By the time I drive into Mazunte, it's nearing the golden hour, and the late-afternoon wash of light beckons me to the sea. For three days now I've been scuttling from one location to the next, exploring the Oaxacan coast and pondering how I will ever, seriously, be able to brave the waters of this perilous part of the Pacific — which impishly touts itself as the Costa Chica, the Little Coast. I throw my knapsack into a beach shack and wander down to the waves.

In truth, the shores of this tiny village have been fine for swimming during the past few months. Only now, as the season slips into the stormy months of fall, has the ocean started to stir again. But at least, I realize as I get tossed about in the surf, there's not a single tourist anywhere along the mile-long bay; just a few fearless Mexican kids (who cast themselves into the swell as if it were their own private wading pool), some fishermen fixing their skiffs, and — wait, what's this?

I glance back at the beach and see that a dozen people have suddenly collected, jostling, pointing. The waves drown out their words, but I can tell there's excitement in the air. With great effort I paddle back to land and find, between them and me, a large turtle waddling along the sand. The crowd, now double in size, moves to let the visitor find space, and peace, to lay her eggs. They know the routine. Yet still more staring and pointing, more waiting and wonder. By the time I'm all dripped dry, the turtle has had enough and, without laying her eggs, has stolen away into the sea. The commotion, it seems, was too much for her.

Let's hope she can get used to it: Word is slowly starting to spread about the lesser-known Pacific Mexico. For years, the 70-mile coastal strip of central Oaxaca — the nexus of the Costa Chica — has been in the shadow of its flashier, noisier neighbors to the north: Acapulco, Puerto Vallarta, and even small-town Zihuatanejo. Beyond the loyal coterie of international surfers and middle-class Mexicans, this seaside stretch between Puerto Escondido and Huatulco is still unknown — despite its spectacular string of beaches and its rich biodiversity (more olive ridley turtles hatch here than anywhere else on earth). I have come looking for a blissed-out Mexican beach dream, and — owing to a confluence of socio-geographical seclusion, government mismanagement, and singular surf breaks — it just may exist.

Or, rather, they may exist. Along with a burgeoning number of the cognoscenti, I am drawn to a handful of coastal towns, each an expression of someone's idea of unspoiled Mexico. My personal favorite is Puerto Escondido — a simpatico enclave that's grown beyond its surfer roots, with no big-brand hotels and no town planning, into one of Mexico's most naturally winsome beach towns. Then, a two-hour drive southeast, is Huatulco, a sprawling resort zone without the crowds. And last, midway between the two — lining the coastal dip in the map that's known as "the belly of the whale" — is a clutch of isolated villages anchored by the boho-chic communities of Mazunte and San Agustinillo (think yoga retreats, turtle tourism and secluded virgin beaches). Simply put: These are a lot of flavors for a little coast.

To realize the dream of Oaxaca's jeweled shoreline, it's worth exploring the reality of its isolated and embattled land. The coast has stayed anonymous because it's hell to reach: The 180-mile road there from the state capital is an eight-hour white-knuckle ride through jungle and mountain (though a daily flight connects the two in 40 minutes). What's worse, recently there were riots in Oaxaca City. What started as an annual teachers' strike for better wages escalated in the summer of 2006 into barricaded protests against the state governor, Ulises Ruiz (who's been accused of diverting millions of dollars toward suspect "public" projects). The police moved in, the violence turned deadly (claiming the life of an American documentarian), and the world media branded the evocative Mexican city a no-go zone.

Oaxaca is still hurting. Since the most recent disturbances, in July 2006, the capital remains a shadow of its former vivacity by day and ghostly quiet by night. The coast, meanwhile, has suffered by association — despite being totally divorced from any of the troubles. "It hit us terribly," says Robin Cleaver, co-owner of Puerto Escondido's most venerated hotel, the Santa Fe. "But the truth is, we've had long cycles of bad luck. Just look at what happened in the '90s." By which he means the Mexican peso crisis of 1994; the Zapatista rebel uprising of the same year, which threw neighboring Chiapas into turmoil, and whose restive image spilled over onto Oaxaca; and 1997's Hurricane Pauline, which slammed dead-on into Puerto Escondido and still ranks among Mexico's deadliest. Add to that the fact that this is the country's second-poorest state (after Chiapas) and you have some idea of why the Costa Chica remains off the radar.

