The Colorado River has left a legacy in the American Southwest as deep as the canyons and ravines it has carved there. The river, by virtue of 14 major dams and dozens of canals, aqueducts and irrigation projects, has powered the development of an entire region of the United States. But even for the mighty Colorado, there are limitations. And according to scientists and planners, the river is a lifeline stretched to the breaking point.

The American Southwest, in its natural state, was mostly desert with scant rainfall. Hot, dry and inhospitable, early explorers saw little potential for settlement. Most were happy simply to get back alive.

But the Colorado River had the power to change that. Its muddy waters twist some 1,400 miles from the mountains of Colorado and Wyoming to the Mexican border and eventually to the Gulf of California. With man’s technological encouragement, its waters have been spread over seven states that are home to 25 million people.

These states -Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, and California - each take a share of the river. Not only does the Colorado provide drinking water, fill pools and water lawns, it also enables cultivation and generates vast amounts of electricity.

The Colorado is the key to the economic miracle that has taken place in the Southwest in this century.

The problem? There is a finite amount of water. As the region continues to grow, new pressures are being placed on the supply. Will there be enough water to go around?

Politics of water

The allocation of the Colorado’s water remains little changed since the Colorado River Compact of 1922. That agreement and various Congressional acts and court decisions that have followed (known collectively as the Law of the River) govern water usage and set the amount each state can take from the river annually and set a minimum flow that is to reach Mexico. In dividing up the river, the states accounted for every drop; no water is “wasted.” The consequence is that there is little predictable excess to be exploited as the region’s water needs grow.

Another problem is that the amounts were set after a period of unusually wet years, making them artificially high.

“Basically, there is no water left after Mexico takes its share,” said Barbara Tellman, a senior research specialist at the University of Arizona’s Water Resources Research Center.

“Given the current laws that govern the river, it is being used to capacity,” said Bob Walsh, the external affairs officer for the Bureau of Reclamation’s Lower Colorado Basin Division. The bureau is the federal agency responsible for managing the river’s use.

The three Lower Basin states - California, Nevada, and Arizona - have exceeded or are nearing their allocations, Walsh said. Nevada is scheduled to use its entire allotment by 2007 and Arizona is already nearing its allowance. California has exceeded its share for many years, and in 1996 was ordered by the Secretary of the Interior to reduce its take.

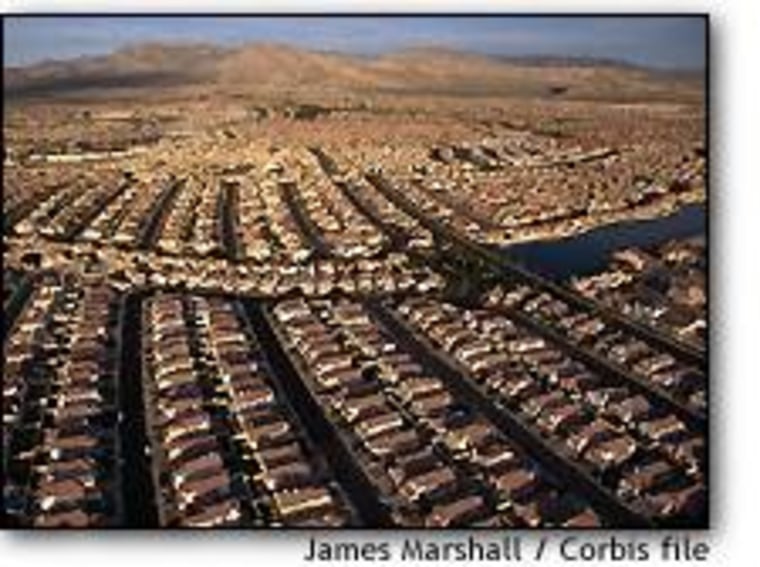

This poses a challenge for states that continue to be home to some of the fastest-growing regions in the U.S. Las Vegas - the fastest-growing city in the nation for much of the 1990s - has already outpaced its water supply and is looking for additional sources. And Southern California expects its water demand to grow 37 percent over the next two decades.

“This is a problem to which most of these places have not yet to awakened, or if they have, they are scrambling to find additional sources of water,” said Kaid Benfield, a senior attorney with the National Resources Defense Council in Washington, D.C.

Changes in usage

In a region that receives on average 4 inches of rain per year, there are few alternative sources to exploit.

One of the key movements shaping up is a transfer of water from agricultural to municipal use. Crop irrigation was a driving factor behind developing the Colorado River, and as water becomes more precious, the competition between urban and agricultural consumption is growing.

However, as Tellman notes, it is not an obvious choice.

“Some say agriculture doesn’t belong in the desert. But you have to look at it in a worldwide perspective,” he said.

As nations around the globe convert farmland into urban space, the rationale for artificially maintaining agricultural production becomes difficult.

Since farmers in the Southwest generally enjoy secure water rights by law, it is not a simple matter to appropriate water from one party to give to another. Any move to alter the mechanism by which farmers historically receive water has been vigorously opposed.

But what politics cannot do, the marketplace often can. Arizona is seeing numerous farms selling out to developers. Dependent on uncertain crop prices and unable to keep up with rising taxes, some farmers have decided it is easier to sell out.

Few farmers fall into this category, but many of the others are discovering that water rights are a valuable asset. In a move no doubt to be seen many times in the future, California’s Imperial Irrigation District recently agreed to sell unused water to the city of San Diego.

Several methods of storing water are being examined as well. In years where the Interior Department declares a surplus beyond the allocations of the Law of the River - which has happened every year since 1996, says Walsh - officials are examining ways to bank the extra water.

One option under consideration is injecting water underground into an aquifer, where it can sit until needed. Arizona, for example, could cede a portion of its share of river water to California in a dry year and pump stored water out of the aquifer.

“There is a lot of belief that the river is not being used to capacity, but the mechanisms to change that do not exist yet,” he said.

Environmental costs

The cost of exploitation has been the natural state of the river. Dammed, diverted, channeled and filled with polluted agricultural runoff, the Colorado is only a shadow of the wild, twisting river it was at the turn of the century. “It’s a series of lakes; it’s not really a river,” says Tellman.

The damage all this has done has led many parts of the country - places with far less concern about water scarcity - to consider removing dams.

Invasive or exotic species are crowding out indigenous ones. Salt cedars have replaced cottonwood trees along the banks, and the elimination of natural habitat has endangered native species of fish.

But the biggest loser might be the Colorado Delta. Mexico uses its allotment of Colorado water much as its neighbor to the north does - irrigating crops in desert conditions. It, too, uses every drop.

As a consequence, the river no longer flows to the Gulf of California. What was once a thriving delta ecosystem now does not receive water from the river in a year of normal runoff. The last time that happened was 1993.

Now fed by agricultural runoff from Arizona and the Mexicali Valley, the delta is poisoned by pesticides and salt and starved for fresh water.

What next?

California, already bumping up against the limits of its water supply and anticipating huge growth in the next 20 years, is beginning to revise its use patterns and conservation practices. But Nevada and Arizona still have water to spare and their growth is fueling string economies. Phoenix, at one point, was expanding at the average rate of two acres per hour.

“The idea of curbing or managing growth has not really caught on,” said Benfield. “That suggests that the Southwest is going to continue to grow in the same manner.”

And all those people will need water.

MSNBC’s Dan McFadden is based in Los Angeles.