At a meeting in his Pentagon office in early 1981, Secretary of the Navy John F. Lehman told Capt. John S. McCain III that he was about to attain his life ambition: selection for admiral.

But Mr. McCain, the son and grandson of revered Navy admirals, was having second thoughts about following his family’s vocation. He had spent the previous four years as the Navy’s liaison to the Senate, sampling life in the world’s most exclusive club as he escorted its members on trips around the globe — sitting with the sultan of Oman on the floor of his desert tent, or smuggling a senator’s private supply of Scotch through Saudi Arabian customs.

He had found a sense of purpose in an apprenticeship to some of the Senate’s fiercest cold warriors. And in Senator John G. Tower, a hawkish Texas Republican, he had found a new mentor, beginning a relationship that many compared to the bond between a father and son.

With Mr. Tower’s encouragement, Mr. McCain declined the prospect of his first admiral’s star to make a run for Congress, saying that he could “do more good there,” Mr. Lehman recalled. But Mr. Lehman knew duty was only part of the reason.

“He just loved it up there,” Mr. Lehman recalled. “Like very few military people, John heard the music up there, and he really wanted to do it.”

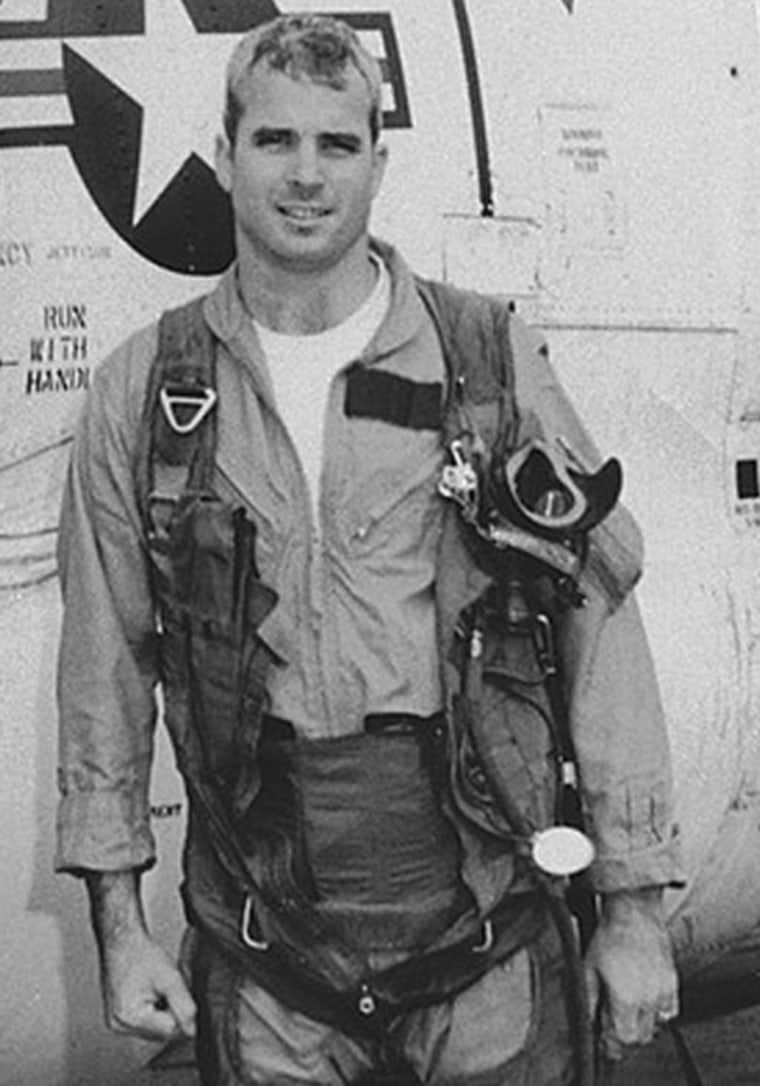

From prisoner of war to politician in a hurry, it was the turning point that started Mr. McCain on the trajectory toward the Republican presidential nomination this year.

After five and a half years of listening to senators’ antiwar speeches over prison camp loudspeakers, Mr. McCain came home in 1973 contemptuous of America’s elected officials, convinced Congress had betrayed the country’s fighting men by hamstringing the war effort. But in the halls of the Senate, he discovered a new calling, at once high-minded and glamorous.

