Almost a decade after the daily HIV-prevention pill hit the market, long-acting forms of this public health tool, including a drug-infused implant meant to last a year, have shown promise in clinical trials.

Experts believe such medications could launch a new era in HIV prevention, one that is long overdue for Black, Hispanic and younger people, who have been particularly prone to missing doses and dropping out of prevention programs.

Dosed no more frequently than once a month, these new forms of pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, offer potential solutions to a problem that has long frustrated the HIV fight: that many at-risk people find adhering to a daily preventive prescription drug too burdensome.

“I think the long-acting formulations definitely have the potential to improve adherence,” said Elena Bekerman, a senior research scientist at Gilead Sciences. She is on the team investigating lenacapavir — a highly potent antiretroviral that requires an injection only every six months — as HIV prevention.

Gilead manufactures the two antiretrovirals currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for HIV prevention: Truvada and Descovy, which when taken daily reduce men’s risk of contracting the virus from sex with other men by more than 99 percent. For women, Truvada lowers risk by at least 90 percent.

PrEP has helped drive down HIV in cities such as New York and San Francisco. But on a national scale, it has fallen short in slowing the spread of HIV among some high-risk groups.

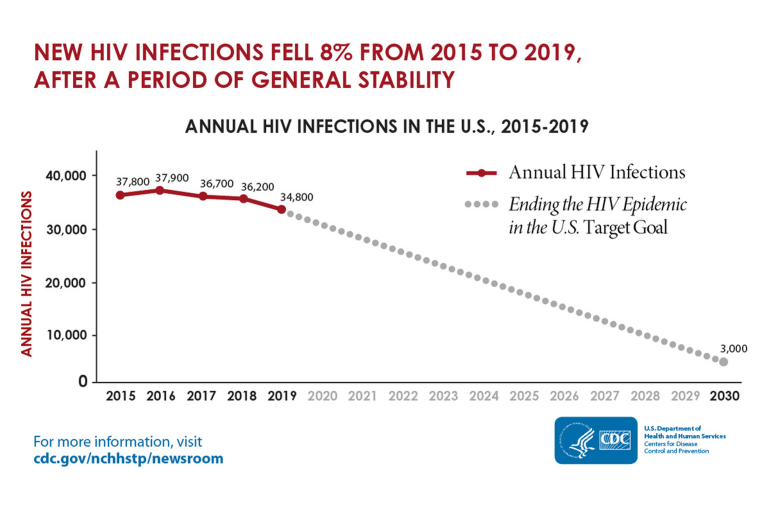

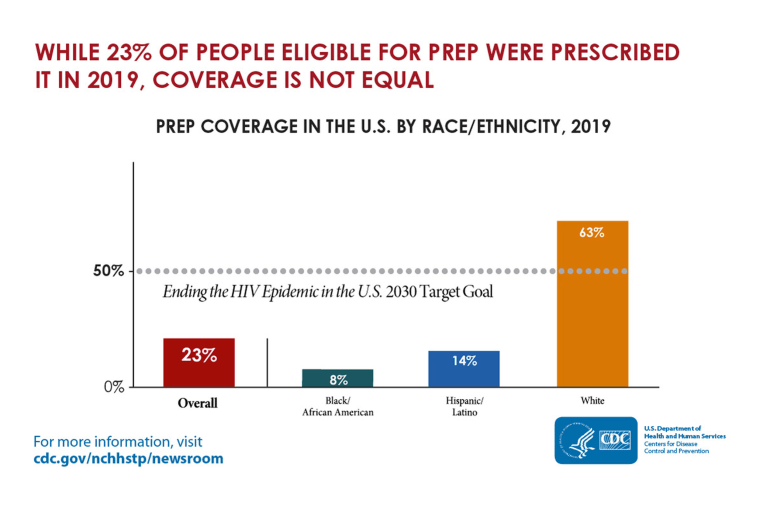

In May, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that following a few years of stagnancy, the nation’s HIV transmission rate declined by only 8 percent, to about 34,800 cases, between 2015 and 2019. The CDC also estimated that white gay and bisexual men make up the vast majority of the 285,000 people believed to be taking PrEP by 2019.

These figures point to an extraordinary failure in promoting PrEP among Hispanic and Black men who have sex with men, among whom nearly half of HIV diagnoses occur.

Dr. Maya Green, a family medicine physician and HIV specialist at Howard Brown Health in Chicago, expressed excitement over the potential for these new forms of PrEP to make an impact among the large population of LGBTQ people of color she treats. “Because anytime you make different options available to communities,” she said, “that usually increases uptake and usage.”