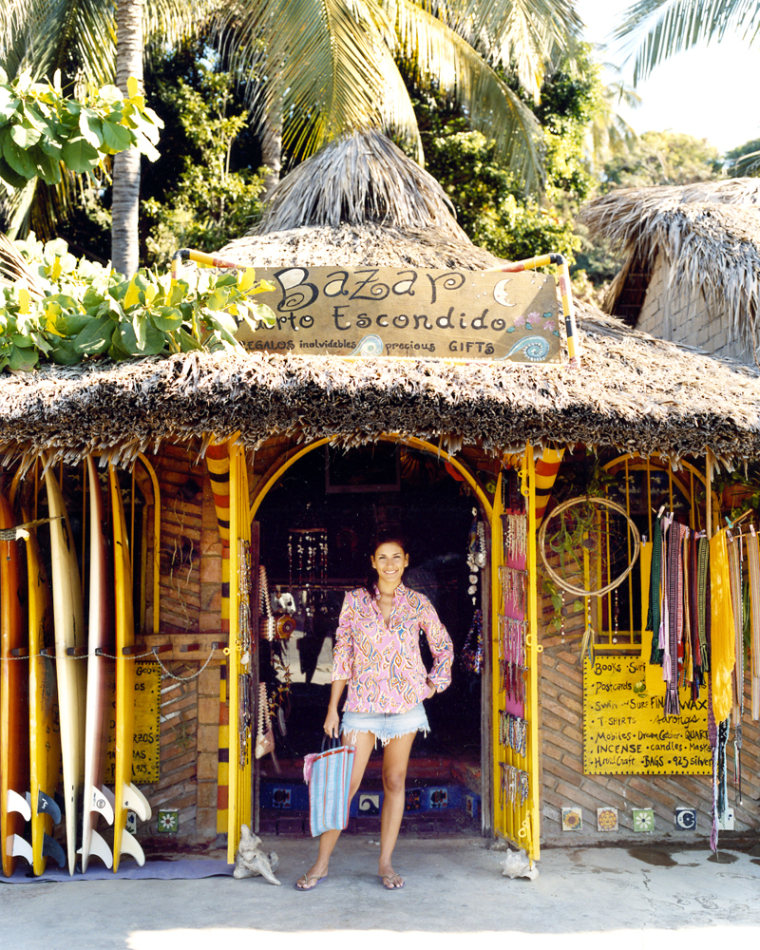

I start my search for the Costa Chica's chilled-out charm in Puerto Escondido — or Puerto, as it's usually called. The first thing that hits you on arrival (at least if you're a man) is that shirt and shoes are optional. Scratch that: Wearing anything above the waist or on your feet is manifestly overdressing. Nobody shakes hands, either. Instead, from Chileans and Australians and Italians (in Puerto, just about everyone's from somewhere else), I receive a sort of surfer-dude salutation that involves a slide and click of the palms followed by a homeboy knuckle bump — and not once do I get it right. I don't even know what questions to ask. On several occasions — at a bar and on the beach — I get to talking and ask: So, what brought you to Puerto? Or, what do you do? The first would invariably evoke an answer involving a vacation gone hippie (came for two weeks, stayed for two years). The second mostly drew a blank gaze and a shrug, as if to say, Like I'd be so bourgeois to actually do anything ...

This is the kind of town that had hippie roots before there were hippies. The first tourist hub on Oaxaca's coastline, the port began to prosper in 1928, exporting the state's famed coffee. By the '40s, it was already dancing to its own tune: When a tax collector came in 1942, he wasn't just kicked out of town — he was killed on the road out. As Gina Machorro, the wondrously provocative veteran of Puerto's tourist booth, puts it, "We have this Oaxacan tradition of being unfriendly to outsiders — or at least to those outsiders who tell us what to do." Which perhaps explains why the federal government never made any headway — as it did, most famously, in Cancún and Los Cabos — with turning this singular piece of paradise into Resortlandia.

