It was sometime after midnight on Dec. 8, 2007, when Dr. Eric Goren told me my husband might not live till morning. The kidney cancer that had metastasized almost six years earlier was growing in his lungs. He was in intensive care at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and had begun to spit blood.

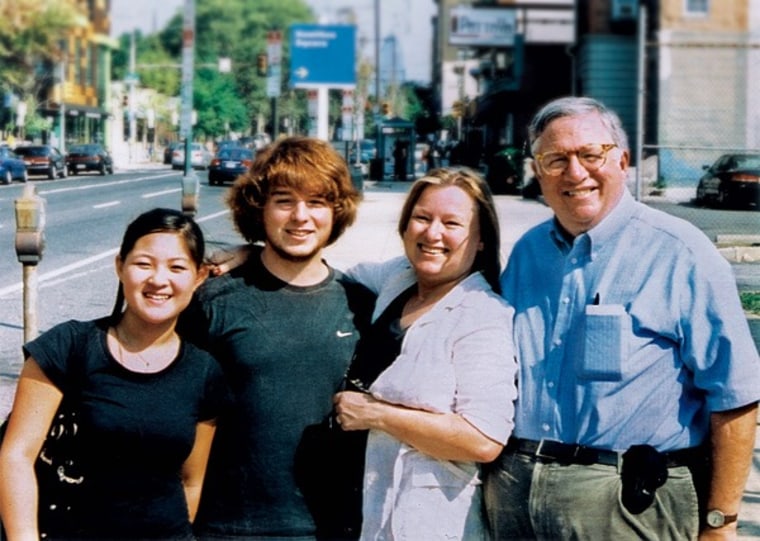

Terence Bryan Foley, 67 years old, my husband of 20 years, father of our two teenagers, a Chinese historian who earned his Ph.D. in his sixties, a man who played more than 15 musical instruments and spoke six languages, a San Francisco cable car conductor and sports photographer, an expert on dairy cattle and swine nutrition, film noir and Dixieland jazz, was confused. He knew his name, but not the year. He wanted a Coke.

Should Terence begin to hemorrhage, the doctor asked, what should he do?

This was our third end-of-life warning in seven years. We had fought off the others, so perhaps we could dodge this one, too. Terence's oncologist and I both believed that a new medicine he had just begun taking, Pfizer's Sutent, would buy him more life.

Keep him alive if you can, I said.

Terence died six days later, on Friday, Dec. 14.

What I couldn't know then was that the thinking behind my request—along with hundreds of decisions we made over the years—was a window on the impossible calculus at the core of today's health-care dilemma. Terence and I were eager to beat his cancer. Backed by robust medical insurance provided by a succession of my corporate employers, we were able to wage a fierce battle. As we made our way through a series of expensive last chances, like the one I asked for that night, we didn't have to think about money, allocation of medical resources, the struggles of roughly 46 million uninsured Americans, or the impact on corporate bottom lines.

Terence's treatment was expensive. The bills for his seven years of medical care totaled $618,616, almost two-thirds of which was for his final 24 months. Still, no one can say for sure if the treatments helped extend his life.

Over the final four days before hospice—two in intensive care, two in a cancer ward—our insurance was billed $43,711 for doctors, medicines, monitors, X-rays, and scans. Two years later the only thing I can see that the money bought for certain was confirmation he was dying. Along with a colleague, Charles Babcock, I spent months poring over almost 5,000 pages of documents collected from six hospitals, four insurers, Medicare, three oncologists, and a surgeon. Those papers tell the story of a system filled with people doing their best. Stepping back and looking at that large stack through a different lens, a string of complex questions emerges.

31 percent for paperwork

Health-care costs represent 17 percent of today's U.S. gross domestic product. Medicare devotes about a quarter of its budget to care in the last year of life, according to the policy journal Health Affairs. Yet as I fought to buy my husband more time, it didn't matter to me that the hospital charged more than 12 times what Medicare then reimbursed for a chest scan. It also didn't matter that UnitedHealthcare reimbursed the hospital for 80 percent of the $3,232 price of a scan, while a few months later our new insurer, Empire BlueCross & BlueShield, paid 24 percent for the same test. And I didn't have time to be thankful that the insurers negotiated the rates with the hospital so neither my employers nor I actually paid the difference between the sticker and discounted prices.

