Engineers on Friday fitted the last major piece into what they say will be the world's largest scientific instrument — a nuclear particle accelerator in a 17-mile (27-kilometer) tunnel under the Swiss-French border.

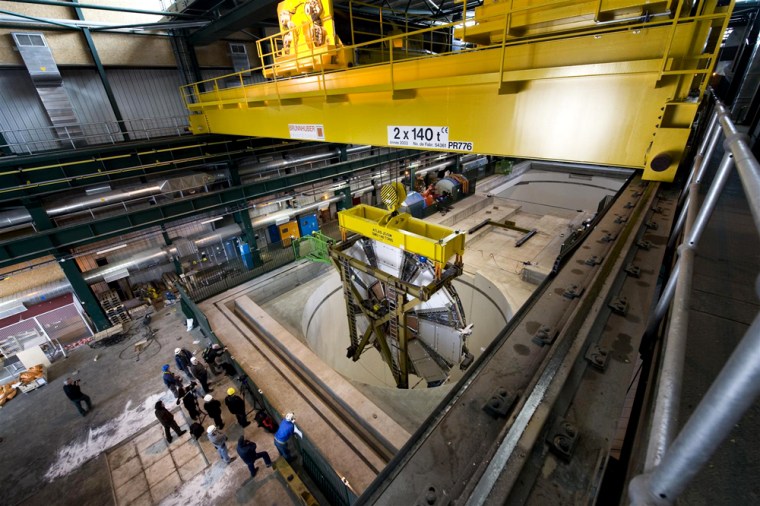

The wheel-shaped piece of equipment, with a diameter of about 30 feet (9 meters), was lowered down a 330-foot (100-meter) shaft and fitted with other equipment known as detectors in an underground room the size of a cathedral.

"It's exciting, but at the same time there is a feeling of relief," Robert Aymar, director-general of the European Organization for Nuclear Research, said as he watched.

The startup date for the Large Hadron Collider, eagerly awaited by scientists planning to use it for studying the makeup of matter and the universe, has not been set. Aymar said the $2 billion project, under construction since 2003, appeared to be on target for completion by this summer.

"For such a huge, complex enterprise, difficulties are there," Aymar, a French scientist, told The Associated Press in an interview at CERN, as the organization is known from its French acronym.

‘Butterflies in my stomach’

The wheel installed Friday contains a cluster of tightly packed detector chambers made up mostly of either copper or aluminum. Their function is to trace the particles that come off protons when they collide at the speed of light.

"When the wheels were shipped from where they were assembled at CERN, I had butterflies in my stomach," said Frank Taylor, a senior research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "In fact, I mentioned to somebody it was valium in the morning and, if successful, champagne in the afternoon. Now I've just gone to coffee."

He said hard work remains for his team, which must connect the rest of the detector to the wheel that was assembled from precision parts made in several countries.

Colder than outer space

When everything is assembled — and some smaller pieces still need to be put in place — scientists will lower the temperature section by section to near absolute zero — colder than outer space.

That will enable them to use superconducting magnets to guide the streams of particles around the tunnel. The plan is to steer packets of particles aimed in opposite directions so that they collide.

The collider is replacing a less-powerful model that was removed from the tunnel in 2000.

The lab's 20 European member countries, as well as observer states like the United States and Japan, contribute to CERN's annual budget of about $940 million.

Thousands of scientists from 80 countries are planning projects on the new collider, which became a main focus for world research into the nature of matter and the origins of the universe after the U.S. Congress in 1993 halted construction on the proposed Superconducting Super Collider in Texas.