Paul Mooney is a popular black comedian with a foul mouth who's used a nasty racial epithet as part of his shtick for decades. But when his friend Michael Richards, who's white, spewed that same epithet during a gig at a Los Angeles comedy club, Mooney said it "freaked me out" and "filled me with disgust."

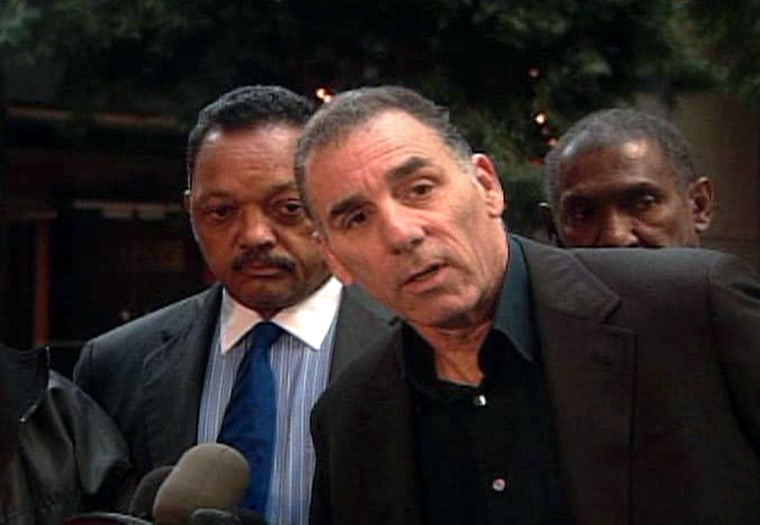

Mooney joined the Rev. Jesse Jackson and Rep. Maxine Waters (D-Calif.) this week in calling for a moratorium by entertainers who use the n-word, the nation's ugliest black pejorative. The proposal, spurred by Richards's racist rant last month, initiated the latest round of a long-standing debate about the term. Black people have fought over the word for years. And nonblack hip-hop and rap music lovers now ask, "If black people can use it, why can't I?"

Mooney said he believes Richards "was trying to channel Lenny Bruce," the edgy comedian who first turned invective into laughs. He was also imitating "Paul Mooney and a bunch of other people," Mooney added in his mea culpa. "He had heard it in rap and all that. I'm part of the problem. I contributed to it, yes."

Randall Kennedy, a black Harvard University professor who authored a controversial book about the word, says he understands its complexity: "It does have a terrible history. It is a word that quite frankly is steeped in blood."

But over centuries, it underwent a sort of Jekyll and Hyde mutation, particularly in black communities. "Like so many words, it does mean different things in different contexts," Kennedy said. "It can be used right now to terrorize and demean people. It can also be used to say you're my man, to show solidarity, to satirize racists and put them down."

‘A romance with the word’

’Which is how Mooney used it in his comedy -- far too much, he said: "I was having a romance with the word, and I was married to it." But now, Mooney said, "I'm free of it. I won't be using that word onstage, and I won't be using the b-word. We're asking the rappers and all the people on Earth to stop using the word."

Reaction has been mixed. Some black people said Mooney's stand is principled and noble. But others, including comedian Dick Gregory, who said he was once Mooney's mentor and will perform with him today at the District's Lincoln Theatre, reacted as if the comic had made another joke. Gregory said he might pledge to continue using the word to poke fun and force Americans to confront the ugly side of race.

That happened in earnest on Nov. 17 when Richards singled out a black patron as a heckler -- wrongly, it turned out -- and launched into a hate-filled tirade, rattling off the word like a machine gun and saying that 50 years ago the man would have been hanging "from a tree." The rant was captured by a cellphone video camera and distributed on the Web.

For some, a signature punchline

Gregory said he was one of the first to use the word onstage, without crossing a line as Richards did at the Laugh Factory. In the 1960s, during the civil rights movement, Gregory joked that when a white restaurant owner shouted to him and other black protesters that "I don't serve [blacks]," he dryly replied: "That's okay, because I don't eat 'em."

The late Richard Pryor, once the most famous black comedian, rode the word to fame in the 1970s with chart-topping albums that crossed over into white culture. Another black comedian, Dave Chappelle, duplicated Pryor's feat by using the word as slapstick and social commentary on his Comedy Central cable show.

Both Pryor and Chappelle backed away from the word. Pryor vowed to stop using it after traveling to Africa and saying he saw no one there who fit the description. Chappelle said his skin crawled when a white youngster casually used the word while praising one of his TV sketches.

The word is so reviled that newspapers, including The Washington Post, often refuse to print it. Television and radio stations censor it with a bleep.

Club bans the word altogether

Jackson said the word should be permanently muted. He called on Americans to not buy the DVD boxed set of the seventh season of "Seinfeld," the hit TV show on which Richards portrayed the character Kramer.

Mooney, who wrote for a number of shows and foulmouthed black humorists, including Redd Foxx, said he will wean himself from the word like an alcoholic. "One person can make a difference," he said. The Laugh Factory, he said, has banned the word.

The word is widely used in black entertainment. Comedian Damon Wayans, star of the syndicated black sitcom "My Wife and Kids," even tried to patent it for a line of clothing this year. That effort failed, as did a dozen or so others before his. "I resent the word," Gregory said. "I think it's the filthiest thing in the history of the planet. But we want to get rid of the word without really talking about it in America. You don't clean it up by denying that it exists."

Mark Anthony Neal, an associate professor of black popular culture at Duke University, said the word should be policed in most media but not deleted from the culture altogether.

"Before we can start telling white people who aren't using the word as a pejorative that you can't use it, we need to be honest about how we've used the words," Neal said.

Richards clearly crossed a line, he said, then added, "How much political capital do we want to use in admonishing Michael Richards? Should we worry about people who call us [that word] or about people who treat us like them."