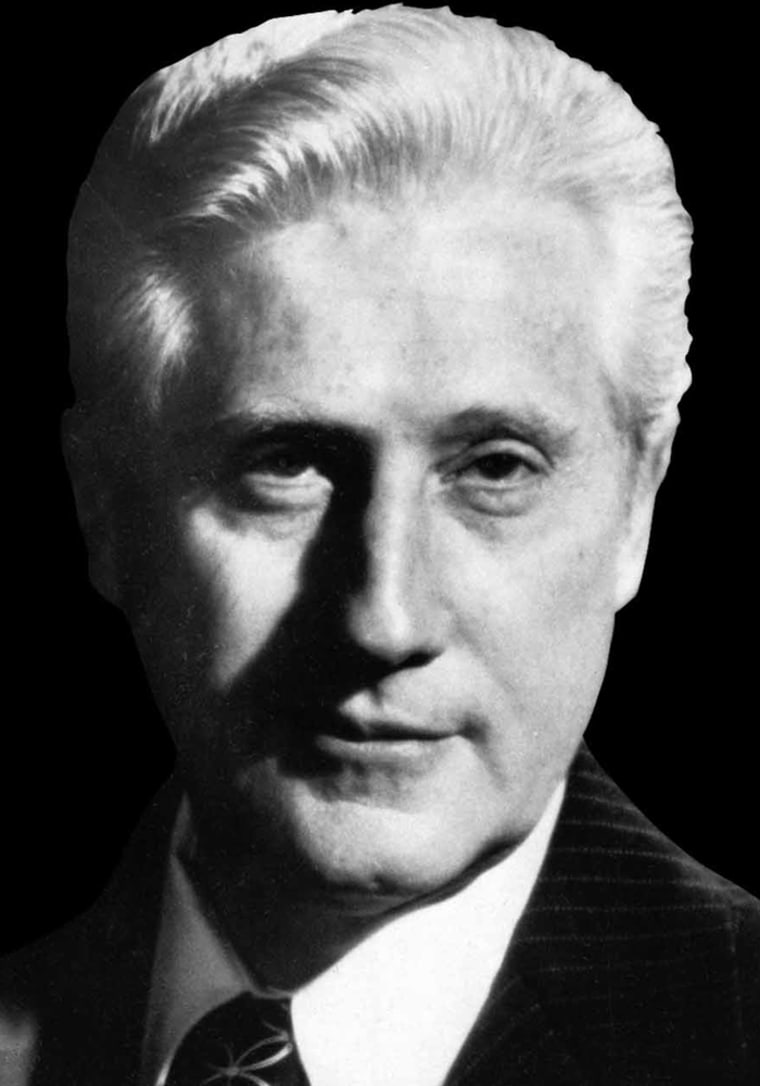

W. Mark Felt, the former FBI second-in-command who revealed himself as "Deep Throat" 30 years after he helped reporters to unravel the Watergate scandal that toppled a president, has died. He was 95.

Felt died Thursday of congestive heart failure in Santa Rosa after several months of failing health, said family friend John D. O'Connor, who wrote the 2005 Vanity Fair article uncovering Felt's secret.

The shadowy central figure in one of the most gripping political dramas of the 20th century, Felt insisted his alter ego be kept secret when he leaked damaging information about Republican President Richard Nixon and his aides to Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward.

The scandal was sparked by the June 1972 break-in at the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in Washington's Watergate complex. That incident and related scandals and cover-ups were eventually traced back to the administration of Nixon, a Republican up for re-election in November 1972. Nixon beat Democrat George McGovern handily, but he resigned two years later in disgrace.

While some — including Nixon and his aides — speculated that Felt was the source who connected the White House to the Watergate break-in, Felt steadfastly denied the accusations until finally coming forward in May 2005.

'I'm the guy'

"I'm the guy they used to call Deep Throat," Felt told O'Connor for the Vanity Fair article, creating a whirlwind of media attention.

Weakened by a stroke, the man who had kept his secret for decades wasn't doing much talking — he merely waved to the media from the front door of his daughter's Santa Rosa home.

