From its outside, The Moore Bar and Lounge — or as it has been affectionately nicknamed by its patrons, Club Langston — may appear like nothing more than an unremarkable hole in the wall. But the club, located on Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, isn’t just any regular old bar. It’s the last black-owned LGBTQ club in New York City, according to its owner, Calvin Clark, who is doggedly fighting to save it.

Clark, 59, opened the bar with his business partner, Eryk Albury, 61, in 2001, and over the last 18 years the venue has become a safe haven for black LGBTQ individuals who’ve had few spaces to call their own. Now, the refuge’s future is being threatened by a combination of rent increases, taxes, business-code violation fees and other miscellaneous costs. Club Langston unofficially closed in late December and may have to close its doors permanently if Clark does not raise $73,000 by March 1.

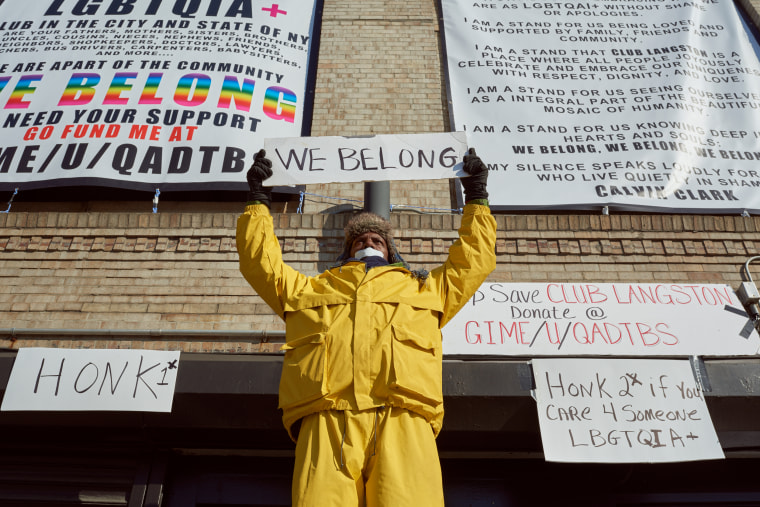

Instead of idly hoping people would contribute to the club’s GoFundMe page, Clark decided to emphasize the significance of the space by taking a vow of silence, fasting and standing in front of Club Langston for 10 days. He began the campaign on Feb. 4 and ended it on Friday morning, after standing outside the club for 24 hours straight.

The signs posted around him explained the reasons for his standing and silence in the unforgiving cold.

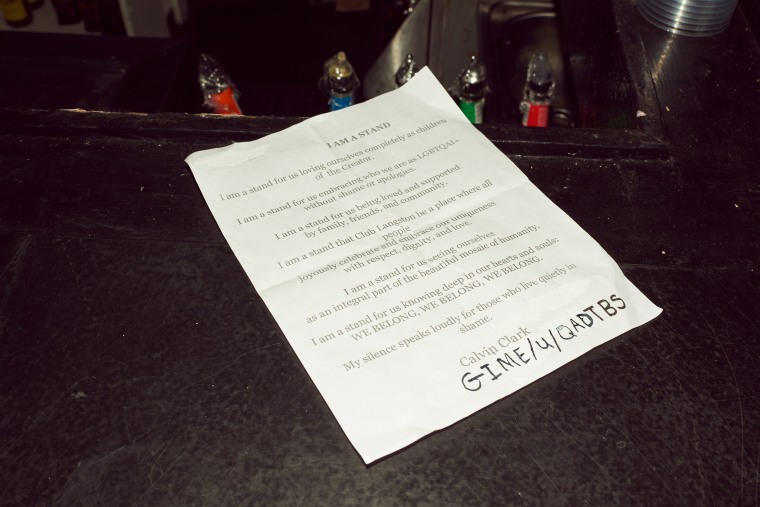

“I am a stand for us embracing who we are as LGBTQAI+ without shame or apologies … I am a stand that Club Langston be a place where all people joyously celebrate and embrace our uniqueness with respect dignity and love … I am a stand for us seeing ourselves as an integral part of the beautiful mosaic of humanity,” one sign reads, in part.

As for why he kept his mouth covered with tape throughout the campaign, the same sign states, “My silence speaks loudly for those who live quietly in shame.”

Though Clark remained silent for the full 10 days, nodding and gesturing with his hands to communicate with passerbys, he had plenty of friends and former club patrons to speak on his behalf.

Gary Newton, who goes by his professional name DJ Smoove, was a DJ at Langston’s for about four years and stayed with Clark during the full campaign. He said that although it’s been less than two months since the club closed, it’s been a difficult loss to cope with, because “there are no other places like it.”