In a pair of large clinical trials of ViiV Healthcare’s cabotegravir, injections given by a health care worker every eight weeks of the long-acting antiretroviral proved even more effective than a prescription for daily Truvada pills at preventing HIV acquisition — 66 percent more so among transgender women and cisgender men who have sex with men, and 89 percent among cisgender women.

Adherence was the key to this difference. Participants in these studies appeared to have a much easier time making it to the clinic every other month than taking their pills every day.

Previous research found that Truvada’s power to prevent sexual transmission of HIV between men drops off steeply if men on PrEP take fewer than four pills per week.

“Traditionally, uptake of PrEP has been low for a number of reasons, such as stigma, including self-stigma, or the perceived burden of daily dosing,” Dr. Kimberly Smith, head of research and development at ViiV, said.

Contracting HIV while adhering poorly to daily PrEP can also give the virus the opportunity to develop resistance to either of the two antiretrovirals contained in Descovy or Truvada, potentially narrowing treatment options. Additionally, cabotegravir can linger in the body for many months after a final dose. This has raised concerns that poor adherence to this regimen might also give rise to resistance, should individuals quit their injections and then contract the virus after the concentration of cabotegravir in the body has dipped below the protective level.

The Food and Drug Administration is slated to issue a decision about cabotegravir’s use as PrEP by early 2022. Gilead’s twice-yearly injectable and a monthly pill from Merck called islatravir could similarly get the green light by 2025.

Cost could be a barrier

Federal agencies recently advised health insurers that nearly all of them are now required to cover daily PrEP with no out-of-pocket expenses, including for the medication and the associated clinic visits and lab tests.

But these measures are not expected to apply by default to any newly approved form of PrEP, including cabotegravir. So, insurers could potentially demand substantial copays or other fees for that injectable medication — provided payers cover a drug that will likely have a much higher list price than the $30 per month that the cheapest generic Truvada costs.

ViiV's recently approved monthly injectable HIV treatment, Cabenuva, which includes cabotegravir plus the drug rilpivirine, costs $3,960 per injection, while brand name Truvada retails for $1,840 and Descovy costs $1,930 per month.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force would need to give cabotegravir a recommendation, as it gave to daily PrEP two years ago, as an intervention with an evidence-based net benefit to ultimately eliminate out-of-pocket costs for cabotegravir. This process could take years.

A pair of large surveys of gay and bisexual men presented last week at the 11th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science found substantial interest in long-acting PrEP, but also worries about the potential associated financial burden, especially among men of color and those who reported riskier sexual behaviors. Plus, many men expressed preference for novel HIV-prevention medications that require dosing even less frequently than every other month. Those men’s wish could very well be granted -- in time.

Giving patients more choice

According to Brad Hare, the HIV clinical director for Kaiser Permanente in San Francisco, “The next generation of PrEP is going to be about individualization,” in which multiple forms of medication-based HIV prevention provide at-risk individuals “the options that work best for them at any given time in their lives.”

Sharon Hillier, a prominent HIV researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, presented interim findings at last week’s conference from a mid-stage PrEP study of islatravir. After participants took six monthly doses of the aspirin-sized pill, they still had concentrations of the drug in their blood that are projected to be protective against the virus even eight weeks later.

Merck recently started recruiting participants for a pair of major trials that will compare islatravir’s efficacy as a monthly form of PrEP to daily doses of Truvada or Descovy. Gilead is launching its own pair of large efficacy trials for lenacapavir as HIV prevention, following promising research in monkeys. Results for both pairs of trials are expected in 2024.

In March, Merck announced promising results from an early human safety trial of an islatravir-infused subdermal implant and its plans to begin a larger, midstage study of the implant as protection against HIV lasting up to 12 months.

Attendees of the recent conference also learned about early development at the University of North Carolina of a removable and biodegradable implant that delivered antiretroviral drugs in mice for up to 180 days.

Additionally, the HIV Vaccine Trials Network is developing cocktails of antibody treatments that investigators hope will eventually prove efficacious as prophylaxis against HIV.

Green of Howard Brown said that adding these myriad prevention options to her armamentarium could aid her determined effort to put her patients in the driver’s seat when it comes to protecting themselves against HIV.

“When a patient is a leader in their choice, in their medical decision-making, the outcomes are always better,” she said.

“I always say that the patient is Batman. We’re Robin.”