There’s a very good chance your son or daughter will get a credit card as soon as they enter college. You may even encourage them to get one for emergencies or to build up a credit history.

“Credit is something everybody needs,” says Ed Mierzwinski, consumer program director at the U.S. Public Interest Research Group. “But many young people are getting too much credit and are unable to handle it."

According to Nellie Mae, a major provider of student loans, 76 percent of all college undergraduates started the 2004 school year with credit cards. The average outstanding balance on those cards was $2,169.

To a student, “A credit card seems like free money,” says Jim Boyle, president of College Parents of America. “That lure,” he says, “really sucks them into a situation where they’re paying for their purchase many times over because of the interest.”

Mierzwinski, of U.S. PIRG, also worries about the kids who don’t pay off their balance each month. “They’re taking advantage of these kids and getting them into trouble at a young age,” he says.

But the banking industry insists that’s not the case. “College kids are better than the general public at managing credit cards,” says Tracy Mills, a spokesperson for the American Bankers Association. Mills says college students are more likely than the average cardholder to pay their bill in full each month.

Prime targets

Most college students haven’t developed a credit history. They have very little income, if any. And in many cases, they have huge student loans to repay. So why do banks bombard them with credit card offers?

Because students are a prime marketing opportunity. “If they can be in that kid’s wallet, they are more likely to have a customer for a good long time,” explains Geri Detweiler of ultimatecredit.com.

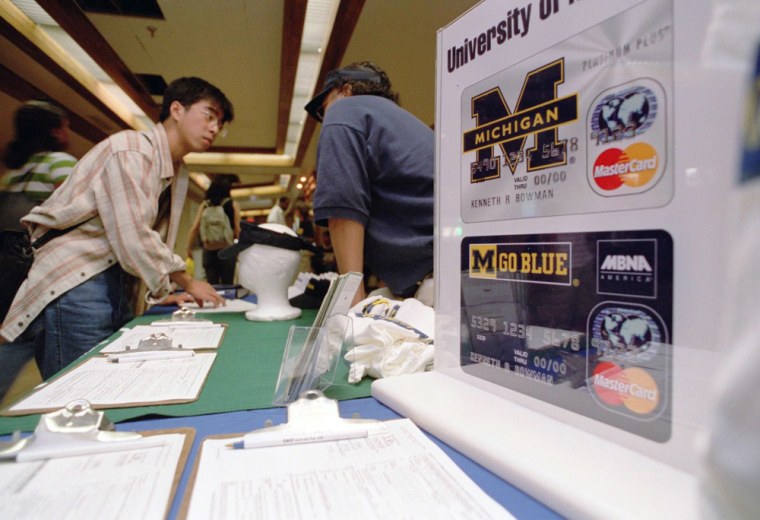

That’s why banks set up kiosks at on campus, offering T-shirts and other goodies to students who apply for a card. By doing this, Mierzwinski says, “banks make getting a credit card an impulse purchase.”

Many colleges and universities get big bucks to help banks market credit cards to their students. James Scurlock, who directed this year’s award-winning documentary “Maxed Out,” says he was “shocked” to learn some schools are paid millions of dollars “to literally hand over their students’ personal information.”

The banking industry likes to remind parents and students that getting a credit card in college can be a good way to start building a credit history. But as Jim Boyle with College Parents of America warns, “If you take out multiple cards and are late on paying, then you are in fact digging yourself a credit hole.”

One student's story

Veronica, a 23-year-old in West Covina, Calif., is living proof of that. She applied for her first card at the beginning of her freshman year. “The offer sounded so good,” she says. “No payments and no interest for two years.” Then she got a letter telling her the interest rate terms were being changed and the interest rate would be 5 percent.

Before the end of her freshman year, Veronica had six cards and a staggering debt of $33,000. She says collection agents would call and tell her to get money from her parents. Veronica refused to do that. Instead she decided to drop out of college and declare bankruptcy.

“Mentally, it took a big toll on me, “she says. “I’m totally different now.” With a bankruptcy on her credit report, she can’t trade in her car or get a cell phone without a huge deposit.

When asked what advice she would give students headed to college, Veronica says, “Just be careful.”

“So many of these kids don’t know how they got into trouble, and they don’t know how to get out of it,” says director James Scurlock. “They are too scared and too ashamed and too humiliated to ask for help because they think they can handle it.”

Student cards are no bargains

Many banks have credit cards specifically designed for college students. They often come with no annual fee, offer rebates or rewards and have an introductory interest rate of zero percent. But once that teaser rate ends — usually after 6 months — the interest will jump to 17 or 18 percent. That’s a lot higher than the average credit card, which carries a rate of 10 to 15 percent depending on type, according to Bankrate.com.

According to a recently released study from the American Council on Education, 25 percent of students with a credit card use it to pay their tuition. These students, the study found, are “more likely than other cardholders to carry a balance from month to month.”

“If they’re not carrying a balance, it’s just a convenience,” says Jacqueline King, director of the ACE Center for Policy Analysis. “If they’re floating their tuition payment, that is an issue, “because there are much less expensive forms of credit. Federal student loans are 6.8 percent vs. the 18 percent that is common on most student credit cards.

Parents need to help

Many young adults don’t realize they can accumulate a huge debt even when they make the minimum payment each month. “One of the things we’re seeing is young people who never intended to abuse credit, but the debt creeps up on them,” says Laura Levine, executive director of the JumpStart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy. That’s why she advises parents to teach their kids how to use credit cards and understand the ramifications of accumulating debt.

Financial experts say parents also need to talk to their kids about making a budget before they head off to school. “Make your expectations very clear,” advises King, “that Mom and Dad are not going to just step in. Tell your child, ‘We’re going to give you this much money every month or every semester, and that’s it.’”