When Anthony Leto discovered he suffered from a severe heart valve condition, he knew he might not be able to receive care. The 92-year-old New Yorker has a history of heart trouble that labeled him high-risk for the main treatment option: open-heart surgery. Though in his ninth decade, Anthony lives an active lifestyle that includes tending fig trees at his Long Island home. But as his symptoms worsened, his wife Fanny noticed an obvious change in her husband’s behavior.

“He’s either in the garage or working in the yard, he keeps himself busy,” Fanny said. “At the time he wasn’t moving so much.”

Given that about half of all patients who suffer from symptomatic aortic stenosis typically survive less than two years if the condition is left untreated, Leto’s doctors at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, New York began to explore different options, and entered Leto in the Medtronic CoreValve U.S. Pivotal Trial.

Dr. George Petrossian, one of Leto’s doctors and co-principal investigator of the CoreValve trial at the hospital, was blown away by the outcome.

“I’ve never seen anything like this, it’s remarkable,” he said.

Dr. Petrossian, who is also director of interventional cardiovascular procedures, has been in the field over 20 years and finds the CoreValve trial very encouraging for heart patients at Leto’s age. The procedure is less invasive than open-heart surgery, meaning there is an easier recovery for older patients: Leto had his surgery February 2 and spent 7 days in the hospital. Most patients will not even have to stay that long; Leto was a special case since he was the first to receive the implant on Long Island. That’s a big difference from the 10 days in the hospital and weeks of recovery at home patients expect from open-heart surgery.

"Here I am, alive and kicking,” Leto said. He has returned to his normal activities including cooking for his wife on a regular basis. “Sometimes I say the kitchen’s not big enough for two, and she knows that!”

Fanny was also surprised—and relieved—by his quick recovery. “He’s still screaming at me, so I know he’s feeling better,” she joked.

Dr. David Adams, one of two national co-principal investigators for the CoreValve trial, is also amazed at the promising outcomes for older patients. He performed the first CoreValve implantation in the country on 87-year-old Richard Melosh at The Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. (Mount Sinai is one of 40 centers across the country currently taking part in the CoreValve trial, which began in December 2010. Since then, 26 of the 40 sites have started recruiting patients.)

Melosh has a history of heart problems, which includes a heart murmur and multiple operations. In 2010, Dr. Adams scheduled Melosh for open-heart surgery because he developed extremely symptomatic aortic stenosis. During Melosh’s workup, doctors discovered so much calcification that surgery became too risky. As a result, Melosh was entered into the CoreValve trial and received the implant on December 17. Melosh was in the hospital less than a week.

“I had no problems after it,” Melosh said. “None whatsoever. It’s a miracle. I felt no pain, nothing.”

'A major breakthrough'

About 300,000 people worldwide are affected by aortic stenosis; those over 70 are most commonly affected. Aortic stenosis results from calcium depositing around the valve opening, causing the opening to narrow and decreasing blood flow to the heart. When the valve opening becomes about one fourth of its’ original size symptoms develop as the heart starts to weaken. Symptoms include chest pain and breathlessness during exertion.

Dr. Timothy Gardner, medical director of Christiana Care’s Center for Heart & Vascular Health in Newark, Delaware, explained that while aortic valve problems are not as prevalent as other heart issues, it still accounts for about a quarter of his surgeries. Gardner is not taking part in the CoreValve trial, but as a heart surgeon is watching the results very closely.

“This is a major breakthrough in innovation, and provides us with a whole new way of treating this condition in older patients,” Gardner said.

Many older patients who develop aortic valve problems are currently not being treated, cutting years from what otherwise would be a longer life expectancy. “If you don’t treat them, then they are going to be symptomatic and their life span shortened,” said Dr. Newell Robinson, chairman of cardiothoracic and vascular surgery at St. Francis and Petrossian’s co-principal investigator of the trial.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 13 percent of the population is 65 years and older. The Bureau estimates that the older population will be more than twice as large in 2050, growing from 40.2 million to 88.5 million to comprise more than 20 percent of the total population. Robinson hopes if the CoreValve becomes a more widely accessible option, then patients who often turn down or are not recommended treatment because of their age will accept this procedure, allowing them to live a normal life expectancy.

