For the 37,000 U.S. troops in South Korea, rising tensions over North Korea’s nuclear programs coincide with outbursts of the most severe anti-American sentiments in the nearly half a century since the end of the Korean War. To the shock of an older generation that vividly recalls the U.S. role in fighting North Korean troops, younger Koreans have displayed rising anger against the U.S. military presence. Last week, as Pyongyang fired off shrill threats, Seoul and Washington struggled to restore confidence in the U.S.-Korean alliance, crucial to regional stability, while GIs faced new threats outside their bases.

In the tawdry bars and billiard halls on legendary “Hooker Hill” in Seoul, the view among GIs is that many Koreans have turned against them, despite their longtime role as protector from aggression by Pyongyang.

“It’s gotten worse, big-time, in the past few months,” said an off-duty Army sergeant, sipping a beer while rap music blared from the speakers and another GI fondled a bar girl in a corner. “I’ve had people talking to me with a hostile attitude. It’s like any time an American does wrong, they want to see American blood.”

In December, in one of the most troubling incidents, three young thugs shouting anti-American obscenities attacked Lt. Col. Steven Boylan, public affairs officer for the 8th U.S. Army, the historic unit that rescued Korea from invasion in the 1950-53 Korean War.

The thugs pinned Boylan to a wall in an underpass and stabbed him repeatedly, but the knife only grazed his stomach as he struck two of the assailants in the head, spun away and ran up the stairs to the nearest base entrance.

The attack on Boylan epitomized the anti-Americanism sweeping South Korea at the time. “We don’t know what to make of it,” said Boylan, back at his desk the day after the incident. “We don’t know if these are isolated incidents or where it’s going.”

“We’ve all come here to do our part for our country,” wrote another U.S. GI based in South Korea who contacted MSNBC.com by e-mail. “Yet our allies here treat us as if we’re the conquering hordes.”

Show of affection

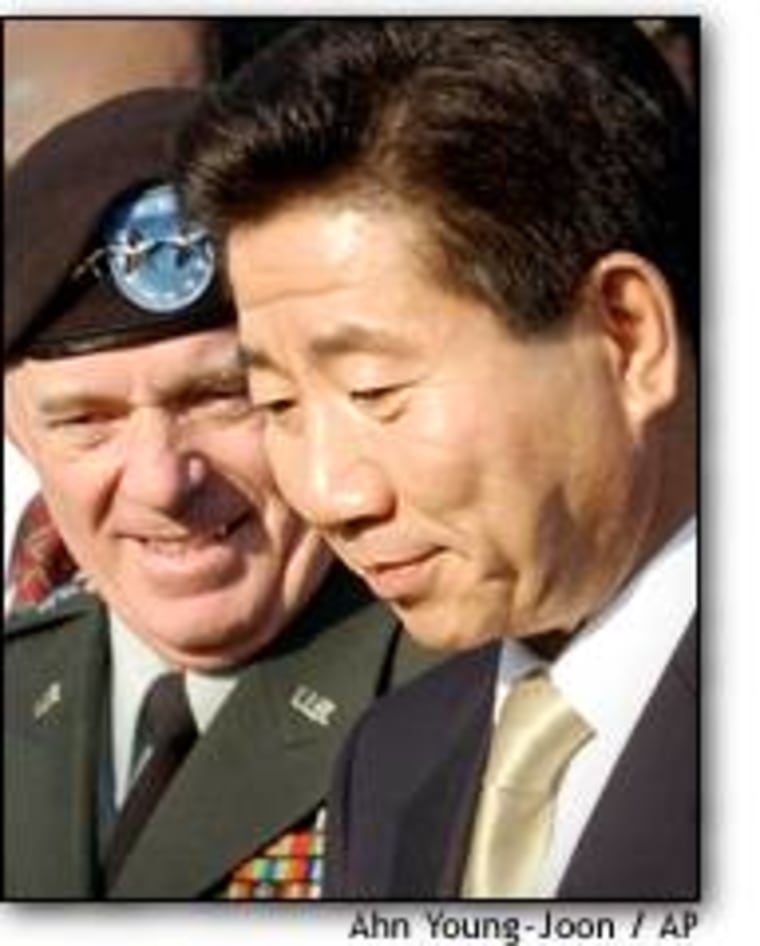

Not far from Hooker Hill, at the headquarters of U.S. forces in Korea, officials from both sides were trying to put a better face on the situation. After a command inspection that began with howitzers booming the traditional 21-gun salute, South Korea’s President-elect Roh Moo-hyun met with the top U.S. commander, Gen. Leon LaPorte, and spoke before a room filled with U.S. and South Korean senior officers.

“Koreans are demanding the alliance improve for better understanding,” said Roh, anxious to prove his moderate stance after having called earlier in his career for withdrawal of U.S. troops from South Korea.

Although Roh took pains to show that he wanted U.S. troops to stay here in the midst of the rising threat posed by North Korean weapons of mass destruction, his words were a tactfully defined reference to demands for revision of the Status of Forces Agreement governing legal relationships between the U.S. military and the host country.