The epitome of cool

One of several Senate military liaisons assigned as advocates for their services and escorts for official travel, Mr. McCain quickly emerged as the senators’ favorite. He had a thick head of hair as white as his dress uniform, and he showed a natural politician’s gift for winning over an audience. He excelled at leavening official business with a spirit of fun — telling deadpan stories about his years “in the cooler,” playing marathon poker games on flights overseas or surprising senators at a refueling stop in Ireland with a side trip to Durty Nelly’s, a 17th century pub.

He was the epitome of cool, one senator’s son recalled, with a pack of Marlboros in one hand and Theodore H. White’s memoir “In Search of History” in the other.

Mr. McCain relished the push-and-pull of legislative battles, eventually even plunging into defense budget fights with a personal agenda that was sometimes at odds with President Jimmy Carter’s secretary of the Navy. He built personal friendships and professional collaborations across ideological divides, a hallmark of his later Senate career. And he applauded the Senate’s leading hawks as they waged what they considered an epic struggle with the Carter administration over America’s place in the post-Vietnam world.

Under Mr. Tower’s tutelage, Mr. McCain turned his anger over the management of the Vietnam War into an all-or-nothing view of international conflict that became one of the few guiding principles in his otherwise unpredictable political career — from his opposition to sending Marine peacekeepers into Lebanon in 1983 to his current staunch support for the Iraq war. And when prominent conservative Christians later protested Mr. Tower’s nomination as defense secretary over accusations of drinking and womanizing, Mr. McCain’s furious counterattack opened the hostilities with that wing of his party that have persisted ever since.

‘Smitten with the celebrity of power’

Mr. McCain has often said he decided to run for office because he felt his war injuries would make attaining the same rank as his father and grandfather “impossible.” But Mr. Lehman, now an adviser to the McCain campaign, and two other top Navy officers familiar with Mr. McCain’s file insist that was not the case.

Instead, many who knew him say, Mr. McCain seemed bored by Navy life. “Sitting down with Anwar Sadat or Deng Xiaoping and being treated as an equal — that is pretty heady stuff,” said Rhett Dawson, a former aide to Mr. Tower who is now president of an electronics trade group. “It had opened his eyes to a much broader world.”

Mr. McCain was captivated, recalled Jeffrey Record, then an aide to former Senator Sam Nunn, the hawkish Georgia Democrat. “He thrives on competition, and he thrives on political combat,” Mr. Record said. “He saw the glamour of it. I think he really got smitten with the celebrity of power.”

First stop in Senate

It is unclear how long Mr. McCain has dreamed of the White House. Languishing in a North Vietnamese prison camp in 1970, he once mused aloud about the presidency, a cellmate, Richard A. Stratton, told a reporter eight years ago.

But when he returned from Vietnam in March 1973, Mr. McCain was so determined to continue as a Navy pilot that in defiance of his doctors he underwent a year of excruciating physical therapy to force an injured knee back to the required range of motion.

A steady trickle of other former P.O.W.’s were running for office, and Mr. McCain’s well-publicized valor as a captive had made him a minor celebrity. But he rebuffed invitations to enter politics, focusing instead on his assignment commanding a fighter squadron near Jacksonville, Fla. He blamed Congress for “willfully breaking America’s word,” he later wrote, which he considered “shameful.”

But Adm. James L. Holloway, the chief of naval operations, saw other uses for Mr. McCain. Mr. Holloway knew that Mr. McCain’s father had once excelled as a Senate liaison. And though the son had earned a reputation as a playboy at the Naval academy, Mr. Holloway thought then-Commander McCain might have inherited the skills and judgment needed to deal with senators.

“He could smoke a cigar and play a little poker,” Mr. Holloway recalled in an interview. “But he didn’t let the situation get out of hand. He could tag along and take care of them and pay the bills and remember where they parked the car. And he was very circumspect. He didn’t get them in trouble.”

Rough waters

Mr. McCain, for his part, was turning 40 and unsure of his path. A shoulder injury still limited his reach, complicating his prospects as a pilot. His marriage to Carol McCain, a former model who was nearly crippled in a car accident while he was imprisoned, was coming apart. He was engaged in a series of extramarital “dalliances,” he later told his biographer, Robert Timberg.

Mr. McCain, in a recent e-mail message, said he was excited about the liaison job. After his release from prison, he wrote, “almost every duty seemed enjoyable.” But some former Senate aides who knew him then say that, at first, he seemed discouraged, stuck at one of several desks in a spartan office. “He looked down and depressed,” recalled William Bader, a former aide to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

But Mr. McCain, promoted to captain, threw himself into courting the lawmakers who shaped Navy policy. He formed especially close friendships with two relative liberals about his age: Senator William S. Cohen, a Maine Republican who represented a major shipbuilding state and later became defense secretary, and Senator Gary Hart, a Colorado Democrat who had managed the antiwar presidential campaign of Senator George McGovern of South Dakota in 1972.