Critics, including those who went to prison for the Watergate scandal, called him a traitor for betraying the commander in chief. Supporters hailed him as a hero for blowing the whistle on a corrupt administration trying to cover up attempts to sabotage opponents.

"People will debate for a long time whether I did the right thing by helping Woodward," Felt wrote in his 2006 memoir, "A G-Man's Life: The FBI, `Deep Throat' and the Struggle for Honor in Washington." "The bottom line is that we did get the whole truth out, and isn't that what the FBI is supposed to do?"

Felt's daughter persuaded him to go public to help the family pay some bills, according to the Vanity Fair article.

In a phone interview Friday, Woodward said despite the criticism and Felt's own ambivalence, it is clear that Felt should be remembered as a man who did the right thing.

"This is a man who did his duty to the Constitution," Woodward told The Associated Press.

Just last month, Woodward and onetime reporting partner Carl Bernstein visited Felt in his home. It was the first time Bernstein had met him.

Mystery revealed

The revelation capped a Washington mystery that spanned more than three decades and seven presidents. It was the subject of the best-selling book and hit movie "All the President's Men," which inspired a generation of college students to pursue journalism.

It was by chance that Felt came to play a pivotal role in the drama.

Back in 1970, Woodward struck up a conversation with Felt while both were waiting in a White House hallway. Felt apparently took a liking to the young Woodward, then a Navy courier, and Woodward kept the relationship going, treating Felt as a mentor as he tried to figure out the ways of Washington.

Later, while Woodward and Bernstein relied on various unnamed sources in reporting on Watergate, the man their editor dubbed "Deep Throat" helped to keep them on track and confirm vital information. The Post won a Pulitzer Prize for its Watergate coverage.

The nickname "Deep Throat" was a double entendre: Felt was providing information on the condition of complete anonymity, known as "deep background," and his actions coincided with a popular 1972 porn movie.

Worried that phones were being tapped, Felt arranged clandestine meetings with Woodward worthy of a spy novel. The reporter would move a flower pot with a red flag on his balcony if he needed to meet Felt. The FBI agent would scrawl a time to meet on page 20 of Woodward's copy of The New York Times and they would rendezvous in a suburban Virginia parking garage in the dead of night.

Following the money

In the movie, the enduring image of Deep Throat is of a testy, chain-smoking Hal Holbrook telling Woodward, played by Robert Redford, to "follow the money."

In a memoir published in April 2006, Felt said he saw himself as a "Lone Ranger" who could help derail a White House cover-up. Felt wrote that he was upset by the slow pace of the FBI investigation into the Watergate break-in and believed the press could pressure the administration to cooperate.

"From the start, it was clear that senior administration officials were up to their necks in this mess, and that they would stop at nothing to sabotage our investigation," Felt wrote in "A G-Man's Life: The FBI, 'Deep Throat' and the Struggle for Honor in Washington."

Some critics said that Felt, a J. Edgar Hoover loyalist, was bitter at being passed over when Nixon appointed an FBI outsider and confidante, L. Patrick Gray, to lead the FBI after Hoover's death. Gray was later implicated in Watergate abuses.

"We had no idea of his motivations, and even now some of his motivations are unclear," Bernstein said.

Motivation unclear

Felt wrote that he wasn't motivated by anger. "It is true that I would have welcomed an appointment as FBI director when Hoover died. It is not true that I was jealous of Gray," he wrote.

Ironically, while providing crucial information to the Post, Felt also was assigned to ferret out the newspaper's source. The investigation never went anywhere.

Felt was born in Twin Falls, Idaho, and worked for an Idaho senator during graduate school. After law school at George Washington University he spent a year at the Federal Trade Commission. Felt joined the FBI in 1942 and worked as a Nazi hunter during World War II.

Felt left the FBI in 1973 for the lecture circuit. Five years later he was indicted on charges of authorizing FBI break-ins at homes associated with suspected bombers from the 1960s radical group the Weather Underground. President Ronald Reagan pardoned Felt in 1981 while the case was on appeal — a move applauded by Nixon.

Felt is survived by two children, Joan Felt and Mark Felt Jr., and four grandchildren. His wife, Audrey Felt, died in 1984.