The YouTube party might just be over.

For about a year we have enjoyed the weird and terribly fun video culture it offers. The ease with which people could post, watch, embed and link to videos created a phenomenon that certainly ranks among the top Internet experiences of all time

YouTube was more fun than chat, more creative than Napster, and more energized than just about any Web-based application out there.

YouTube was a rare site that captures so much of what the Web promised to be: a seemingly ungoverned buzzing space that offered glimpses of the strange and familiar. You could catch the hilarious Daily Show segment that spoofed MySpace (and me) or French superstar Zinedine Zidane headbutting his opponent in the World Cup final.

It never came close to fulfilling the heavy promises of the Web: universal knowledge and democratic culture. But it sure was a blast.

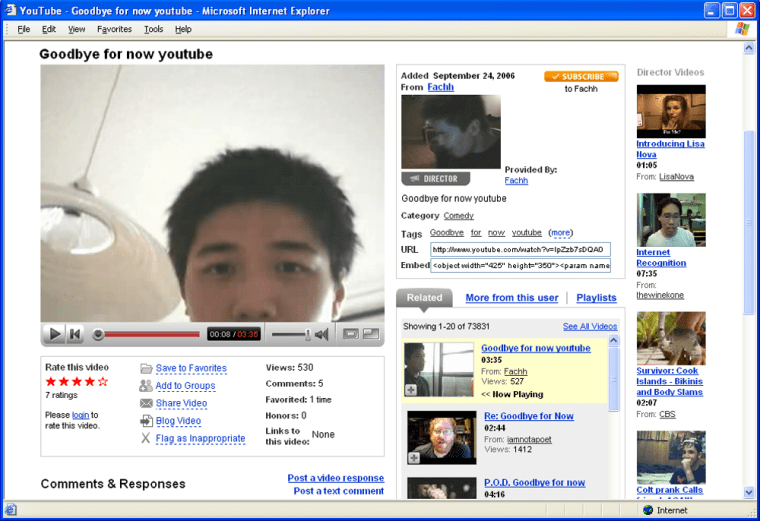

I use the past tense because I suspect that we will look back on the heady days of anything-goes-user-generated content with much nostalgia.

That does not mean that YouTube will change radically over night. Nor does it mean that YouTube will cease to be the major site of user-posted-and-created video clips. It just is unlikely to be quite as noisy and silly.

Already, YouTube aficionados are posting tributes to the cultish video clips that the service seems to be removing at a record pace. Some reports indicate that YouTube removed more than 30,000 clips at the request of a Japanese media group.

It’s not that YouTube now must behave like a grownup company. It’s more that YouTube is becoming the central battlefield in the next great struggle to define the terms and norms of digital communication. So it’s retrenching in preparation for that battle.

And every week that “GooTube” grows in cultural and political importance, the more stories we hear of important video clips coming down.

It’s understandable when YouTube removes a clip after a music or film company sends a “notice-and-takedown letter” to YouTube complaining that a user-posted video contains its copyrighted material and thus possibly infringes. But when the company zap clips simply because of their political content, that’s a different problem.

Here is an example in which copyright acts as an instrument of political censorship: U.S. Rep. Heather Wilson (R-New Mexico) is running for re-election in a close race this fall. Back in the mid-1990s she chaired the New Mexico Department of Children, Youth, and Families.

Problem was, her husband was being investigated about accusations that he had been sexually involved with a minor. So, one of the first things she did as head of the department was remove his file. Now everyone in New Mexico is finding out about it. A blog called Democracy for New Mexico posted on YouTube a news clip of Wilson and others discussing the cover-up.

But New Mexico voters could not view the clip for long: The TV station invoked the "notice and takedown" provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act to kill the video clip.

Of course, any one of my students would be able to tell you at length why posting a news clip of a public official who is under scrutiny and up for re-election would be fair use – an allowable use of copyrighted material for the purpose of news and commentary. But when it comes to the Web, the copyright act has no respect for fair use. Neither does YouTube, apparently. The clip came down.

Here is a more blatantly political example: The radical right-wing columnist Michelle Malkin posted a slideshow video she had spliced together from images of the consequences of violence by Muslim extremists.

For some reason, the editors at YouTube judged it to be “inappropriate.” When Malkin asked YouTube officials to explain the inappropriateness of the video – especially in light of the fact that YouTube is full of clips that seem to glorify violence against American troops, she got no response.

Malkin started a conservative YouTube group to protest the removal, and soon that group was tagged for having “inappropriate” content.

The Malkin saga is troubling and revealing on a number of levels. First, one of the best things about YouTube is that it does use its members to police its content. That means that a virtual community enforces community standards. However, YouTube has no mechanism to debate and work through what those standards should be.

Current YouTube policies make sure that sexually explicit content rarely comes up in a YouTube search. And that’s nice. YouTube is one of the few places on the Web that people don’t get naked on your computer screen.

But such broad policies pretty much invite flame and flag wars, through which competing political activists will flag the other sides’ videos as “inappropriate.” That seems to be happening in the wake of the Malkin controversy.

Now, I have watched Malkin’s video that was removed from YouTube on a competing site. It’s pretty dumb and simplistic. It’s just images of those who have been targeted by violent extremists spliced with some of the controversial Danish cartoons of Mohammed. If the dumb and simplistic were considered “inappropriate” for YouTube, there would be about a dozen videos up there.

In her writing Malkin recklessly associates the deeds of a handful of marginal murderous thugs with the sincere and humane faith of more than a billion followers. She has no problem spreading bigotry. She does that on her blog (to which Google’s Web search links) and her books (which Google offers on Google Book Search).

But that does not mean that this particular video is bigoted. It’s not. But it’s by Malkin. So it’s a target. That’s not a good policy. It’s author-based editing rather than content-based.

The Web should always be the sort of place where you can find troubling and challenging material. It should be the source of stuff too out-there for the mainstream media.

YouTube is not the World Wide Web. And it’s not the government. So it has no obligation to present everything or protect anything. But as it folds itself into the oligopoly known as Google – which increasingly filters the Web for us — we should pressure it to be more inclusive and less sensitive.

So here is my great hope for the Google-YouTube deal: I hope that Google’s boldness and tolerance immediately changes the culture of YouTube. I hope that the YouTube editors grow more confident and less fearful about what they can contribute to the culture of the Web. Meanwhile, it’s up to us to pressure YouTube and Google to keep the Web crazy, fun, and even a little scary.

Siva Vaidhyanathan is an associate professor of Culture and Communication at New York University. His latest book is The Anarchist in the Library: How the Clash Between Freedom and Control is Hacking the Real World and Crashing the System (Basic Books, 2004). Siva blogs at Sivacracy.net.