A trip to Asia in late 1978 cemented their bond. Mr. McCain and the two senators stole away from official briefings to stroll in the Ginza district of nightclubs and restaurants in Tokyo, visit the Temple of the Reclining Buddha in Bangkok and take a memorable midnight tour of what Mr. Hart remembered as that city’s “light and dark sides.” In a memoir, Mr. Cohen recalled drinking beer with Mr. McCain at the Hyatt Regency bar overlooking Seoul, watching beautiful Korean women seduce a tipsy traveler.

“He was a salesman par excellence,” Mr. Cohen recalled in an interview, crediting Mr. McCain with redirecting his career by persuading him to join the Armed Services Committee.

The three became regulars together at the Monocle, a watering hole near the Senate. “We would laugh and tell stories about our colleagues,” Mr. Hart recalled. “ ‘So-and-so said something in a caucus meeting.’ He found it fascinating.”

A model for POW-politicians

In turn, Mr. McCain helped Mr. Hart become an officer in the Navy Reserves. For Mr. Cohen, Mr. McCain became a model for the P.O.W.-politician heroes of two novels the Maine senator later wrote. After Mr. McCain met Cindy Lou Hensley at a Honolulu bar on another trip in 1979, Mr. Cohen and Mr. Hart were groomsmen at the couple’s wedding the following year.

Mr. McCain later said that he was inspired to seek public office in part by the example of Senator Henry M. Jackson, Democrat of Washington, the staunch cold warrior who led the defection to the right of the foreign policy thinkers now known as neoconservatives.

“Thank God for Scoop Jackson,” Mr. McCain wrote in his 2002 memoir, “Worth the Fighting For.” “Without his courage, I doubt we would have recovered from Vietnam as quickly as we did, which would have left those who sacrificed there all the more haunted by the futility of the experience.”

The strait-laced “soda-pop Jackson” sometimes brought his school-age children along on official trips, and Mr. McCain played baby sitter. But Mr. Jackson never went in for the kind of camaraderie Mr. McCain enjoyed with Mr. Hart and Mr. Cohen.

In Mr. Tower, however, Mr. McCain found both a social companion and a political mentor. “Tower treated him like a son,” recalled I. N. Kiland, one of Mr. McCain’s colleagues in the liaison office. “And John idolized John Tower.” (Mr. McCain, in his memoir, acknowledged the “familial” comparisons.)

Budding comeraderie

Mr. Tower was a high-living political powerhouse. But he was also a former Navy man who had served under Mr. McCain’s grandfather in World War II and was so sentimental about his service that he stayed in the reserves through his Senate career and packed his uniform for every trip abroad, his aides said.

One of Mr. McCain’s first jobs as liaison was accompanying a delegation Mr. Tower led to the Wehrkunde conference, an annual security meeting in Munich during the Bavarian equivalent of Mardi Gras. The conference became known as kind of senatorial spring break.

The event has grown “a lot tamer” since the late ’70s, recalled Mr. Cohen, who described the heyday of the conference vividly in his novel, “Dragon Fire”: “Beer and passions flowed. All restrictions were off. Grounds for divorce were suspended. Members of Congress, particularly the unmarried ones, would look at the German women, who were ready and willing for the taking, and think they had slipped the surly bonds of moral conformity.”

In Washington, Mr. Tower began summoning Mr. McCain for a drink at the end of the day. And when they traveled, Mr. McCain took charge of supplying Mr. Tower’s hotel rooms with Johnnie Walker Black. One night at a hotel in Saudi Arabia, one of many Middle Eastern countries where alcohol is banned, Mr. McCain amused his patron by leaving empty bottles for the authorities to find outside the room of a group of Frenchmen — a prank Mr. Tower later delighted at recounting.

‘A rapt student’

The Texan also influenced Mr. McCain’s approach to politics. Mr. Tower, who as a graduate student in London had studied the prewar British Conservative Party, saw in President Carter shades of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement, his former aides recalled. As the senior Republican on the Armed Services Committee, Mr. Tower hammered Mr. Carter over the hostages in Iran, support for Taiwan, SALT II and the Soviet invasion in Afghanistan — debates Mr. Tower and other hawks saw as skirmishes in a larger battle over whether America would shrink from confrontation or return to the offensive after Vietnam.