Thankfully, Puerto's main beach, Playa Principal, still looks almost exactly as it did half a century ago — a perfect arc of white powder sand fringed by a swath of palms leaning toward the sea. A clutch of palapa huts now skirt the sand, and the fishermen share the waters with teenage bodyboarders. Behind the trees, a pedestrianized downtown drag (or el adoquín, "paving stone") is home to a few decent restaurants, some primitive-looking nightclubs, and Gina Machorro's tourist booth.

"Our beloved governor is trying to rebrand us as the Oaxacan Riviera," Gina tells me on her walking tour of the town. "Even the guidebooks are using the name now. It's insulting. We're the second-poorest state in Mexico, we've got places down the road with no water or electricity, and now we're a Riviera." The Costa Chica is not the Mayan Riviera, nor was it meant to be. Unlike in Playa del Carmen — Mexico's fastest-growing tourist town — development has not spiraled out of control in Puerto: In fact, the town has yet to sprout any five-star resorts, designer hotels or hipster bars. What it does have is a collection of beaches whose drama and diversity are unmatched anywhere in Mexico and whose Playa Zicatela is Latin America's hottest surf destination, bar none.

Half a mile from Playa Principal, Zicatela is where in the 1970s — just as Oaxaca's once-imperious coffee trade was ebbing — Puerto was reborn. Discovered by surfers from San Diego and now known internationally as the Mexican Pipeline, the waves along Zicatela's three-mile stretch break big and barrel into perfect tubes — much like Hawaii's fabled North Shore. So powerful are the waves — which regularly reach 20 feet but have been known to top 60 — that when I first stood on Zicatela's wide golden sands, I felt their vibration: The waves crash with the force of a thunderous storm and rumble your insides. And they don't stop.

"Every day it's like a machine," says Ángel Salinas, Puerto's de facto surf pioneer. "More longboards have been broken here than anywhere else in the world." Ángel should know. A surfer since the age of eight — and famous throughout the surfing world for the colorful wrestler masks he sports at sea — the 41-year-old champion set up the first surf shop in town, as well as Mexico's first surf clinic for children. Puerto now has 15 surf shops in all and holds two international competitions annually, and about a third of the 450,000 visitors who come here annually are "serious surfers," according to Ángel.

"For years, people thought we were just a bunch of bums and weirdos," he tells me at his shop, Central Surf, on Zicatela's sole, seafront street. "It wasn't until 1987, when we had our first international tournament here, that the locals realized, 'Hang on! Everyone's hanging out, enjoying themselves — and they're not drug addicts.' It was, you know, mucha armonía [lots of harmony]. They realized, 'This is Puerto. This is our image.'?" By the '90s, Puerto was barely escondido (hidden) anymore, and nowadays you can find Swiss-made bagels, Japanese sushi, and a Czech-managed hotel on Zicatela — whose laid-back multiculti feel has eclipsed the stale Anytown, Mexico, scene around el adoquín.

Angel's talk of armonía is more than just provincial posturing: Everyone in town wants to be my pal. Midway through our interview, a bleached-blond 20-something walks in (no shoes; though she is, I concede, wearing a bikini top). In an improbable London accent, she introduces herself as Bella, scribbles her e-mail address in my notebook, and walks out. This is not, I assure you, the kind of thing I'm used to — yet it keeps happening. Later that afternoon, a dreadlocked Mexican girl selling necklaces on Playa Principal approaches and asks if I'm from Italy. No, why? "Because I was thinking of trying Italy next year, and I want to know if I need a visa."

Puerto's social kaleidoscope is matched by its changing shoreline. Playa Marinero, I'm told, provides the perfect induction for intermediate surfers and bodyboarders (read: those too awed by the Pipeline). Though truth be told, even Marinero's waves give me too brutal a lashing. Two miles from town, at the foot of a steep, forested cliff, the protected bay of Playa Carrizalillo is more my speed. From my hammock there — on my private terrace at Villas Carrizalillo, Puerto's most beautiful hotel — I feel like I'm floating over an aerial triptych of green, turquoise, and gold.