“Most of the clubs in the city don’t really cater to black LGBTQ people,” DJ Smoove, 28, told NBC News. “They put the black people downstairs and play Latin music or EDM, but not hip-hop and R&B.”

Since Club Langston is a black-owned, LGBTQ business, it gave gay black men a place to unapologetically be themselves and enjoy a “safe space,” especially “a lot of black Caribbean people in particular,” said DJ Smoove, who is Jamaican-American. “They can do the things that they like to do that aren’t not acceptable in the city, like how they express themselves dancing. So you’ll see guys spin on their heads and fall to splits.”

Other patrons echoed these sentiments, stating that Club Langston was a place they could go to when they were coming out of the closet and learning more about their sexuality without being judged or threatened.

“Langston’s was our resolve. It was the only place we could go let our hair down,” Trey Writer, 35, said. “It was my first encounter with other gay men; it was my first drink, my first kiss, my first of friendships.”

MORE THAN PARTIES AND CELEBRATIONS

Though Club Langston is known as a hub for parties for Brooklyn Pride, Black Pride, NYC Pride and other major LGBTQ celebrations, it was also a space for community organizing.

Jeffrey Prince, a Club Langston patron and close friend of Clark’s, recalled fundraisers and other events that allowed people to “become politically active through Langston.”

“It was more than just drinking and dancing,” Prince said. “It was a place to discuss the latest political news, see an acquaintance you hadn’t seen in a while. After Hurricane Katrina happened, there was an event … Langston was also very involved in fundraising to address the gay men’s health crisis.”

On certain nights, visitors were even able to get tested for STDs and HIV through Club Langston’s partnership with sexual health organizations, several patrons said.

“People who don’t have anyone to talk to about finding out their HIV-positive talk to Eryke or me,” Clark wrote on a notepad during an interview with NBC News.

Writer noted that because Clark and Albury have been long-time advocates for the LGBTQ community, many people view them as “father figures.” He also said that beyond benefiting members of the community on an individual level, Langston contributed greatly to the safety and the economy of the Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhoods.

“Club Langston’s location alone has provided security to homeward-bound crowds departing the A and C trains late nights knowing that there was a beacon of light, a safe space and people present during times when violence ran amok,” Writer, who regularly attended Club Langston for the last 13 years, said. “The LGBTQ community were protectors and watchmen in their own way.”

MUCH NEEDED RENOVATIONS

Yet, for all the club’s cultural and political significance, it still needs considerable funds to reopen.

DJ Smoove said Club Langston had been struggling for a while, and he remembered one occasion when the ceiling started leaking rainwater. Clark put down a bucket to collect the droplets and people continued dancing, but soon other problems began emerging.

The foremost issue was the heightened gentrification in Brooklyn and the increased rents that accompanied it.

“When Calvin and I moved into Fort Greene in the 1980s, it was nicknamed ‘the black Chelsea,’ because it as a hub for black artists,” Prince said. “But now the gay black community that lives in the Fort Greene, Clinton Hill area is slowly but surely being kicked out.”

Prince said he, too, was priced out of the neighborhood. He recently moved to Queens in order to pay less rent.

Another significant obstacle included costly business-code violations, which Clark took responsibility for in a video describing his standing campaign.

“We need new windows, we need new floors, we need new sound systems, we need new bathrooms,” Clark explained.

Despite the laundry list of renovations, Clark remains positive and said he is looking upon the club’s closing as an “opportunity to increase what we are able to offer the community.”

‘NO DIFFERENT THAN JULIUS OR STONEWALL’

While there’s never a good time for a black-owned LGBTQ business to close, according to Bishop Zachary Jones — one of Calvin’s designated spokesmen during his silence campaign — he said the timing of Club Langston closing down is particularly striking as June is the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising.

“We would love to celebrate our 50th as a unit, as a community and show our presence,” Jones said. “Having our presence there is going to tilt the scale tremendously in terms of the face of gay pride and what that looks like.”

If Club Langston is not able to commemorate Stonewall, Jones fears, it will lead to the erasure of black gay men.

“Homophobia in the African-American community is a still a major problem, gay marriage is still a major problem in our communities, and in the absence of our faces being shown, our participation being present, it’s going to continue that fallacy that within our communities, gay people don’t exist,” Jones said. “It’s going to cripple those who desire to come out and those who desire to live their lives fully.”

Jones and others stress that while businesses unfortunately close down nearly every day, the impact of Club Langston closing will be far-reaching and detrimental.

“The heritage of Langston’s is no different than that of Julius or Stonewall and should be treated no differently,” Writer said, naming two iconic Manhattan gay clubs. “People need to understand you are doing more than just salvaging a nightclub. You are aiding in the survival of a culture.”