Looking at that stack of documents, it is easy to see why 31 percent of the money spent on health care went to paperwork and administration, according to research published in 2003 in the New England Journal of Medicine. That number has stayed the same or grown since then, says Dr. Steffie Woolhandler, a professor at Harvard Medical School and a co-author of the study. Often Terence's bills, with their blizzard of codes, took days to decipher. What did "opd patins t" or "bal xfr ded" mean? Was the dose charged the same as the dose prescribed?

The documents revealed an economic system in which the sellers don't set the prices and the buyers don't know what they are. Prices bear little relation to demand or how well goods and services work. "No other nation would allow a health system to be run the way we do it. It's completely insane," said Uwe E. Reinhardt, a political economy professor at Princeton University who has advised Congress, the Veterans Administration, and other federal agencies on health-care economics.

In reviewing Terence's records, we found Presbyterian Medical Center in Philadelphia charged UnitedHealthcare $8,120 in 2006 for a 350 mg dose of the drug Avastin, which should have been free as part of a clinical trial. When my Bloomberg colleague inquired, the 80 percent insurance payment was refunded. A small mixup, but telling.

Some drugs Terence took probably did him no good. At least one helped fewer than 10 percent of patients. Today, pharmaceutical companies and government agencies are trying to sort out the economics of developing drugs that will help only a small subset of patients. These drugs are very expensive. Should every patient have the right to them?

Terence and I answered yes. Each drug potentially added life. Yet that, too, led me to a question I still can't answer. When is it time to quit? Congress dodged the question last year as it tried to craft a health-care bill. The mere hint of limiting the ability to choose care created a whirlwind of accusations of "death panels."

One thing I know is that I don't envy the policymakers. As the health-care debate heated up, I remembered the fat sheaf of insurance statements that had piled up after Terence's death. Our children, Terry, 21, and Georgia, 15, assented to my idea of gathering every record to examine what they would show about end-of-life care—its science, emotions, and costs. Terence would have approved.

Taking it all into account, the data showed we had made a bargain that hardly any economist looking solely at the numbers would say made sense.

Why did we do it? I was one big reason. Not me alone, of course. The system has a strong bias toward action. My husband, too, was unusual, said Keith Flaherty, his oncologist, in his passionate willingness to endure discomfort for a chance to see his daughter grow from a child to a young woman, and his son graduate from high school.

After Terence died, Flaherty drew me a picture of a bell curve, showing the range of survival times for people with kidney cancer. Terence was way off in the tail on the right-hand side, an indication he had beaten the odds. For many, an explosion of research and drug discoveries had made it possible to daisy-chain treatments and extend lives for years—enough time to keep our quest from having been total madness.

Terence used to tell a story, almost certainly apocryphal, about his Uncle Bob. Climbing aboard a landing craft before the invasion of Normandy, Bob's sergeant was said to have told the men that by the end of the day, 9 out of 10 of them would be dead. Said Bob: "Each one of us looked around and felt so sorry for those other nine poor sonsabitches."

For me, it was about pushing the bell curve. Knowing there was something to be done, we couldn't not do it. Believing beyond logic that we were going to escape the fate of those other poor sonsabitches.

It is hard to put a price on that kind of hope.

We found the cancer by accident, on Sunday, Nov. 5, 2000, in Portland, Ore. Terry had invited a dozen friends for a sleepover to celebrate his 12th birthday. I was making pancakes and shipping the boys home. Terence had been having stomach cramps for weeks. Suddenly he was lying on the bed, doubled over in pain. Our family doctor ordered him to the emergency room.

We were immediately triaged through. Not a good sign, I thought. The kids sat on the waiting-room floor, Barbies and X-Men around them, while Terence writhed in a curtained alcove.