicher, who worked with Ikegwu's case before it was resolved in 2011. "For everyone it's traumatic, and most of the time they have gone through even more traumatic things in their own countries, whether it's a war zone or a victim of trafficking who has been sold into the sex trade."

Leaving their families and homes behind in countries cleft by conflict and persecution, more than 23,500 people applied last year for asylum in the U.K. — which has a population of around 64.1 million. More than two-thirds of those who applied for asylum had their applications refused before appeal, according to government figures. But that is only half the story: The wait before the decision is often far worse.

"You come into this country and you’re treated like a criminal"

Abdal Mohammad says he was tortured by his own government in Sudan after participating in peaceful protests. At 19, he flew to London to escape further persecution. What followed was an 11-year ordeal in which he was imprisoned in every detention center in England, hauled in front of six judges, and ultimately left in a state of such despondency that he made several attempts to take his own life.

"The first thing in my head when I came here was that I was going to a safe haven," he told NBC News in an emotional interview by telephone. "The history of the United Kingdom, an understanding country, a defender of human rights and a protector of people, made me want to come here. But what I experienced was worse than the torture I fled."

Despite showing officials at London’s Heathrow Airport the 263 scars on his body, Mohammad said he was detained almost immediately. "There was no reason given," he said. "They took me to a prison, a detention center. I just couldn't work out what was going on. I was going through it in my head at the time, like, 'What the hell is happening to me?'"

Mohammad 's imprisonment was the start of a bureaucratic nightmare in which he was bounced between immigration officials, the courts, and medical officials. His last stint in detention was four years, ending only in July after the campaign group Medical Justice presented a report to a High Court judge confirming Mohammad had been tortured.

"I have never committed a crime and yet I was imprisoned for years," he said. "You come into this country and you’re treated like a criminal, or worse than a criminal."

Mohammad is still waiting for a decision on his asylum claim. At 31, he describes himself as a broken man. He has been placed with other asylum seekers, all strangers, in a shared house in Middlesborough, a town 250 miles from London in England’s industrial northeast.

Mohammad lists his current indignities with almost more anger than when he talks about his terms in detention: He cannot work, and he has been fitted with an electronic tag around his ankle; his $56 per week payment card is not enough to buy winter clothes nor halal meat, a religious necessity; and he said he is taking 17 medications per day for post-traumatic stress and various anxiety-related conditions.

"It makes you feel like the worst human being alive in the world," he said. "I am ashamed to leave the house. If you gave me the choice now between the physical torture and this, I would choose the physical torture again and again. Since I have been released I have tried to take my own life several times. The last time — three months ago — I had to go to the hospital because I tried to hang myself."

While Mohammad's detention was longer than most, lengthy detentions are not uncommon. "When you make your asylum claim you have a screening interview, which is a very quick assessment to find out where the person is from and what they are fleeing from," according to Ben du Preez, campaigns and communications officer at the London-based activist group Detention Action. "But these interviews take place often in an environment which is not conducive to talking about torture, or rape, or being gay, for example. If you are fleeing from a government that has tortured you and you are confronted by more men in uniform, disclosing that trauma can be an extremely difficult process."

The fact Britain is an island is a key reason why the country gets roughly one-sixth of the asylum applications of European economic powerhouse Germany. And having to cross the English Channel from France means migrants must find ways to enter the country using clandestine methods.

Eyob Kifle, 30, fled Sudan illegally on foot last year because he faced persecution as a Christian both there and in his original home of Eritrea. After paying a "businessman" $2,000, a four-month journey took him across the desert of Libya and the Mediterranean Sea in a boat crowded with 150 others. He arrived in the French port of Calais, where thousands of migrants are currently camped, and there he stowed away in the back of a truck with a dozen other people to cross the water to England.

Hours later, a knock on the side of the trailer from the driver told him he had arrived, although he was not initially sure where. "They just drop you in the middle of the road in London," he said. "I asked the first person I saw, ‘What city are we in?’ He almost laughed and told me I was in London."

His experience is similar to Dania, a 29-year-old woman who fled the violence of the Syrian capital of Damascus in 2012. "To apply for asylum here was very difficult because I did not know anything about it, " said Dania, who asked NBC News not to use her full name. "Once I found where to apply the officials said, 'Who's your legal support?' and, 'Who's your lawyer?' I did not even know I needed any of these things."

After asking around, Kifle learned that in order to register as an asylum seeker he needed to travel to Croydon in South London. His destination would be Lunar House, the asylum screening center through which every applicant not processed at the border must pass. A colossal piece of post-war brutalist architecture, the building serves as a daunting welcome to Britain.

By the time Kifle arrived it was after 5 p.m. and the front door was closed. A security guard told him to come back in the morning so he was forced to spend the December night sleeping in a churchyard. Ruth, an Ethiopian woman who spoke to NBC News’ U.K. partner ITV News last week, said she also had to sleep outside the building after arriving late. "It was freezing," said Ruth, whose name has been changed after she fled her home for political reasons.

Ghada Rasheed, 35, fled Iraq at the height of the post-war violence in 2007. She did not want to relive her traumatic journey to the U.K. other than to say "it was very exhausting and difficult" and admitted she struggled with "the guilt of leaving your family behind."

She added: "You feel like you are coming to the U.K. because it is your chance to live again but I felt like the people behind the glass were not interested in what I had to say. They just wanted to get the job done and go home."

It took her two years and several court battles to win her case. But the limbo of the interim period was excruciating, she said. "You basically just wait and wait, doing nothing, absolutely nothing. You feel like a burden on yourself and everyone else."

"All I do is wake up, watch TV, smoke, drink, and go back to bed," added 30-year-old James, an asylum applicant who fled Uganda after an alleged attempt on his life by his employer. "I was a lawyer in Uganda but look at me here, what am I supposed to do?" asked James, who spoke after emerging from Lunar House but asked not to be named in full for the safety of his family.

Some cases do show there is hope, however. Ikegwu trained as a mechanical engineer and now works at a car-parts outlet. Even Mohammad has taken up campaigning with Detention Action, which he credits with saving him from suicide, as well as female genital mutilation campaigners Straightforward and the Romanian Assembly in his local area. He is determined to help others navigate the system that he found so bewildering.

Lawmakers agree that improvement is needed. Delivering its report last week, the Committee of Public Accounts said the U.K. asylum system requires reform. In addition to the 29,000 people who have waited seven years or more for a decision, the government has admitted it did not know the whereabouts of some 50,000 people whose applications were rejected.

"The Home Office [the government department in charge of immigration] must put in place skilled, incentivized staff and sort out its data so it can crack the backlog and move people through the system," opposition lawmaker and committee chair Margaret Hodge said. "The pressure is on, and the Home Office must take urgent steps to sort out this immigration mess."

The Home Office declined to comment on the issues raised in this story. However, Hodge's comments echoed immigration lawyer Sicher's belief that the immigration system is "broken" and needs more funding.

"As a nation that believes in human rights we should be trying to help these people," Sicher said.