The Costa Chica's beauty bleeds beyond Puerto. Just inland are the jungled peaks of the Sierra Madre del Sur, home to Oaxaca's resurgent coffee plantations (one of which is now run by the Hotel Santa Fe). And ten minutes west of town is Laguna Manialtepec, a wonderland for birders and kayakers that is separated from the coast by a two-mile-long canal. That's where I'm bound with my half-Swedish, half-Dutch, Mexican-born host Gustavo, known affectionately to his fellow Porteños as Huachinango ("Red Snapper"), because he looks European — as opposed to, say, indigenous, or Afro-Mexican, as is common along Oaxaca's ethnically diverse coast.

We're on wheels: The nightlong downpour has thrown a wrench into our long morning kayak mission, but Gustavo knows I'm up for an adventure, so he hatches an enterprising shortcut on a back road he's never driven. The plan is to reach the canal that connects Manialtepec to the sea and to launch ourselves — without our kayaks — into the water. En route, however, the flooded dirt track grows deeper and bumpier—comically so, as we're tossed about, "Dukes of Hazzard" style.

"This four-by-four must have taken a beating in its time," I tell him as we plow through the knee-deep mud.

"It's not a four-by-four," he replies.

Inevitably, our laughter dies, the pickup gets stuck, and we abandon it. We start walking, sloshing barefoot through hot pools of mud. At the coffee-colored canal, we strip down, jump in, and let the current sweep us toward the Pacific— here freshwater meets salt and a sandbar fractures the open sea. We trade Mexican and British slang, tie our T-shirts turban-style, and bob among the pelicans. I can't remember having this much Huck Finn-type fun since I was in short pants.

For Gustavo, though, the adventure is double-edged. "Not too many people know about this place," he says. "I feel kind of funny publicizing it, although I guess it belongs to everybody."

But what of the more sanitized version of the Costa Chica? I discover it at Huatulco, 70 miles southeast of Puerto. Oaxaca's two seaside hubs may be just a two-hour drive from each other, but they are worlds apart. If Puerto is Oaxaca's magnet for singles, surfers, and budget-conscious venturers, Huatulco draws moneyed Mexican couples seeking their margarita in the sun. Or, if you had to put it in the winkingly pejorative slang favored by Mexico City types, Puerto is for nacos (low-class boneheads) and Huatulco is for fresas (snobs).

Whereas Puerto's ramshackle growth has happened without any federal investment, Mexico's tourism development arm, FONATUR, has so far plunged half a billion dollars into making Hua-tulco another Cancún. Yet the government, try as it might, has been unable to completely desiccate the area's natural beauty. In 1983 (just after the Hotel Santa Fe opened in Puerto), Huatulco set about turning 52,000 acres of virgin beach into a big-box five-star resort. A quarter of a century later, Huatulco's nine golden bays are still serviced by just 2,200 rooms — at best, a tenth of FONATUR's original target, and 500 fewer than Puerto.

FONATUR's loss is nature's gain. A victim of political squabbling, poor planning (unlike in Cancún, there's a bewildering dearth of dining and nightlife), and a lack of state infrastructure (yes, that eight-hour drive from Oaxaca City), Huatulco is now considered the resort that never quite was. Only four of the bays are to be fully built up, with two-thirds of the area left untouched as a "protected zone."

