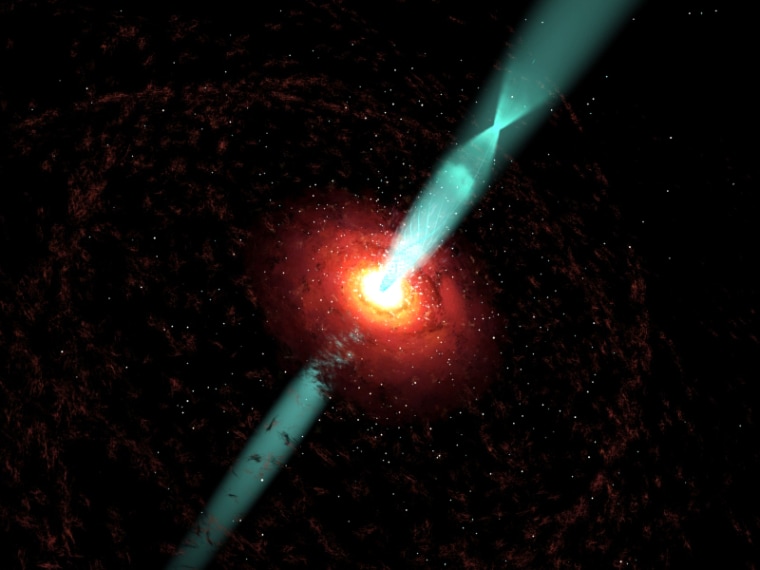

Using powerful radio telescopes, scientists have captured a supermassive black hole just as it was belching out a jet of supercharged particles, offering a first look at how these cosmic jets are formed, they said on Wednesday.

Supermassive black holes form the core of many galaxies and astronomers have long believed they were responsible for ejecting jets of particles at nearly the speed of light.

But just how they did it had remained a mystery.

An international team of researchers led by Alan Marscher of Boston University just got its first peek.

Marscher's team aimed the National Radio Astronomy Observatory's Very Long Baseline Array — a system of 10 radio telescopes — at the galaxy BL Lacertae.

A kind of supermassive black hole known as a blazar was suspected of spewing out a pair of forceful streams of plasma some 950 million light years from Earth.

A light year, the distance light travels in a year, is about 6 trillion miles.

What they saw was a close up of this charged material winding in corkscrew fashion out of the supermassive black hole, behaving just as astronomers had predicted.

"We have gotten the clearest look yet at the innermost portion of the jet, where the particles actually are accelerated," Marscher, whose study appears in the journal Nature, said in a statement.

Slideshow 12 photos

Month in Space: January 2014

"It helps us understand how these objects are able to accelerate particles up to the near velocity of light," said University of Michigan astronomy professor Hugh Aller, who worked on the project.

A black hole is a concentration of mass so dense that little can escape its gravitational pull. Aller said in a telephone interview that as objects fall into the black hole, others get shot out at very high velocities.

But the trick is capturing enough data at the right time to study how this works.

"We never know when these objects will go off. It depends on when the object falls into it," Aller said.

He said the acceleration process is similar to the output of a jet engine. "We think it is focused by a nozzle of sorts and it comes out at us."