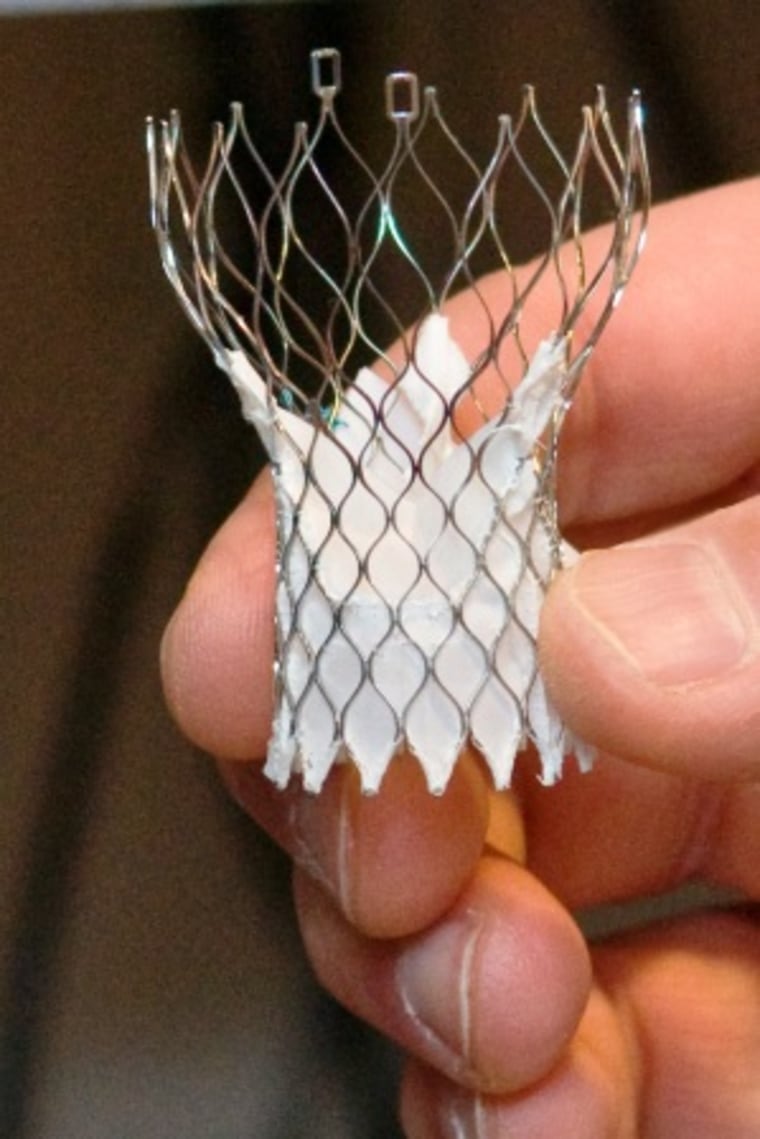

The CoreValve insertion procedure is less invasive than open-heart surgery because there is no need to crack open the patient’s chest, or to put them on a heart and lung machine. Instead, doctors create a small incision in the leg or groin, insert a catheter and move it through the femoral artery and into the heart to deploy the valve, which is made of pig cardiac tissue fixed inside a metal frame.

However, heart patients not taking part in the clinical trial will have a long wait before the valve becomes commercially available in the United States. The CoreValve trial is set to last for 20 months, but Adams, also chairman of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Mount Sinai, says from the start of a trial it takes about three to four years to gather all the information and analyze results before anything is presented to the FDA. Even then, further tests of the device will be required.

One of those tests will be of the device’s long-term durability.

“For the current age group this may not be an issue, they may not have ten or more years left,” Robinson said. “But if we want to use this in a younger age group one day, than durability of five, 10, 15, 20, even 25 years is an issue.”

If the valve is proven safe and effective as it is currently believed it will, Gardner says it “will allow [cardiologists] to treat more patients, more safely” giving surgeons an additional platform for treatment that they have never had before.

While this new procedure is not without its own risks, those risks are outweighed by the possibilities it opens up for the treatment of older heart patients. And it paves a new path of collaboration between heart surgeons and doctors who deal with such cases.

“I think there are going to be a number of positive things that come out of this trial…beyond just what we’re obviously excited about, which is this technology,” Adams said. “[It’s] going to impact medicine beyond the field of cardiovascular therapy.”

While that might be what the future holds, at present Leto is just happy to be back on his feet and able to continue his everyday activities—which includes adding on to his 63 years of marriage with wife Fanny.

“I look forward to more years,” Leto said. “Of complaining, kicking—whatever.”