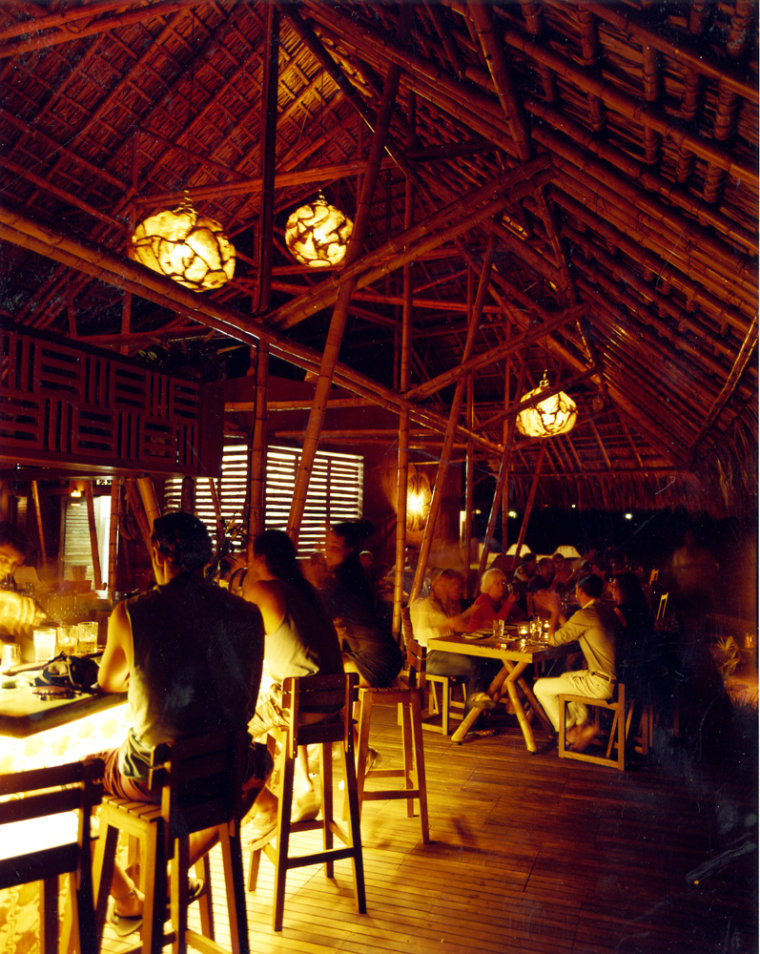

For the most part, I found Huatulco's scale overwhelming. The multi-laned approach to town resembles an airport circuit road; the actual town center, La Crucecita, is three miles from the bayside resorts; and the three developed bays could have been styled anyplace in the world where they sell Sol. Yet there are glittering moments amid the generic dross. The Quinta Real and its spectacular cupola-topped restaurant with full-length windows towers above the cliffs. Sharing Tangolunda Bay was my hotel, the Camino Real Zaashila, whose beachside pool, at a length of 500 feet, had to be the longest I've ever seen.

I sought out Playa Conejos, which I'd heard was Huatulco's one guaranteed spot for fresh-caught local fish — and which is the next (and last) of Huatulco's bays to be developed. Getting there required a ten-minute drive that brought me to an unmarked clearing in a forest right off the highway. I parked the rental car and hiked along a narrow trail that eventually opened onto a beach. Apart from a frolicking couple at the water's edge and a lone palapa shack, the one-mile crescent of golden sand was blissfully unsullied.

The shack turned out to be the fish restaurant: not the sort of place that had menus, or waiters, or bathrooms. A matronly woman emerged and asked if I wanted the catch of the day (sierra fish) served pequeño or grande. It turned out that she, her family, and a small cooperative had run the place — a shack on the sand with no name — for 20 years. I took a seat under the palapa; chomped through the sierra, muy grande and fried whole (outstanding); and asked my host how she felt about making way for the bulldozers.

"¿Qué vas a hacer?" she replied. Her answer was rhetorical: "What are you going to do?"

Huatulco's vacationland is the Oaxaca that FONATUR wants you to see — rather than the rough-and-ready dreamscape of "Y Tu MamÁ También," which was shot along Huatulco's undeveloped beaches. To really experience the small-town magic of Oaxaca's coast, you must head to the belly of the beast, tracing what is nearly the southernmost point of Mexico. There, on the road from Huatulco to Puerto, you'll hit a pearl necklace of villages that includes Puerto Ángel and Zipolite. The former is, from a distance, an exquisite half-moon bay that on closer inspection is ratty and polluted; the latter is a nudist beach where drownings in the riptide are as common as the hard drugs sold there. But then you get to Mazunte, a pretty beach hamlet removed from the madding crowd — and what's more, it's the quiet, delicate epicenter of a marine miracle.