“McCain was a rapt student,” said Mr. Dawson, the former Tower aide. “He followed the debates, and he would take part in them in ways that went way beyond his position as bag-carrier or representative of the Navy.”

Mr. Tower was so close to his protégé that he sometimes raised eyebrows by including Mr. McCain in committee staff meetings that were closed to other military liaisons, Mr. Kiland said. His close ties with Mr. Tower, in turn, helped Mr. McCain earn high marks from his Navy bosses, although with some reservations about his grasp for details.

“Sometimes you had to really explain things to him and put him in a context that he really appreciated,” said former Adm. George Kinnear, Captain McCain’s Pentagon superior. “But he was a hard worker once he bought off on an issue.”

Mr. McCain, with his fame and family, would circumvent the Navy’s chain of command for senators with issues like fighting a base closure, pushing for a new Navy hospital or helping a local contractor, aides said. “McCain had a big Rolodex, we used to say,” recalled Michael Hastings, a former Cohen aide. “He could really deliver for senators on both sides of the aisle.”

Working from the inside out

Over time, Captain McCain also became a minor political player in his own right, sometimes working against the Navy’s official position under the Carter administration. To agitate for laws boosting military pay, former aides said, Mr. McCain steered senators on a trip to Norfolk, Va., toward Navy seamen collecting food stamps. And when the secretary of the Navy declined to replace a giant aircraft carrier, Mr. McCain collected information inside the Navy for lobbyists pushing to build a new one, eventually helping to override a presidential veto.

In his e-mail message, Mr. McCain said he had only been exercising his responsibility to provide senators “the latest and most accurate information.” But former Adm. Clarence A. Hill Jr., then a lobbyist for a new carrier working with Mr. McCain, said: “He was going behind the back of the secretary of the Navy. It is as simple as that.”

A shift into politics

Mr. McCain said in his e-mail message that he had found his Navy job “rewarding and fascinating until my last day of service,” but his former colleagues say that by 1980 they knew he was wrestling with his future.

“There was always this question, ‘Didn’t he want to be an admiral like his father and grandfather?’ ’ Mr. Hastings recalled. “He would say, ‘I don’t think that is what I want to do with the rest of my life.’ ”

Navy psychiatrists offered another explanation. Mr. McCain had long struggled to escape “the shadow of his father,” Dr. P. F. O’Connell wrote in Mr. McCain’s Navy file after his return from Vietnam. But his hero’s homecoming had liberated him, bringing a “smile of fulfillment and relief” when he first heard Admiral McCain introduced as “Commander McCain’s father.” Dr. O’Connell wrote: “He had arrived.”

Finally, in the spring of 1981, Mr. McCain told his father that he was leaving the Navy.

His Senate friends were already moving to jump-start Mr. McCain’s new career. Mr. Cohen connected Mr. McCain with an experienced political consultant, J. Brian Smith, who had initially dismissed working for such a neophyte. And, Mr. Cohen said, he also encouraged Mr. McCain to look away from his previous home in Florida and toward Arizona. His new wife came from a prominent family there, a safe Republican House seat was expected to open up, and Senator Barry Goldwater was expected to retire soon.

Tears for a ‘damn fine sailor’

Mr. Tower did more than anyone else to help. He lent Mr. McCain his fund-raising consultant, raised money for him and enlisted one of Arizona’s most popular Republicans to endorse Mr. McCain over two more experienced primary candidates. “Whatever I asked him for, he gave without hesitation,” Mr. McCain recalled.

He won his House seat in 1982, a year after he left the Navy, and his Senate seat four years later. Mr. Tower retired in 1985, but their paths crossed again when the Texan was nominated to be secretary of defense by President George Bush. The influential Christian conservative organizer Paul M. Weyrich accused Mr. Tower of public drunkenness and philandering, imperiling his confirmation. A chorus of others echoed the charges.

Mr. McCain was stunned at the Senate’s outrage. “There were too many hearty drinkers around the place who might not always have been the most exemplary of devoted spouses to begrudge John his vices,” he wrote in a chapter of his memoirs. “The sins Tower was accused of were hardly Washington novelties.”

Leaping to his mentor’s defense, Mr. McCain denounced Mr. Weyrich as a holier-than-thou hypocrite, scrambled to discredit the charges and exploded in fits of rage at colleagues. At Mr. Tower’s defeat, Mr. McCain choked back tears.

“God bless you, John Tower,” he said from the Senate floor. “You’re a damn fine sailor.”