He wanted to signal to the public that he had not abandoned the pledges made during his campaign for “equality” in U.S.-Korean relations.

On Friday, talking to foreign business people, he enlarged on the theme, explaining anti-American protests as having been “staged on the premise that U.S. troops would continue to stay in Korea.” Nonetheless, he observed, there were “voices aspiring for a moer mature relationship between Korea and the United States.”

Mass protest

The controversy over U.S. forces reflects the fallout from one of the worst episodes ever in the U.S.-Korean military alliance. Ever since two Korean schoolgirls were crushed to death beneath the tracks of a 45-ton U.S. armored vehicle June 13, Korean activists have been organizing demonstrations outside U.S. bases, shouting anti-American slogans and, on occasion, tossing Molotov cocktails over the walls.

The campaign, which had shown signs of waning, heated up again in November when a U.S. military court at Camp Casey, a sprawling base about 20 miles from Seoul, acquitted two Army sergeants who had been charged with negligent homicide in the case. Panels of Army officers and sergeants concluded there was insufficient evidence to convict the sergeants, including the driver, whose view was obstructed by his vehicle, and the vehicle commander, who saw the girls but couldn’t reach the driver over the vehicle’s radio link.

Ever since, activists have been staging vigils in which, on occasion, more than 50,000 people have swarmed through central Seoul, holding homemade lanterns made of paper cups and candles, marching on the U.S. Embassy, barricaded by rows of police buses and policemen in Darth Vader anti-riot regalia.

One of the central demands of the demonstrators has been that the United States surrender the two sergeants for trial in a Korean court. More broadly, activists want the Status of Forces Agreement revised so that Korean courts have jurisdiction even in cases in which the suspects were on military operations at the time.

Policy differences

The threat posed by North Korea’s latest moves — withdrawing from key weapons control agreements and treaties and kicking out international monitors of its nuclear program — have done surprisingly little to improve the Seoul-Washington relationship. To supporters of the current and incoming governments in Seoul, the best way to defuse the North Korea threat is to engage Pyongyang, economically and politically, and gradually lure it to reform. President Bush’s hard line on North Korea has undermined that “sunshine policy” and stoked conflict.

Meanwhile, the North Korean government has tried to take advantage of the resentment against Americans in the midst of this crisis by agreeing to hold talks with Seoul and arguing that the two countries — though still technically at war — should team up to counter U.S. domination.

Damage control

Pyongyang’s appeal may not win much sympathy outside a hard-core group of protesters in South Korea.

U.S. officials have promised faster communications with Korean officials and cancellation of operations in which heavy vehicles have jammed the roads. The command has also instituted twice annual “stand downs,” in which all troops stay on base while officers instruct them on issues such as “safety, cultural awareness, consideration of others, prevention of alcohol abuse and dignity and respect toward the Korean people,” according to an 8th Army release.

Roh, who famously said in a television debate at the height of the presidential campaign that he had “no intention of kowtowing to the United States,” seemed to be doing just that in response to an American charm offensive. As part of the offensive, President Bush personally apologized, in a telephone call to outgoing President Kim Dae-jung, for the deaths of the two schoolgirls.

A sign of Roh’s moderating position was that his aides passed the word to the activists that they should scale down their demonstrations, if not halt them altogether, especially since conservatives in the United States were saying, in effect, “If you don’t want us here, we’ll go home.”

A consequence of a precipitous decline in U.S. troop strength, Korean trade officials and business people warned, would be a sharp drop in foreign investment and possibly a boycott by American importers and customers of South Korea’s huge exports of products ranging from motor vehicles to memory chips.

Mood at the crossroads

Meanwhile, U.S. military policemen and Korean national police were on patrol on Hooker Hill, eager to prevent new incidents.

At one of the bars on Hooker Hill, Pvt. Odie Tannelill, an 18-year-old from Fort Worth, Texas, did not seem overly concerned. “It’s not so bad,” said Tannelill, asked what he thought of the demonstrations outside the base.

“Most of us know most Koreans like us here,” said Tannelill. “The only time I noticed anything bad was when the lieutenant colonel was stabbed. They cut off the curfew for a while. We had to stay on base. Now we have to get back by midnight. Of course, we use the buddy system, walking in pairs.”

Outside, Pfc. Al Daniels, 22, from Detroit, said the mood was still tense. “A guy pushed me,” he said. “He said, ‘Screw you, GI.’ He was getting in my face. I pushed him back, and he hit the ground and rolled.” Daniels pointed with a grin to the scene of the incident, outside a snack stand at the base of the hill.

GI’s were resentful, though, that they now pulled extra guard duty because of heightened tensions. “They’re just trying to get their opinion across,” said one of the GIs, requesting anonymity, in between billiard games, “but I wish the Korean public would understand.” He had had to stand so much guard duty, he said, that he never got a Christmas or New Year’s holiday. “They’re hurting the wrong people,” he said.