Mexico is home to six of the world's seven sea-turtle species — four of which gravitate to Oaxaca's shores to lay their eggs, and one of which, the olive ridley, now comes in record numbers (150,000 female visits were tracked over three days recently). Until poaching was outlawed in 1990, however, almost the entire community here depended on turtle hunting, with up to 1,000 a day slaughtered (for the utility of their skin and not, as is often mistakenly thought, for the green shell that inspired their name).

Today, Mazunte's former abattoir has been reborn as the Centro Mexicano de la Tortuga, the nation's chief turtle research center and museum. A hundred yards away, the same families who once eked out a living poaching turtles now run a natural-cosmetics cooperative (started in 1999 with a little help from the Body Shop). The two operations turn a tidy and laudable profit in ecotourism, but they're also the area's major letdowns: The museum is in desperate need of imagination, while the cooperative sells creams and oils that are neither of great quality nor, for the most part, locally sourced.

Barely a mile west of Mazunte, however, at Playa Ventanilla, a cooperative of 25 families has proved that sustainable tourism can be a blast. Their central mission is to protect and repopulate turtles and crocodiles — and best of all, you get to canoe through a lagoon that's home to some 800 crocs. My guide, Mateo, leads the exploration with a passion and an intellectual curiosity which suggest that every trip here is an adventure for him — except that he knows every square inch of these mangroved waters.

Without an engine, we're able to get up close and personal with the crocodiles, which can grow to 21 feet in length. Mateo talks about them as if they were family — the biggest he's seen are 13 feet long, the oldest is 35 years old, and so on. About 20 feet away, I spot a sliver of scale emerging, and then a head. "That one," I ask, pointing, "how long is that?"

Without missing a beat, he fires back: "Three point eight two meters. I know because I measured him last November."

Mateo also shows me tropical birds amid the mangroves and deer on an island reserve. The conversation inevitably returns to turtles — which now nest here in the millions, although their survival rates remain alarmingly low. Out of 25,000 eggs, sometimes not a single turtle survives. Despite the hunting ban, turtles are still killed for their meat, skin, and eggs (a delicacy believed to have aphrodisiacal powers), and are openly sold in markets across Oaxaca. The week of my visit, police confiscated 57,000 eggs from a band of turtle smugglers. And every night, La Ventanilla's conservation team scours the beach for eggs so they can relocate them to a protected enclosure before the poachers arrive.

"It's really just a game of cat and mouse," Mateo says. "It all depends on who finds them first.

Turtle tourism has brought visitors and paved the way for low-impact lodgings that embrace the topography. Perched on a steep bluff between Mazunte and neighboring San Agustinillo is Casa Pan de Miel, a five-room designer retreat with an infinity pool hovering over the ocean. Back at sea level, La Posada del Arquitecto is carved right into the rocks on Playa Rinconcito. Its catacomb of rooms feature hanging beds, a shower built into a tree trunk, and thick window shutters — all constructed with wooden nails to counter the oxidizing sea. Like private clubs savoring their anonymity, several hideaways have no road sign, no address, no announcement to the outside world. Rancho Cerro Largo, up a bumpy hill from an unmarked dirt road, is one such lodge, frequented by well-heeled weekenders from Mexico City — even though it has no Web site or phone number.

"We want to keep this secret," says Mario Corella, as we drink a ginger-and-hibiscus tea on his main terrace. One of the first non-locals to build a new life in San Agustinillo, he came here 24 years ago "a blind man without a path." He now presides over a scattering of rustic villas that cascade down the jungled mountainside toward the sea. The largest villa is a yoga studio open to the elements. The cook makes only vegetarian dishes. And the hotel's neighbor is a massage therapist renowned for her techniques rooted in native healing practices.

Cerro Largo is not, as Mario loves to playfully point out, for everyone. "It's dark, there's no running water, you bathe with a gourd cup. There are no pictures on the walls, there are snakes and spiders, scorpions and raccoons, wasps and mosquitoes."

I ask him why people come here.

"For the dream," Mario says.

He doesn't elaborate — he doesn't need to. Like his runaway compadres — and like me (at least for the past ten days) — he's found his dream of another Mexico.